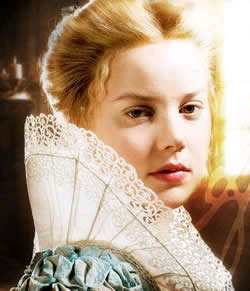

Elizabeth I , "Darnley Portrait", c. 1575

伊丽莎白一世

伊丽莎白一世(ElizabethI,1533年9月7日--1603年3月24日),本名伊丽莎白·都铎,于1558年11月17日至1603年3月24日任英格兰王国和爱尔兰女王,是都铎王朝的第五位也是最后一位君主。她终身未嫁,因被称为“童贞女王”。她即位时不但成功地保持了英格兰的统一,而且在经过近半个世纪的统治后,使英格兰成为欧洲最强大的国家之一。英格兰文化也在此期间达到了一个顶峰,涌现出了诸如莎士比亚、弗朗西斯·培根这样的著名人物。英国在北美的殖民地亦在此期间开始确立。在英国历史上在位时被称为“伊丽莎白时期”,亦称为“黄金时代”。中文名:伊丽莎白·都铎

外文名: Elizabeth Tudor

别名: 童贞女王、荣光女王、英明女王

国籍: 英国

出生地: 普拉森舍宫

出生日期: 1533年(癸巳年)9月7日

逝世日期: 1603年3月24日

职业: 英格兰女王

主要成就: 使英格兰成为最强大的国家之一

开创英国历史的“黄金时代”

皇室: 都铎王朝

在位 : 1558年11月17日—1603年3月24日

伊丽莎白一世[1]伊丽莎白诞生于伦敦的格林尼治普雷森希宫(Greenwich Palace ofPlacentia),名字随她两位祖母,Elizabeth of York 和 ElizabethHoward。她是亨利八世和他的第二个王后安妮·博林唯一幸存的孩子。由于她父母是按新教教规结婚的,天主教认为她是一个私生女。她出生时被指定为王位继承人,她的同父异母的姐姐玛丽成为她的服侍者。伊丽莎白三岁时,她的母亲被判叛逆罪处死,一年后亨利八世和他的第三个王后简·西摩就生了一个男孩:爱德华。伊丽莎白和玛丽都成了爱德华的佣人。当爱德华接受洗礼时,也是伊丽莎白献上他的白色洗礼服(chrisom)。[1]

亨利后来的王后们对这两个公主都很好,亨利本人也经常关注她们的成长,她们受到很好的教育,有可靠的朋友和同龄的伴侣。1547年亨利死后,他最后的王后凯瑟琳·帕尔和她的新丈夫托马斯·西摩(他是简·西摩的兄弟,新国王爱德华六世的舅父)养护伊丽莎白。西摩被年轻的伊丽莎白所吸引,他夫人死后,他本来打算娶她为妇,但他和他的兄弟爱德华·西摩后来都在一系列权利斗争中被处死了。

亨利八世肖像

伊丽莎白受到很好的教育,她的教师包括英国文艺复兴时期著名的人文主义者罗杰·阿斯坎。她受到古典、历史、数学、诗歌和语言的教育。在她统治期间她可以说和写六种语言:英语、法语、意大利语、西班牙语、拉丁语和希腊语。在凯瑟琳·帕尔和她的其他教师的影响下伊丽莎白成为了一个新教徒。

在她弟弟生前,她的地位比较稳定,但爱德华六世(15岁)1553年就因肺结核或砒霜中毒而去世了。她弟弟去世前,曾进行新教的改革,但他的姐姐玛丽却信奉天主教,并可以依仗其父亲遗嘱的力量成功进行宗教改革,所以,他把玛丽从王位继承中除了名,理由是她是个私生女,那么伊丽莎白也不例外,所以爱德华选择了一个信新教的表外甥女——简·格雷(15岁)来接替他。简·格雷夫人只做了九天女王,就被她家翁的同党推翻,并被其后上台的玛丽一世处死。玛丽是一个虔诚的天主教徒,她逼迫伊丽莎白改信天主教。伊丽莎白表面上虽然昄依,但内心仍然是一个新教徒。玛丽对此非常不满。有一小段时间里伊丽莎白甚至被关入伦敦塔。有人认为她是在这里认识了她后来的爱人莱斯特伯爵罗伯特·达德利的,但更可能的是他们在童年时代就相识了(罗伯特·达德利与女王不仅童年相识,两人还是同月同日生,当初伊丽莎白被关进伦敦塔时,罗伯特是为了追随她,与她一起被关进伦敦塔,所以,罗伯特之后被封为莱斯特伯爵也是与这密不可分的)。

伊丽莎白保了命,但玛丽与西班牙王国国王腓力二世的婚礼使得英格兰重归天主教的可能性增大了,对此英格兰人民及贵族都很不满。1558年玛丽无子而亡,伊丽莎白(25岁)成了她的合法继承人。英国国会重申了亨利八世国王规定伊丽莎白作为继承人的安排。

加冕女王

威斯敏斯特教堂

伊丽莎白于1559年1月15日在威斯敏斯特教堂被加冕为女王,当时她的地位很不稳定。她加冕的日子是当时英国著名的数学家和占星士约翰·迪伊挑选的,据说它特别吉利。给她加冕的是卡里斯勒的主教,他是当时在教会界能找到的最高的承认她的合法地位的人。同年她就已经签署了结束意大利战争的卡多-坎陪吉条约。

政治斗争伊丽莎白44年的统治期间英国宗教分歧的斗争非常强烈。1530年代里亨利八世与天主教决裂,英国圣公会建立。爱德华六世的短暂统治期间圣公会的教义日益完善。玛丽统治期间圣公会失去了其统治地位。伊丽莎白恢复了圣公会的地位。在伊丽莎白统治的最初两年间她就发布了至尊法和单一法令,规定国王同时是教会的最高领导人。

虽然她试图在宗教极端派之间寻找一条折衷的路来走,但她本人无疑是一个新教徒。尤其在爱尔兰天主教徒和其他被认为是异教徒的人被迫害。威廉·塞西尔是她政治上最亲密的顾问,为塞西尔她特地创立了柏利勋爵这个爵位。1598年塞西尔死后,他的儿子罗伯特·塞西尔成为伊丽莎白最亲密的顾问,但罗伯特远远不能达到其父亲的能力。她的管理机构中另一个重要人物是弗朗西斯·沃尔辛厄姆爵士。沃尔辛厄姆在整个欧洲建立了一个间谍网。他可以保证所有对女王的阴谋都被他所知。

继承人选

对伊丽莎白最大的批评是她没有提供一个继承人。别人一直以为她会结婚生子,伊丽莎白一世肖像(13张)有许多人追求她,包括她的

前姐夫,西班牙的菲利普国王,以及她的宠臣莱斯特伯爵。许多人认为莱斯特伯爵是她的爱人。伊丽莎白很明智地避免了他们。几年后,当她的统治得到巩固后,人们越来越明显地看到她不会结婚生子了。

当别人质问她为什么她不结婚时,她提到她姐姐统治时期她的处境。当时她不但是玛丽最忌讳的人,而且造反者如托马斯·怀特爵士还利用她的名义。因此她明智地认识到假如她指定一个继承人的话,她的地位会被削弱,而且这一举可以给她的敌人提供一个刺激,因为他们可以利用这个继承人来反对她。但没有继承人英格兰就不会在她逝世的情况下陷入内战。1562年她患天花几乎丧生时这一点变得非常明显。在一段时间里伊丽莎白曾严肃地考虑过结婚生子。但一个天主教的丈夫是显而易见不可能的,而一个新教的丈夫如莱斯特伯爵会立刻加剧宫廷内的宗派斗争。无论她选中谁都不会有好结果。不论她个人的倾向如何,她当时的处境使任何传宗的考虑不能得以实现。

她当时是有一些可能的继承人的,但伊丽莎白对他们都不予考虑。她的表侄女苏格兰女王玛丽·斯图亚特是一个天主教徒。在她从苏格兰王国出逃前,甚至此后她一直是一个非常可能的继承人。玛丽被逐后伊丽莎白虽然接纳了她,但她将玛丽囚禁起来以保障玛丽无法威胁她的地位。玛丽的儿子詹姆士当时还是一个孩子,在他未被考验之前他还不会被考虑到。其他人选也不太可能。伊丽莎白的女伴之一,琴·格蕾的妹妹凯瑟琳·格蕾夫人因为违背伊丽莎白意愿而结婚触怒了伊丽莎白。凯瑟琳·格雷的妹妹玛丽·格雷是一个驮背矮子。伊丽莎白当时一直希望苏格兰的玛丽一世会昄依新教并找一个伊丽莎白认为可靠的丈夫,因此她在玛丽在英格兰被囚期间将她的继承人的问题一推再推。

与此同时她还是继续有结婚的可能性。她曾考虑过在法国的众多王子中找一个丈夫。第一个建议是比她小20岁的奥尔良公爵亨利(后来的亨利三世),当时法王查理九世的弟弟。当这个建议被拒绝后她还考虑过法王更年轻的弟弟阿朗松公爵弗朗索瓦。但弗朗索瓦的早夭使这个计划也破产了。

1568年最后一个有资格做她的继承人的英格兰人,凯瑟琳·格雷夫人,死了。伊丽莎白被迫再次考虑苏格兰女王玛丽。伊丽莎白建议玛丽与莱斯特伯爵结婚,但玛丽拒绝了这个建议。不过这时玛丽的儿子詹姆士已经受到了新教的教育。1570年法王说服伊丽莎白让玛丽重返苏格兰。但伊丽莎白提出了许多苛刻的要求,其中之一就是让詹姆士留在英格兰。虽然如此她的谋士塞西尔还是继续设法帮助玛丽回苏格兰。但苏格兰人拒绝接受这位女王,因此未遂。

宗教宽容

正当此时新教皇庇护五世1570年2月25日革除伊丽莎白的教籍。这使伊丽莎白无法继续她的宗教宽容的政策。同时她的敌人对她的阴谋也使她非常震怒。20年来玛丽一直试图不向伊丽莎白挑战。但这时她陷入了她的天主教同情者的阴谋中。这些阴谋的主谋是安东尼·巴宾顿,其目的是营救玛丽使她取伊丽莎白而代之。对伊丽莎白来说这是一个很好的消除这个大敌人的机会。1587年她处死了玛丽(据说她并不情愿下这条命令)。

相关战争

伊丽莎白向法国的新教徒亨利四世提供了军队和钱财来让他获得法国王位。在八年战争中他向荷兰的新教徒奥伦治亲王威廉一世(沉默者)提供军队来让他反抗西班牙的统治。不但如此,1568年弗朗西斯·德雷克爵士和约翰·霍金斯爵士领导的一支贩奴舰队被西班牙皇家海军重伤后,西班牙的运财舰队不断受到英格兰海盗的劫掠。西班牙国王腓力二世决定以玛丽之死为借口入侵英格兰来击退英格兰对西班牙在欧洲大陆和在其海外殖民地的挑战。

伊丽莎白一世

1588年9月的一场大风暴和伊丽莎白的海军将领们击败了西班牙派出的无敌舰队。虽然如此,西班牙1589年击败了一个更大的英格兰反击舰队。这场战争一直延续到1604年,双方打了个平手,不论在海上还是在陆上英格兰并未能占上风。从1594年起在爱尔兰还爆发了一场游击战。

伊丽莎白最后几年的宠臣是罗伯特·德弗罗,他是莱斯特伯爵的养子。她甚至原谅了他的一些轻罪,但罗伯特1601年参加了一场暴乱,伊丽莎白不得不将他处死。

女王逝世伊丽莎白从未结婚,她的死结束了都铎王朝。在她的晚年,当她不得不确定她的继承人时,她越来越倾向她的侄孙,被她处死的苏格兰玛丽女王的儿子詹姆士。但她从未正式命名他为继承人。1603年3月24日她死于萨里的列治文宫。她被安葬在威斯敏斯特。她的继承人是詹姆士一世。这位詹姆士当时已经成为苏格兰的詹姆士六世了。此时,英格兰和苏格兰同归一个君主,斯图亚特王朝的统治下,开始了不列颠统一进程的第一步──王室联合,但英格兰和苏格兰依然被国际承认为两个国家,而两个国家依然保持自己独立运作的政府。她死50年后,英国资产阶级革命爆发了,英国成为了一个短暂的共和国。

英国文化

伊丽莎白时期是英国文化发展的一个重要时期。文学,尤其是诗歌和话剧进入了一个黄金时代。英国对其他大陆的考察,尤其是对美洲的考察进入了一个新的阶段。如同她的父亲,她本人也从事写作和翻译,她亲自翻译了霍勒斯的《诗歌艺术》。一些她生前的演说和翻译作品一直流传至今。

人物声望

在由BBC主持的民众公选的“最伟大的100名英国人”中,伊丽莎白列前十名。她经常在话剧或小说中出现。1971年格伦达·杰克逊拍摄的《伊丽莎白女王和苏格兰玛丽女王》深受欢迎。1998年凯特·布兰切特在《伊丽莎白》中扮演女王年轻的时候,朱迪·登奇在《莎翁情史》中扮演年老的女王。米兰达·理查森在电视连续剧《黑蝰蛇》中表演了一个超现实主义的女王。同性恋先驱昆汀·克利斯普在《奥兰多》中扮演她。本杰明·布里顿在他为伊丽莎白二世的加冕作的歌剧赞美中描绘了她与罗伯特·德弗罗的关系。

神话传说对后来不列颠的统治者来说伊丽莎白的统治期和当时的许多人物有特别的意义。沃尔特·拉雷格爵士、德雷克和马丁·弗罗比歇爵士成为后来的探险家的原型,威廉·莎士比亚、克里斯多弗·马罗爵士和弗兰西斯·培根爵士成为后代作家的模范。在宗教上伊丽莎白以铁腕统治,但同时相对于她在大陆上的对手来说她给予她的指挥官和顾问们更大的自由。

虽然她有时制定军事行动的战略(比如1589年英格兰对西班牙和葡萄牙的远征),但她从未象亨利五世、奥利弗·克伦威尔或温斯顿·丘吉尔爵士那样亲自充当军事首领。许多军事或探险事业都是舰长的个人决定,皇家许可(尤其是对于海盗行为)都是后来补发的。当时的文学创作更是没有获得皇家的支持。由此可见伊丽莎白时代的许多事件和文化创作实际上是许多个人行动的总和。对后来,尤其是帝国主义时期的英国人来说这是有象征性意义的。丘吉尔曾说过:“她统治时期,和她的臣民与其说是统治关系,倒不如说是情调关系”

现代评价现代欧洲历史学家和传记作者对都铎时代的评价更加写实和客观。从军事上来看伊丽莎白的英格兰并不很成功。虽然西班牙无敌舰队被击败,但这只不过是一场从1585年至1604年持续近20年的战争的开始。英格兰士兵在陆地上(主要在荷兰和法国)的所做所为平平,在1588年后的海战中也是负多胜少。

1589年和1595年至1596年的海军战役尤其损失惨重。1590年至1591年在亚速尔群岛以及1597年英格兰的海盗也遭打击。1595年一支西班牙袭击队在康沃尔登陆并将该郡的大部分地区投入战火。这是历史上很少的几次外国军队在英国登陆的事件之一。更糟糕的是在玛丽一世的最后几年和伊丽莎白的开始五年中英格兰不断被从法国大陆上驱逐。这给英格兰的自尊心给予了很大的打击,而且使英格兰彻底放弃了它在大陆的野心。

伊丽莎白的犹豫不决对军事行动尤其不利。在1589年对西班牙和葡萄牙的远征中英军没有携带围攻炮和火炮。但她的小心谨慎是有原因的,也许它们出于长远的考虑:假如没有一个坚实的战略她不愿英格兰卷入昂贵的、不一定成功的冒险。因此她不愿在对付强大的军队或舰队作战时浪费珍贵的资源。

伊丽莎白时期的英格兰的经济很不稳定。当时英格兰对荷兰和北德意志汉莎联盟的羊毛交易不断增长,这给国家带来了很大的好处。伊丽莎白统治初期接受了玛丽留下的三百万英镑的巨债。伊丽莎白、西塞尔和她的其他官员不得不采取极端手段来限制国家的支出。这些手段有时带来了其他的困难,比如许多士兵(包括抵抗无敌舰队的士兵)很久得不到薪金。但随着国家经济的发展这个情况得到好转。当与西班牙的战争开始时,英格兰的经济盛况是从亨利七世以来从未有过的。

与西班牙的战争给英格兰的经济重新带来了巨大的负担。从1590年代开始英格兰再次负债。尤其爱尔兰的游击战给英格兰的经济带来了巨大损失,它被称为“英格兰国库的漏斗”。伊丽莎白不得不出售国有地面以及官职。1603年英格兰的债务再次达到三百万英镑,与伊丽莎白统治开始时相差不多。不过詹姆士一世后来在和平时期欠债的速度远超过伊丽莎白,而伊丽莎白留下的债务并不是无法控制的。

最近对伊丽莎白统治的批评尤其集中在英格兰的非洲奴隶贸易和她在爱尔兰的失策。这个失策严重地影响了英国和爱尔兰的发展。英格兰是在1562年加入跨大西洋的贩卖奴隶的活动的,当时约翰·霍金斯爵士开始了高利润的偷卖奴隶活动。他从几内亚或其他非洲港口获得他的人类商品,然后将他的俘虏运到西印度群岛的西班牙奴隶市场上出卖。一开始伊丽莎白女王责备霍金斯参加这样不道德的贸易,但当霍金斯向她显示他的事业的利润后她很快就改变了她的见解。她不仅包庇霍金斯的贸易,而且直接从中得利,甚至为他提供船只和人员。伊丽莎白女王对霍金斯的奴隶贩卖的支持为这个贸易提供了皇家的认可,它使这个贸易合法化,它使更多英国商人参加进去了。因此伊丽莎白女王和美国的托玛斯·杰弗逊一样受到批评:尽管她在道义上相信这个贸易是不合法的,但她仍然直接从奴隶买卖中得利。

从亨利二世起英格兰和爱尔兰之间就存在着一个政治联系。但到都铎王朝为止英格兰对爱尔兰的统治是很有限的。都铎王朝开始加强对爱尔兰贵族的统治。亨利八世与天主教断绝后爱尔兰问题就更加加剧了,因为爱尔兰依然是天主教为主的。1568年西班牙成为对手后爱尔兰问题也成为了一个涉及英格兰安全的问题。英格兰驻爱尔兰的官员是臭名昭著的,他们很腐败、对爱尔兰毫不理解,到处树敌。小的起义立刻被镇压。1570年伊丽莎白被开除教籍后对天主教徒的迫害更加加剧,使两个民族的关系更加恶化。1594年,九年战争终于爆发。

这场战争和四个世纪后美国在越南战争的处境相差不多。爱尔兰反抗者使用游击战的手段来消磨和挫败来镇压他们的、装备良好和有训练的英格兰士兵。对英格兰来说,这场战争尤其昂贵。英军受到多次巨大损失。最后英军不得不采用焦土政策,假如有爱尔兰人被怀疑参加反抗,他就全家被杀,英军烧毁田野,破坏农庄,制造了一场空前的人为大饥荒。

1604年詹姆士一世在他的第一个命令中向爱尔兰道歉,才结束了这场战争。但这场战争的残酷性使爱尔兰人对英国人的仇恨、敌对和不信任一直遗传至今。

不过英格兰参加奴隶买卖和对爱尔兰的政策也得按当时的情况来分析看待。虽然伊丽莎白对霍金斯的贸易在道义上予以指责,但她当时面临着三百万英镑的巨债。霍金斯为她提供的经济来源是她所不能拒绝的。不论如何英国在伊丽莎白时期的奴隶贸易远小于西班牙和葡萄牙,也小于后来荷兰在17世纪的奴隶贸易。伊丽莎白对爱尔兰的政策出于她对西班牙的一个“天主教后门”的恐惧。这个问题来自于新教改革在这个国家的失策。它无法简单地解决。当然伊丽莎白和她的官员在爱尔兰的政策无疑加剧了这场冲突,但它还是有战略原因的。

伊丽莎白给她的继承人留下了一个困难的、不稳定的国家。尤其在经济和宗教上许多问题没有解决。她最主要的贡献在于她关心她的臣民,捍卫了她的统治,使用了好的顾问。她的统治帮助英格兰避免了经济上的危机和宗教战争。但17世纪中这场战争还是在拥护查理一世的保皇派和克伦威尔领导的新教徒间爆发了。

注:苏格兰伊丽莎白一世现在的英女皇伊丽莎白二世其实是英格兰的伊丽莎白二世,而苏格兰在此之前并无伊丽莎白一世。所以现在的伊丽莎白二世在苏格兰是伊丽莎白一世,但此前英通过决议:将在全英国称呼伊丽莎白二世为伊丽莎白二世。

影响和评价

伊丽莎白是英国历史上最受欢迎的君主。2002年,在由BBC主持的民众公选的“最伟大的100名英国人”中,伊丽莎白名列第七,超过了英国各地各代所有其他君王。2005年,在历史频道(HistoryChannel)的纪录片《英国最伟大的君主》中,历史学家和评论家们分析了十二位英国君主,并为他们评分(根据六项指数,如军事力量和影响力等,满分为60分),伊丽莎白赢得了最高的48分。她经常在话剧或小说中出现。1971年格伦达·杰克逊拍摄的《伊丽莎白女王》和《苏格兰玛丽女王》深受欢迎。1998年凯特·布兰切特在《伊丽莎白》中扮演女王年轻的时候,茱蒂·丹契在《莎翁情史》中扮演年老的女王。米兰达·理查森在电视连续剧《黑爵士》中表演了一个超现实主义的女王。同性恋先驱昆汀·克利斯普在《奥兰多》中扮演她。本杰明·布里顿在他为伊丽莎白二世的加冕作的歌剧《赞美》中描绘了她与罗伯特·德弗罗的关系。2007年末,电影《伊丽莎白》的续集《伊丽莎白:黄金时代》上映,仍由凯特·布兰切特饰演女王,描述女王登基后的一系列文治武功。

对后来不列颠的统治者来说,伊丽莎白的统治期和当时的许多人物有特别的意义。沃尔特·雷利爵士、德瑞克爵士和马丁·弗罗比歇爵士成为后来的探险家的原型,威廉·莎士比亚、克里斯多弗·马罗爵士和弗兰西斯·培根爵士成为后代作家的模范。在宗教问题上,伊丽莎白虽然以铁腕统治,但同时相对于她在大陆上的对手来说,她给予她的指挥官和顾问们更大的自由。伊丽莎白时期政治的相对开明,也是导致在宣扬“君权神授”的斯图亚特王朝从苏格兰入主后,英格兰各阶层由于强烈反差而开始追求民主自由等价值,并最终引发英国内战和建立世界上第一个民主政权的重要原因之一。

虽然她有时制定军事行动的战略(比如1589年英格兰对西班牙和葡萄牙的远征),但她从未像亨利五世、奥利弗·克伦威尔或温斯顿·丘吉尔爵士那样亲自充当军事首领。许多军事或探险事业都是舰长的个人决定,皇家许可(尤其是对于海盗行为)都是后来补发的,当时的文学创作更是没有获得皇家的支持。由此可见伊丽莎白时代的许多事件和文化创作,实际上是许多个人行动的总和。对后来,尤其是帝国主义时期的英国人来说这是有象征性意义的。

另一方面,不少历史学家也提出了对伊丽莎白时代的批评。一些现代欧洲历史学家和传记作者开始质疑历来对都铎时代的正面评价(例如:Somerset,Guy, Haigh, Ridley,Elton)。从军事上来看,伊丽莎白的英格兰并不很成功。虽然西班牙无敌舰队被击败,但这只不过是一场从1585年至1604年持续近20年的战争的开始。英格兰士兵在陆地上(主要在荷兰和法国)的所做所为平平,在1588年后的海战中也是负多胜少,1589年和1595年至1596年的海军战役尤其损失惨重,1590年至1591年在亚速尔群岛以及1597年英格兰的海盗也遭打击。1595年一支西班牙袭击队在康沃尔登陆,并将该郡的大部分地区投入战火,这是历史上少数次外国军队在英国登陆的事件之一。更糟糕的是在玛丽一世的最后几年和伊丽莎白的开始五年中,英格兰不断被法国从欧洲大陆上驱逐,这给英格兰的自尊心给予了很大的打击,而且使英格兰彻底放弃了它在大陆的野心。

伊丽莎白的犹疑不决,对军事行动尤其不利。在1589年对西班牙和葡萄牙的远征中,英军没有携带围攻炮和火炮。但她的小心谨慎是有原因的,也许它们出于长远的考虑:假如没有一个坚实的战略,她不愿英格兰卷入昂贵的、不一定成功的冒险,因此她不愿在对付强大的军队或舰队作战时浪费珍贵的资源。

伊丽莎白时期的英格兰经济很不稳定。当时英格兰对荷兰和北德汉莎联盟的羊毛交易不断增长,这给国家带来了很大的好处。伊丽莎白统治初期接受了玛丽留下的三百万英镑的巨债,伊丽莎白、西塞尔和她的其他官员不得不采取极端手段来限制国家的支出,这些手段有时带来了其他的困难,比如许多士兵(包括抵抗无敌舰队的士兵)很久得不到薪金,但随着国家经济的发展,这个情况得到好转。当与西班牙的战争开始时,英格兰的经济盛况是从亨利七世以来从未有过的。

与西班牙的战争给英格兰的经济重新带来了巨大的负担。从1590年代开始英格兰再次负债。尤其爱尔兰的游击战给英格兰的经济带来了巨大损失,它被称为“英格兰国库的漏斗”。伊丽莎白不得不出售国有地面以及官职。1603年英格兰的债务再次达到三百万英镑,与伊丽莎白统治开始时相差不多。不过詹姆士一世后来在和平时期欠债的速度远超过伊丽莎白,而伊丽莎白留下的债务并不是无法控制的。

最近对伊丽莎白统治的批评,尤其集中在英格兰的非洲奴隶贩卖活动和她在爱尔兰的失策,这个失策严重地影响了英国和爱尔兰的发展。英格兰是在1562年加入跨大西洋的贩卖奴隶的活动的,当时约翰·霍金斯爵士开始了高利润的偷卖奴隶活动,他从几内亚或其他非洲港口获得他的人类商品,然后将他的俘虏运到西印度的西班牙奴隶市场上出卖。一开始伊丽莎白女王责备霍金斯参加这样不道德的贸易,但当霍金斯向她显示他的事业的利润后,她很快就改变了她的见解,她不仅包庇霍金斯的贸易,而且直接从中得利,甚至为他提供船只和人员。

伊丽莎白女王对霍金斯的奴隶贩卖的支持,为这个贸易提供了皇家的认可,它使这个贸易合法化,它使更多英国商人参加进去了。因此伊丽莎白女王和美国的托马斯·杰斐逊一样受到批评:尽管她在道义上相信这个贸易是不合法的,但她仍然直接从奴隶买卖中得利。

从亨利二世起英格兰和爱尔兰之间就存在着一个政治联系。但到都铎王朝为止,英格兰对爱尔兰的统治是很有限的。都铎王朝开始加强对爱尔兰贵族的统治,亨利八世与天主教断绝后爱尔兰问题就更加加剧了,因为爱尔兰依然是天主教为主的。1568年西班牙成为对手后,爱尔兰问题也成为了一个涉及英格兰安全的问题。英格兰驻爱尔兰的官员是臭名昭著的,他们很腐败,对爱尔兰毫不理解,到处树敌,小的起义立刻被镇压。1570年,伊丽莎白被开除教籍后,对天主教徒的迫害更加加剧,使两个民族的关系更加恶化。1594年开始九年战争终于爆发。

这场战争和四个世纪后美国在越南战争的处境相差不多。爱尔兰反抗者使用游击战的手段来消磨和挫败来镇压他们的、装备良好和有训练的英格兰士兵。对英格兰来说,这场战争尤其昂贵,英军受到多次巨大损失,最后英军不得不采用焦土政策;假如有爱尔兰人被怀疑参加反抗,他就全家被杀,英军烧毁田野,破坏农庄,制造了一场空前的人为大饥荒。

1604年,詹姆士一世在他的第一个命令中向爱尔兰道歉,才结束了这场战争。但这场战争的残酷性使爱尔兰人对英国人的仇恨、敌对和不信任一直遗传至今。

不过,英格兰参加奴隶买卖和对爱尔兰的政策也得按当时的情况来分析看待。虽然伊丽莎白对霍金斯的贸易在道义上予以指责,但她当时面临着三百万英镑的巨债,霍金斯为她提供的经济来源是她所不能拒绝的。不论如何,英国在伊丽莎白时期的奴隶贸易远小于西班牙和葡萄牙,也小于后来荷兰在17世纪的奴隶贸易。

伊丽莎白对爱尔兰的政策出于她对西班牙的一个“天主教后门”的恐惧,这个问题来自于新教改革在这个国家的失策,它无法简单地解决。当然伊丽莎白和她的官员在爱尔兰的政策无疑加剧了这场冲突,但它还是有战略原因的。

伊丽莎白给她的继承人留下了一个困难的、不稳定的国家。尤其在经济和宗教上许多问题没有解决。她最主要的贡献在于她关心她的臣民,捍卫了她的统治,使用了好的顾问,她的统治帮助英格兰避免了经济上的危机和宗教战争。但17世纪中,这场战争还是在拥护查理一世的保皇派和克伦威尔领导的新教徒间爆发了。

编辑本段

大众文化

在电影电视中,伊丽莎白女王的形象时常出现。包括:

电影

Florence Eldridge出演,Mary of Scotland(1936)

Flora Robson出演,Fire Over England(1937),The Lion Has Wings(1939),TheSea Hawk(1940)

贝蒂·戴维斯出演,《伊丽莎白与埃塞克斯的私生活》(The Private Lives of Elizabeth andEssex,1939),《童贞女王》(The Virgin Queen,1955)

珍·西蒙斯(Jean Simmons)出演,Young Bess(1953)

Agnes Moorehead出演,The Story of Mankind(1957)

Quentin Crisp出演,Orlando(1993)

凯特·布兰琪出演,《伊丽莎白》(Elizabeth,1998,获奥斯卡最佳女主角提名),及其续集《伊丽莎白:辉煌年代》(Elizabeth: The GoldenAge,获奥斯卡最佳女主角提名)

茱蒂·丹契(Judi Dench)出演,《莎翁情史》(Shakespeare inLove,1998,获奥斯卡最佳女配角奖)

电视

Glenda Jackson出演,BBC电视剧集Elizabeth R(1971),获艾美奖

Miranda Richardson出演,BBC情景喜剧《黑爵士》Blackadder第二季

Anne-Marie Duff出演,BBC四集电视剧The Virgin Queen(2005)

海伦·米伦(Helen Mirren)出演,Channel 4二集电视剧Elizabeth I(2005/06),获艾美奖

[2]前任:

玛丽一世 英格兰女王

爱尔兰女王

自称法国国王

1558-1603 继任:

詹姆士一世

Elizabeth I (7 September 1533 – 24 March 1603) was queen regnantof England and Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death.Sometimes called "The Virgin Queen", "Gloriana" or "Good QueenBess", Elizabeth was the fifth and last monarch of the Tudordynasty. The daughter of Henry VIII, she was born a princess, buther mother, Anne Boleyn, was executed two and a half years afterher birth, and Elizabeth was declared illegitimate. On his death in1553, her half-brother, Edward VI, bequeathed the crown to LadyJane Grey, cutting his two half-sisters, Elizabeth and the CatholicMary, out of the succession in spite of statute law to thecontrary. His will was set aside, Mary became queen, and Lady JaneGrey was executed. In 1558, Elizabeth succeeded her half-sister,during whose reign she had been imprisoned for nearly a year onsuspicion of supporting Protestant rebels.

Elizabeth set out to rule by good counsel,[1] and she dependedheavily on a group of trusted advisers led by William Cecil, BaronBurghley. One of her first moves as queen was the establishment ofan English Protestant church, of which she became the SupremeGovernor. This Elizabethan Religious Settlement later evolved intotoday's Church of England. It was expected that Elizabeth wouldmarry and produce an heir so as to continue the Tudor line. Shenever did, however, despite numerous courtships. As she grew older,Elizabeth became famous for her virginity, and a cult grew uparound her which was celebrated in the portraits, pageants, andliterature of the day.

In government, Elizabeth was more moderate than her father andhalf-siblings had been.[2] One of her mottoes was "video et taceo"("I see, and say nothing").[3] In religion she was relativelytolerant, avoiding systematic persecution. After 1570, when thepope declared her illegitimate and released her subjects fromobedience to her, several conspiracies threatened her life. Allplots were defeated, however, with the help of her ministers'secret service. Elizabeth was cautious in foreign affairs, movingbetween the major powers of France and Spain. She onlyhalf-heartedly supported a number of ineffective, poorly resourcedmilitary campaigns in the Netherlands, France, and Ireland. In themid-1580s, war with Spain could no longer be avoided, and whenSpain finally decided to attempt to conquer England in 1588, thefailure of the Spanish Armada associated her with one of thegreatest military victories in English history.

Elizabeth's reign is known as the Elizabethan era, famous above allfor the flourishing of English drama, led by playwrights such asWilliam Shakespeare and Christopher Marlowe, and for the seafaringprowess of English adventurers such as Sir Francis Drake. Somehistorians are more reserved in their assessment. They depictElizabeth as a short-tempered, sometimes indecisive ruler,[4] whoenjoyed more than her share of luck. Towards the end of her reign,a series of economic and military problems weakened her popularity.Elizabeth is acknowledged as a charismatic performer and a doggedsurvivor, in an age when government was ramshackle and limited andwhen monarchs in neighbouring countries faced internal problemsthat jeopardised their thrones. Such was the case with Elizabeth'srival, Mary, Queen of Scots, whom she imprisoned in 1568 andeventually had executed in 1587. After the short reigns ofElizabeth's half-siblings, her 44 years on the throne providedwelcome stability for the kingdom and helped forge a sense ofnational identity.[2]Contents [hide]

1 Early life

2 Thomas Seymour

3 Mary I's reign

4 Accession

5 Church settlement

6 Marriage question

6.1 Robert Dudley

6.2 Political aspects

7 Mary, Queen of Scots

7.1 Mary and the Catholic cause

8 Wars and overseas trade

8.1 Netherlands expedition

8.2 Spanish Armada

8.3 Supporting Henry IV of France

8.4 Ireland

8.5 Russia

8.6 Barbary states, Ottoman Empire

9 Later years

10 Death

11 Legacy and memory

12 Ancestry

12.1 Family tree

12.2 Ahnentafel

13 See also

14 Notes

15 References

16 Further reading

16.1 Primary sources and early histories

16.2 Historiography and memory

17 External links

Early life

Elizabeth was the only child of Henry VIII and Anne Boleyn, who didnot bear a male heir and was executed less than three years afterElizabeth's birth.

Elizabeth was born at Greenwich Palace and was named after both hergrandmothers, Elizabeth of York and Elizabeth Howard.[5] She wasthe second child of Henry VIII of England born in wedlock tosurvive infancy. Her mother was Henry's second wife, Anne Boleyn.At birth, Elizabeth was the heiress presumptive to the throne ofEngland. Her older half-sister, Mary, had lost her position as alegitimate heir when Henry annulled his marriage to Mary's mother,Catherine of Aragon, in order to marry Anne and sire a male heir toensure the Tudor succession.[6][7] Elizabeth was baptised on 10September; Archbishop Thomas Cranmer, the Marquess of Exeter, theDuchess of Norfolk and the Dowager Marchioness of Dorset stood asher four godparents.

When Elizabeth was two years and eight months old, her mother wasexecuted on 19 May 1536.[8] Elizabeth was declared illegitimate anddeprived of the title of princess.[9] Eleven days after AnneBoleyn's death, Henry married Jane Seymour, but she died shortlyafter the birth of their son, Prince Edward, in 1537. From hisbirth, Edward was undisputed heir apparent to the throne. Elizabethwas placed in his household and carried the chrisom, or baptismalcloth, at his christening.[10]

The Lady Elizabeth in about 1546, by an unknown artist

Elizabeth's first Lady Mistress, Margaret Bryan, wrote that she was"as toward a child and as gentle of conditions as ever I knew anyin my life".[11] By the autumn of 1537, Elizabeth was in the careof Blanche Herbert, Lady Troy, who remained her Lady Mistress untilher retirement in late 1545 or early 1546.[12] CatherineChampernowne, better known by her later, married name of Catherine"Kat" Ashley, was appointed as Elizabeth's governess in 1537, andshe remained Elizabeth's friend until her death in 1565, whenBlanche Parry succeeded her as Chief Gentlewoman of the PrivyChamber.[13] Champernowne taught Elizabeth four languages: French,Flemish, Italian and Spanish.[14] By the time William Grindalbecame her tutor in 1544, Elizabeth could write English, Latin, andItalian. Under Grindal, a talented and skilful tutor, she alsoprogressed in French and Greek.[15] After Grindal died in 1548,Elizabeth received her education under Roger Ascham, a sympatheticteacher who believed that learning should be engaging.[16] By thetime her formal education ended in 1550, she was one of the besteducated women of her generation.[17] By the end of her life,Elizabeth was also reputed to speak Welsh, Cornish, Scottish andIrish in addition to English. The Venetian ambassador stated in1603 that she "possessed [these] languages so thoroughly that eachappeared to be her native tongue".[18] Historian Mark Stoylesuggests that she was probably taught Cornish by William Killigrew,Groom of the Privy Chamber and later Chamberlain of theExchequer.[19]

Thomas Seymour

The Miroir or Glasse of the Synneful Soul, a translation from theFrench, by Elizabeth, presented to Catherine Parr in 1544. Theembroidered binding with the monogram KP for "Katherine Parr" isbelieved to have been worked by Elizabeth.[20]

Henry VIII died in 1547; Elizabeth's half-brother, Edward VI,became king at age nine. Catherine Parr, Henry's widow, soonmarried Thomas Seymour of Sudeley, Edward VI's uncle and thebrother of the Lord Protector, Edward Seymour, Duke of Somerset.The couple took Elizabeth into their household at Chelsea. ThereElizabeth experienced an emotional crisis that some historiansbelieve affected her for the rest of her life.[21] Seymour,approaching age 40 but having charm and "a powerful sexappeal",[21] engaged in romps and horseplay with the 14-year-oldElizabeth. These included entering her bedroom in his nightgown,tickling her and slapping her on the buttocks. Parr, rather thanconfront her husband over his inappropriate activities, joined in.Twice she accompanied him in tickling Elizabeth, and once held herwhile he cut her black gown "into a thousand pieces."[22] However,after Parr discovered the pair in an embrace, she ended this stateof affairs.[23] In May 1548, Elizabeth was sent away.

However, Thomas Seymour continued scheming to control the royalfamily and tried to have himself appointed the governor of theKing's person.[24][25] When Parr died after childbirth on 5September 1548, he renewed his attentions towards Elizabeth, intenton marrying her.[26] The details of his former behaviour towardsElizabeth emerged,[27] and for his brother and the council, thiswas the last straw.[28] In January 1549, Seymour was arrested onsuspicion of plotting to marry Elizabeth and overthrow his brother.Elizabeth, living at Hatfield House, would admit nothing. Herstubbornness exasperated her interrogator, Sir Robert Tyrwhitt, whoreported, "I do see it in her face that she is guilty".[28] Seymourwas beheaded on 20 March 1549.

Mary I's reign

Mary I, by Anthonis Mor, 1554

Edward VI died on 6 July 1553, aged 15. His will swept aside theSuccession to the Crown Act 1543, excluded both Mary and Elizabethfrom the succession, and instead declared as his heir Lady JaneGrey, granddaughter of Henry VIII's sister Mary, Duchess ofSuffolk. Lady Jane was proclaimed queen by the Privy Council, buther support quickly crumbled, and she was deposed after nine days.Mary rode triumphantly into London, with Elizabeth at herside.[29]

The show of solidarity between the sisters did not last long. Mary,a devout Catholic, was determined to crush the Protestant faith inwhich Elizabeth had been educated, and she ordered that everyoneattend Catholic Mass; Elizabeth had to outwardly conform. Mary'sinitial popularity ebbed away in 1554 when she announced plans tomarry Prince Philip of Spain, the son of Emperor Charles V and anactive Catholic.[30] Discontent spread rapidly through the country,and many looked to Elizabeth as a focus for their opposition toMary's religious policies.

In January and February 1554, Wyatt's rebellion broke out; it wassoon suppressed.[31] Elizabeth was brought to court, andinterrogated regarding her role, and on 18 March, she wasimprisoned in the Tower of London. Elizabeth fervently protestedher innocence.[32] Though it is unlikely that she had plotted withthe rebels, some of them were known to have approached her. Mary'sclosest confidant, Charles V's ambassador Simon Renard, argued thather throne would never be safe while Elizabeth lived; and theChancellor, Stephen Gardiner, worked to have Elizabeth put ontrial.[33] Elizabeth's supporters in the government, including LordPaget, convinced Mary to spare her sister in the absence of hardevidence against her. Instead, on 22 May, Elizabeth was moved fromthe Tower to Woodstock, where she was to spend almost a year underhouse arrest in the charge of Sir Henry Bedingfield. Crowds cheeredher all along the way.[34][35]

The remaining wing of the Old Palace, Hatfield House. It was herethat Elizabeth was told of her sister's death in November1558.

On 17 April 1555, Elizabeth was recalled to court to attend thefinal stages of Mary's apparent pregnancy. If Mary and her childdied, Elizabeth would become queen. If, on the other hand, Marygave birth to a healthy child, Elizabeth's chances of becomingqueen would recede sharply. When it became clear that Mary was notpregnant, no one believed any longer that she could have achild.[36] Elizabeth's succession seemed assured.[37]

King Philip, who ascended the Spanish throne in 1556, acknowledgedthe new political reality and cultivated his sister-in-law. She wasa better ally than the chief alternative, Mary, Queen of Scots, whohad grown up in France and was betrothed to the Dauphin ofFrance.[38] When his wife fell ill in 1558, King Philip sent theCount of Feria to consult with Elizabeth.[39] This interview wasconducted at Hatfield House, where she had returned to live inOctober 1555. By October 1558, Elizabeth was already making plansfor her government. On 6 November, Mary recognised Elizabeth as herheir.[40] On 17 November 1558, Mary died and Elizabeth succeeded tothe throne.

Accession

Elizabeth became queen at the age of 25, and declared herintentions to her Council and other peers who had come to Hatfieldto swear allegiance. The speech contains the first record of heradoption of the mediaeval political theology of the sovereign's"two bodies": the body natural and the body politic:[41]

Elizabeth I in her coronation robes, patterned with Tudor roses andtrimmed with ermine.

My lords, the law of nature moves me to sorrow for my sister; theburden that is fallen upon me makes me amazed, and yet, consideringI am God's creature, ordained to obey His appointment, I willthereto yield, desiring from the bottom of my heart that I may haveassistance of His grace to be the minister of His heavenly will inthis office now committed to me. And as I am but one body naturallyconsidered, though by His permission a body politic to govern, soshall I desire you all ... to be assistant to me, that I with myruling and you with your service may make a good account toAlmighty God and leave some comfort to our posterity on earth. Imean to direct all my actions by good advice and counsel.[42]

As her triumphal progress wound through the city on the eve of thecoronation ceremony, she was welcomed wholeheartedly by thecitizens and greeted by orations and pageants, most with a strongProtestant flavour. Elizabeth's open and gracious responsesendeared her to the spectators, who were "wonderfullyravished".[43] The following day, 15 January 1559, Elizabeth wascrowned and anointed by Owen Oglethorpe, the Catholic bishop ofCarlisle, in Westminster Abbey. She was then presented for thepeople's acceptance, amidst a deafening noise of organs, fifes,trumpets, drums, and bells.[44]

Church settlement

Main article: Elizabethan Religious Settlement

Elizabeth's personal religious convictions have been much debatedby scholars. She was a Protestant, but kept Catholic symbols (suchas the crucifix), and downplayed the role of sermons in defiance ofa key Protestant belief.[45]

In terms of public policy she favoured pragmatism in dealing withreligious matters. The question of her legitimacy was a keyconcern: although she was technically illegitimate under bothProtestant and Catholic law, her retroactively declaredillegitimacy under the English church was not a serious barcompared to having never been legitimate as the Catholics claimedshe was. For this reason alone, it was never in serious doubt thatElizabeth would embrace Protestantism.

Elizabeth and her advisors perceived the threat of a Catholiccrusade against heretical England. Elizabeth therefore sought aProtestant solution that would not offend Catholics too greatlywhile addressing the desires of English Protestants; she would nottolerate the more radical Puritans though, who were pushing forfar-reaching reforms.[46] As a result, the parliament of 1559started to legislate for a church based on the Protestantsettlement of Edward VI, with the monarch as its head, but withmany Catholic elements, such as priestly vestments.[47]

The House of Commons backed the proposals strongly, but the bill ofsupremacy met opposition in the House of Lords, particularly fromthe bishops. Elizabeth was fortunate that many bishoprics werevacant at the time, including the Archbishopric ofCanterbury.[48][49] This enabled supporters amongst peers tooutvote the bishops and conservative peers. Nevertheless, Elizabethwas forced to accept the title of Supreme Governor of the Church ofEngland rather than the more contentious title of Supreme Head,which many thought unacceptable for a woman to bear. The new Act ofSupremacy became law on 8 May 1559. All public officials were toswear an oath of loyalty to the monarch as the supreme governor orrisk disqualification from office; the heresy laws were repealed,to avoid a repeat of the persecution of dissenters practised byMary. At the same time, a new Act of Uniformity was passed, whichmade attendance at church and the use of an adapted version of the1552 Book of Common Prayer compulsory, though the penalties forrecusancy, or failure to attend and conform, were notextreme.[50]

Marriage question

Elizabeth and her favourite, Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester, c.1575. Pair of stamp-sized miniatures by Nicholas Hilliard.[51] TheQueen's friendship with Dudley lasted for over thirty years, untilhis death.

From the start of Elizabeth's reign, it was expected that she wouldmarry and the question arose to whom. She never did, although shereceived many offers for her hand; the reasons for this are notclear. Historians have speculated that Thomas Seymour had put heroff sexual relationships, or that she knew herself to beinfertile.[52][53] She considered several suitors until she wasabout fifty. Her last courtship was with Francis, Duke of Anjou, 22years her junior. While risking possible loss of power like hersister, who played into the hands of King Philip II of Spain,marriage offered the chance of an heir.[54] However, the choice ofa husband might also provoke political instability or eveninsurrection.[55]

Robert Dudley

In the spring of 1559 it became evident that Elizabeth was in lovewith her childhood friend Robert Dudley.[56] It was said that AmyRobsart, his wife, was suffering from a "malady in one of herbreasts", and that the Queen would like to marry Dudley if his wifeshould die.[57] By the autumn of 1559 several foreign suitors werevying for Elizabeth's hand; their impatient envoys engaged in evermore scandalous talk and reported that a marriage with herfavourite was not welcome in England:[58] "There is not a man whodoes not cry out on him and her with indignation ... she will marrynone but the favoured Robert".[59] Amy Dudley died in September1560 from a fall from a flight of stairs and, despite the coroner'sinquest finding of accident, many people suspected Dudley to havearranged her death so that he could marry the queen.[60] Elizabethseriously considered marrying Dudley for some time. However,William Cecil, Nicholas Throckmorton, and some conservative peersmade their disapproval unmistakably clear.[61] There were evenrumours that the nobility would rise if the marriage tookplace.[62]

Among other marriages being considered for the queen, Robert Dudleywas regarded as a possible candidate for nearly another decade.[63]Elizabeth was extremely jealous of his affections, even when she nolonger meant to marry him herself.[64] In 1564 Elizabeth raisedDudley to the peerage as Earl of Leicester. He finally remarried in1578, to which the queen reacted with repeated scenes ofdispleasure and lifelong hatred towards his wife.[65] Still, Dudleyalways "remained at the centre of [Elizabeth's] emotional life", ashistorian Susan Doran has described the situation.[66] He diedshortly after the defeat of the Armada. After Elizabeth's owndeath, a note from him was found among her most personalbelongings, marked "his last letter" in her handwriting.[67]

Political aspects

Francis, Duke of Anjou, by Nicholas Hilliard. Elizabeth called theduke her "frog", finding him "not so deformed" as she had been ledto expect.[68]

Marriage negotiations constituted a key element in Elizabeth'sforeign policy.[69] She turned down Philip II's own hand in 1559,and negotiated for several years to marry his cousin ArchdukeCharles of Austria. By 1569, relations with the Habsburgs haddeteriorated, and Elizabeth considered marriage to two FrenchValois princes in turn, first Henry, Duke of Anjou, and later, from1572 to 1581, his brother Francis, Duke of Anjou, formerly Duke ofAlençon.[70] This last proposal was tied to a planned allianceagainst Spanish control of the Southern Netherlands.[71] Elizabethseems to have taken the courtship seriously for a time, and wore afrog-shaped earring that Anjou had sent her.[72]

In 1563, Elizabeth told an imperial envoy: "If I follow theinclination of my nature, it is this: beggar-woman and single, farrather than queen and married".[69] Later in the year, followingElizabeth's illness with smallpox, the succession question became aheated issue in Parliament. They urged the queen to marry ornominate an heir, to prevent a civil war upon her death. Sherefused to do either. In April she prorogued the Parliament, whichdid not reconvene until she needed its support to raise taxes in1566. Having promised to marry previously, she told an unrulyHouse:

I will never break the word of a prince spoken in public place, formy honour's sake. And therefore I say again, I will marry as soonas I can conveniently, if God take not him away with whom I mind tomarry, or myself, or else some other great let happen.[73]

By 1570, senior figures in the government privately accepted thatElizabeth would never marry or name a successor. William Cecil wasalready seeking solutions to the succession problem.[69] For herfailure to marry, Elizabeth was often accused ofirresponsibility.[74] Her silence, however, strengthened her ownpolitical security: she knew that if she named an heir, her thronewould be vulnerable to a coup; she remembered that the way "asecond person, as I have been" had been used as the focus of plotsagainst her predecessor.[75]

The "Hampden" portrait, by Steven van der Meulen, ca. 1563. This isthe earliest full-length portrait of the queen, made before theemergence of symbolic portraits representing the iconography of the"Virgin Queen".[76]

Elizabeth's unmarried status inspired a cult of virginity. Inpoetry and portraiture, she was depicted as a virgin or a goddessor both, not as a normal woman.[77] At first, only Elizabeth made avirtue of her virginity: in 1559, she told the Commons, "And, inthe end, this shall be for me sufficient, that a marble stone shalldeclare that a queen, having reigned such a time, lived and died avirgin".[78] Later on, poets and writers took up the theme andturned it into an iconography that exalted Elizabeth. Publictributes to the Virgin by 1578 acted as a coded assertion ofopposition to the queen's marriage negotiations with the Duke ofAlençon.[79]

Putting a positive spin on her marital status, Elizabeth insistedshe was married to her kingdom and subjects, under divineprotection. In 1599, she spoke of "all my husbands, my goodpeople".[80]

Mary, Queen of Scots

Elizabeth's first policy toward Scotland was to oppose the Frenchpresence there.[81] She feared that the French planned to invadeEngland and put Mary, Queen of Scots, who was considered by many tobe the heir to the English crown,[82] on the throne.[83] Elizabethwas persuaded to send a force into Scotland to aid the Protestantrebels, and though the campaign was inept, the resulting Treaty ofEdinburgh of July 1560 removed the French threat in the north.[84]When Mary returned to Scotland in 1561 to take up the reins ofpower, the country had an established Protestant church and was runby a council of Protestant nobles supported by Elizabeth.[85] Maryrefused to ratify the treaty.[86]

In 1563 Elizabeth proposed her own suitor, Robert Dudley, as ahusband for Mary, without asking either of the two peopleconcerned. Both proved unenthusiastic,[87] and in 1565 Mary marriedHenry Stuart, Lord Darnley, who carried his own claim to theEnglish throne. The marriage was the first of a series of errors ofjudgement by Mary that handed the victory to the ScottishProtestants and to Elizabeth. Darnley quickly became unpopular inScotland and then infamous for presiding over the murder of Mary'sItalian secretary David Rizzio. In February 1567, Darnley wasmurdered by conspirators almost certainly led by James Hepburn,Earl of Bothwell. Shortly afterwards, on 15 May 1567, Mary marriedBothwell, arousing suspicions that she had been party to the murderof her husband. Elizabeth wrote to her:

How could a worse choice be made for your honour than in such hasteto marry such a subject, who besides other and notorious lacks,public fame has charged with the murder of your late husband,besides the touching of yourself also in some part, though we trustin that behalf falsely.[88]

These events led rapidly to Mary's defeat and imprisonment in LochLeven Castle. The Scottish lords forced her to abdicate in favourof her son James, who had been born in June 1566. James was takento Stirling Castle to be raised as a Protestant. Mary escaped fromLoch Leven in 1568 but after another defeat fled across the borderinto England, where she had once been assured of support fromElizabeth. Elizabeth's first instinct was to restore her fellowmonarch; but she and her council instead chose to play safe. Ratherthan risk returning Mary to Scotland with an English army orsending her to France and the Catholic enemies of England, theydetained her in England, where she was imprisoned for the nextnineteen years.[89]

Mary and the Catholic cause

Sir Francis Walsingham, Principal Secretary 1573–1590. BeingElizabeth's spymaster, he uncovered several plots against herlife.

Mary was soon the focus for rebellion. In 1569 there was a majorCatholic rising in the North; the goal was to free Mary, marry herto Thomas Howard, 4th Duke of Norfolk, and put her on the Englishthrone.[90] After the rebels' defeat, over 750 of them wereexecuted on Elizabeth's orders.[91] In the belief that the revolthad been successful, Pope Pius V issued a bull in 1570, titledRegnans in Excelsis, which declared "Elizabeth, the pretended Queenof England and the servant of crime" to be excommunicate and aheretic, releasing all her subjects from any allegiance toher.[92][93] Catholics who obeyed her orders were threatened withexcommunication.[92] The papal bull provoked legislativeinitiatives against Catholics by Parliament, which were howevermitigated by Elizabeth's intervention.[94] In 1581, to convertEnglish subjects to Catholicism with "the intent" to withdraw themfrom their allegiance to Elizabeth was made a treasonable offence,carrying the death penalty.[95] From the 1570s missionary priestsfrom continental seminaries came to England secretly in the causeof the "reconversion of England".[93] Many suffered execution,engendering a cult of martyrdom.[93]

Regnans in Excelsis gave English Catholics a strong incentive tolook to Mary Stuart as the true sovereign of England. Mary may nothave been told of every Catholic plot to put her on the Englishthrone, but from the Ridolfi Plot of 1571 (which caused Mary'ssuitor, the Duke of Norfolk, to lose his head) to the BabingtonPlot of 1586, Elizabeth's spymaster Sir Francis Walsingham and theroyal council keenly assembled a case against her.[96] At first,Elizabeth resisted calls for Mary's death. By late 1586 she hadbeen persuaded to sanction her trial and execution on the evidenceof letters written during the Babington Plot.[97] Elizabeth'sproclamation of the sentence announced that "the said Mary,pretending title to the same Crown, had compassed and imaginedwithin the same realm divers things tending to the hurt, death anddestruction of our royal person."[98] On 8 February 1587, Mary wasbeheaded at Fotheringhay Castle, Northamptonshire.[99] After Mary'sexecution, Elizabeth claimed not to have ordered it and indeed mostaccounts have her telling Secretary Davidson, who brought her thewarrant to sign, not to dispatch the warrant even though she hadsigned it. The sincerity of Elizabeth's remorse and her motives fortelling Davidson not to execute the warrant have been called intoquestion both by her contemporaries and later historians.

Wars and overseas trade

Half groat of Elizabeth I

Elizabeth's foreign policy was largely defensive. The exception wasthe English occupation of Le Havre from October 1562 to June 1563,which ended in failure when Elizabeth's Huguenot allies joined withthe Catholics to retake the port. Elizabeth's intention had been toexchange Le Havre for Calais, lost to France in January 1558.[100]Only through the activities of her fleets did Elizabeth pursue anaggressive policy. This paid off in the war against Spain, 80% ofwhich was fought at sea.[101] She knighted Francis Drake after hiscircumnavigation of the globe from 1577 to 1580, and he won famefor his raids on Spanish ports and fleets. An element of piracy andself-enrichment drove Elizabethan seafarers, over which the queenhad little control.[102][103]

Netherlands expedition

After the occupation and loss of Le Havre in 1562–1563, Elizabethavoided military expeditions on the continent until 1585, when shesent an English army to aid the Protestant Dutch rebels againstPhilip II.[104] This followed the deaths in 1584 of the alliesWilliam the Silent, Prince of Orange, and Francis, Duke of Anjou,and the surrender of a series of Dutch towns to Alexander Farnese,Duke of Parma, Philip's governor of the Spanish Netherlands. InDecember 1584, an alliance between Philip II and the FrenchCatholic League at Joinville undermined the ability of Anjou'sbrother, Henry III of France, to counter Spanish domination of theNetherlands. It also extended Spanish influence along the channelcoast of France, where the Catholic League was strong, and exposedEngland to invasion.[104] The siege of Antwerp in the summer of1585 by the Duke of Parma necessitated some reaction on the part ofthe English and the Dutch. The outcome was the Treaty of Nonsuch ofAugust 1585, in which Elizabeth promised military support to theDutch.[105] The treaty marked the beginning of the Anglo-SpanishWar, which lasted until the Treaty of London in 1604.

The expedition was led by her former suitor, Robert Dudley, Earl ofLeicester. Elizabeth from the start did not really back this courseof action. Her strategy, to support the Dutch on the surface withan English army, while beginning secret peace talks with Spainwithin days of Leicester's arrival in Holland,[106] had necessarilyto be at odds with Leicester's, who wanted and was expected by theDutch to fight an active campaign. Elizabeth on the other hand,wanted him "to avoid at all costs any decisive action with theenemy".[107] He enraged Elizabeth by accepting the post ofGovernor-General from the Dutch States-General. Elizabeth saw thisas a Dutch ploy to force her to accept sovereignty over theNetherlands,[108] which so far she had always declined. She wroteto Leicester:

We could never have imagined (had we not seen it fall out inexperience) that a man raised up by ourself and extraordinarilyfavoured by us, above any other subject of this land, would have inso contemptible a sort broken our commandment in a cause that sogreatly touches us in honour....And therefore our express pleasureand commandment is that, all delays and excuses laid apart, you dopresently upon the duty of your allegiance obey and fulfillwhatsoever the bearer hereof shall direct you to do in our name.Whereof fail you not, as you will answer the contrary at yourutmost peril.[109]

Elizabeth's "commandment" was that her emissary read out herletters of disapproval publicly before the Dutch Council of State,Leicester having to stand nearby.[110] This public humiliation ofher "Lieutenant-General" combined with her continued talks for aseparate peace with Spain,[111] irreversibly undermined hisstanding among the Dutch. The military campaign was severelyhampered by Elizabeth's repeated refusals to send promised fundsfor her starving soldiers. Her unwillingness to commit herself tothe cause, Leicester's own shortcomings as a political and militaryleader and the faction-ridden and chaotic situation of Dutchpolitics were reasons for the campaign's failure.[112] Leicesterfinally resigned his command in December 1587.

Spanish Armada

Meanwhile, Sir Francis Drake had undertaken a major voyage againstSpanish ports and ships to the Caribbean in 1585 and 1586, and in1587 had made a successful raid on Cadiz, destroying the Spanishfleet of war ships intended for the Enterprise of England:[113]Philip II had decided to take the war to England.[114]

Portrait of Elizabeth to commemorate the defeat of the SpanishArmada (1588), depicted in the background. Elizabeth's hand restson the globe, symbolising her international power.

On 12 July 1588, the Spanish Armada, a great fleet of ships, setsail for the channel, planning to ferry a Spanish invasion forceunder the Duke of Parma to the coast of southeast England from theNetherlands. A combination of miscalculation,[115] misfortune, andan attack of English fire ships on 29 July off Gravelines whichdispersed the Spanish ships to the northeast defeated theArmada.[116] The Armada straggled home to Spain in shatteredremnants, after disastrous losses on the coast of Ireland (aftersome ships had tried to struggle back to Spain via the North Sea,and then back south past the west coast of Ireland).[117] Unawareof the Armada's fate, English militias mustered to defend thecountry under the Earl of Leicester's command. He invited Elizabethto inspect her troops at Tilbury in Essex on 8 August. Wearing asilver breastplate over a white velvet dress, she addressed them inone of her most famous speeches:

My loving people, we have been persuaded by some that are carefulof our safety, to take heed how we commit ourself to armedmultitudes for fear of treachery; but I assure you, I do not desireto live to distrust my faithful and loving people ... I know I havethe body but of a weak and feeble woman, but I have the heart andstomach of a king, and of a King of England too, and think foulscorn that Parma or Spain, or any Prince of Europe should dare toinvade the borders of my realm.[118]

When no invasion came, the nation rejoiced. Elizabeth's processionto a thanksgiving service at St Paul's Cathedral rivalled that ofher coronation as a spectacle.[117] The defeat of the armada was apotent propaganda victory, both for Elizabeth and for ProtestantEngland. The English took their delivery as a symbol of God'sfavour and of the nation's inviolability under a virgin queen.[101]However, the victory was not a turning point in the war, whichcontinued and often favoured Spain.[119] The Spanish stillcontrolled the Netherlands, and the threat of invasionremained.[114] Sir Walter Raleigh claimed after her death thatElizabeth's caution had impeded the war against Spain:

If the late queen would have believed her men of war as she did herscribes, we had in her time beaten that great empire in pieces andmade their kings of figs and oranges as in old times. But herMajesty did all by halves, and by petty invasions taught theSpaniard how to defend himself, and to see his ownweakness.[120]

Though some historians have criticised Elizabeth on similargrounds,[121] Raleigh's verdict has more often been judged unfair.Elizabeth had good reason not to place too much trust in hercommanders, who once in action tended, as she put it herself, "tobe transported with an haviour of vainglory".[122]

Supporting Henry IV of France

Coat of arms of Queen Elizabeth I, with her personal motto: "Sempereadem" or "always the same"

When the Protestant Henry IV inherited the French throne in 1589,Elizabeth sent him military support. It was her first venture intoFrance since the retreat from Le Havre in 1563. Henry's successionwas strongly contested by the Catholic League and by Philip II, andElizabeth feared a Spanish takeover of the channel ports. Thesubsequent English campaigns in France, however, were disorganisedand ineffective.[123] Lord Willoughby, largely ignoring Elizabeth'sorders, roamed northern France to little effect, with an army of4,000 men. He withdrew in disarray in December 1589, having losthalf his troops. In 1591, the campaign of John Norreys, who led3,000 men to Brittany, was even more of a disaster. As for all suchexpeditions, Elizabeth was unwilling to invest in the supplies andreinforcements requested by the commanders. Norreys left for Londonto plead in person for more support. In his absence, a CatholicLeague army almost destroyed the remains of his army at Craon,north-west France, in May 1591. In July, Elizabeth sent out anotherforce under Robert Devereux, Earl of Essex, to help Henry IV inbesieging Rouen. The result was just as dismal. Essex accomplishednothing and returned home in January 1592. Henry abandoned thesiege in April.[124] As usual, Elizabeth lacked control over hercommanders once they were abroad. "Where he is, or what he doth, orwhat he is to do," she wrote of Essex, "we areignorant".[125]

Ireland

Main article: Tudor conquest of Ireland

Although Ireland was one of her two kingdoms, Elizabeth faced ahostile, and in places virtually autonomous,[126] Irish populationthat adhered to Catholicism and was willing to defy her authorityand plot with her enemies. Her policy there was to grant land toher courtiers and prevent the rebels from giving Spain a base fromwhich to attack England.[127] In the course of a series ofuprisings, Crown forces pursued scorched-earth tactics, burning theland and slaughtering man, woman and child. During a revolt inMunster led by Gerald FitzGerald, Earl of Desmond, in 1582, anestimated 30,000 Irish people starved to death. The poet andcolonist Edmund Spenser wrote that the victims "were brought tosuch wretchedness as that any stony heart would have rued thesame".[128] Elizabeth advised her commanders that the Irish, "thatrude and barbarous nation", be well treated; but she showed noremorse when force and bloodshed were deemed necessary.[129]

Between 1594 and 1603, Elizabeth faced her most severe test inIreland during the Nine Years' War, a revolt that took place at theheight of hostilities with Spain, who backed the rebel leader, HughO'Neill, Earl of Tyrone.[130] In spring 1599, Elizabeth sent RobertDevereux, 2nd Earl of Essex, to put the revolt down. To herfrustration,[131] he made little progress and returned to Englandin defiance of her orders. He was replaced by Charles Blount, LordMountjoy, who took three years to defeat the rebels. O'Neillfinally surrendered in 1603, a few days after Elizabeth'sdeath.[132] Soon afterwards, a peace treaty was signed betweenEngland and Spain.

Russia

Ivan the Terrible shows his treasures to Elizabeth's ambassador.Painting by Alexander Litovchenko, 1875

Elizabeth continued to maintain the diplomatic relations with theTsardom of Russia originally established by her deceased brother.She often wrote to its then ruler, Tsar Ivan IV ("Ivan theTerrible"), on amicable terms, though the Tsar was often annoyed byher focus on commerce rather than on the possibility of a militaryalliance. The Tsar even proposed to her once, and during his laterreign, asked for a guarantee to be granted asylum in England shouldhis rule be jeopardised. Upon Ivan's death, he was succeeded by hissimple-minded son Feodor. Unlike his father, Feodor had noenthusiasm in maintaining exclusive trading rights with England.Feodor declared his kingdom open to all foreigners, and dismissedthe English ambassador Sir Jerome Bowes, whose pomposity had beentolerated by the new Tsar's late father. Elizabeth sent a newambassador, Dr. Giles Fletcher, to demand from the regent BorisGodunov that he convince the Tsar to reconsider. The negotiationsfailed, due to Fletcher addressing Feodor with two of his titlesomitted. Elizabeth continued to appeal to Feodor in half appealing,half reproachful letters. She proposed an alliance, something whichshe had refused to do when offered one by Feodor's father, but wasturned down.[133]

Barbary states, Ottoman Empire

Abd el-Ouahed ben Messaoud, Moorish ambassador of the BarbaryStates to the Court of Queen Elizabeth I in 1600.[134]

Trade and diplomatic relations developed between England and theBarbary states during the rule of Elizabeth.[135][136] Englandestablished a trading relationship with Morocco in opposition toSpain, selling armour, ammunition, timber, and metal in exchangefor Moroccan sugar, in spite of a Papal ban.[137] In 1600, Abdel-Ouahed ben Messaoud, the principal secretary to the Moroccanruler Mulai Ahmad al-Mansur, visited England as an ambassador tothe court of queen Elizabeth I,[135][138] in order to negotiate anAnglo-Moroccan alliance against Spain.[134][135] Elizabeth "agreedto sell munitions supplies to Morocco, and she and Mulai Ahmadal-Mansur talked on and off about mounting a joint operationagainst the Spanish".[139] Discussions however remainedinconclusive, and both rulers died within two years of theembassy.[140]

Diplomatic relations were also established with the Ottoman Empirewith the chartering of the Levant Company and the dispatch of thefirst English ambassador to the Porte, William Harborne, in1578.[139] For the first time, a Treaty of Commerce was signed in1580.[141] Numerous envoys were dispatched in both directions andepistolar exchanges occurred between Elizabeth and Sultan MuradIII.[139] In one correspondence, Murad entertained the notion thatIslam and Protestantism had "much more in common than either didwith Roman Catholicism, as both rejected the worship of idols", andargued for an alliance between England and the Ottoman Empire.[142]To the dismay of Catholic Europe, England exported tin and lead(for cannon-casting) and ammunitions to the Ottoman Empire, andElizabeth seriously discussed joint military operations with MuradIII during the outbreak of war with Spain in 1585, as FrancisWalsingham was lobbying for a direct Ottoman military involvementagainst the common Spanish enemy.[143]

Later years

Portrait of Elizabeth I attributed to Marcus Gheeraerts the Youngeror his studio, ca. 1595.

The period after the defeat of the Spanish Armada in 1588 broughtnew difficulties for Elizabeth that lasted the fifteen years untilthe end of her reign.[119] The conflicts with Spain and in Irelanddragged on, the tax burden grew heavier, and the economy was hit bypoor harvests and the cost of war. Prices rose and the standard ofliving fell.[144][145] During this time, repression of Catholicsintensified, and Elizabeth authorised commissions in 1591 tointerrogate and monitor Catholic householders.[146] To maintain theillusion of peace and prosperity, she increasingly relied oninternal spies and propaganda.[144] In her last years, mountingcriticism reflected a decline in the public's affection forher.[147]

One of the causes for this "second reign" of Elizabeth, as it issometimes called,[148] was the different character of Elizabeth'sgoverning body, the privy council in the 1590s. A new generationwas in power. With the exception of Lord Burghley, the mostimportant politicians had died around 1590: The Earl of Leicesterin 1588, Sir Francis Walsingham in 1590, Sir Christopher Hatton in1591.[149] Factional strife in the government, which had notexisted in a noteworthy form before the 1590s,[150] now became itshallmark.[151] A bitter rivalry between the Earl of Essex andRobert Cecil, son of Lord Burghley, and their respective adherents,for the most powerful positions in the state marred politics.[152]The queen's personal authority was lessening,[153] as is shown inthe affair of Dr. Lopez, her trusted physician. When he was wronglyaccused by the Earl of Essex of treason out of personal pique, shecould not prevent his execution, although she had been angry abouthis arrest and seems not to have believed in his guilt(1594).[154]

Elizabeth, during the last years of her reign, came to rely ongranting monopolies as a cost-free system of patronage rather thanask Parliament for more subsidies in a time of war.[155] Thepractice soon led to price-fixing, the enrichment of courtiers atthe public's expense, and widespread resentment.[156] Thisculminated in agitation in the House of Commons during theparliament of 1601.[157] In her famous "Golden Speech" of 30November 1601, Elizabeth professed ignorance of the abuses and wonthe members over with promises and her usual appeal to theemotions:[158]

Who keeps their sovereign from the lapse of error, in which, byignorance and not by intent they might have fallen, what thank theydeserve, we know, though you may guess. And as nothing is more dearto us than the loving conservation of our subjects' hearts, what anundeserved doubt might we have incurred if the abusers of ourliberality, the thrallers of our people, the wringers of the poor,had not been told us![159]

Robert Devereux, 2nd Earl of Essex, by William Segar, 1588

This same period of economic and political uncertainty, however,produced an unsurpassed literary flowering in England.[160] Thefirst signs of a new literary movement had appeared at the end ofthe second decade of Elizabeth's reign, with John Lyly's Euphuesand Edmund Spenser's The Shepheardes Calender in 1578. During the1590s, some of the great names of English literature entered theirmaturity, including William Shakespeare and Christopher Marlowe.During this period and into the Jacobean era that followed, theEnglish theatre reached its highest peaks.[161] The notion of agreat Elizabethan age depends largely on the builders, dramatists,poets, and musicians who were active during Elizabeth's reign. Theyowed little directly to the queen, who was never a major patron ofthe arts.[162]

As Elizabeth aged her image gradually changed. She was portrayed asBelphoebe or Astraea, and after the Armada, as Gloriana, theeternally youthful Faerie Queene of Edmund Spenser's poem. Herpainted portraits became less realistic and more a set of enigmaticicons that made her look much younger than she was. In fact, herskin had been scarred by smallpox in 1562, leaving her half baldand dependent on wigs and cosmetics.[163] Sir Walter Raleigh calledher "a lady whom time had surprised".[164] However, the moreElizabeth's beauty faded, the more her courtiers praisedit.[163]

Elizabeth was happy to play the part,[165] but it is possible thatin the last decade of her life she began to believe her ownperformance. She became fond and indulgent of the charming butpetulant young Robert Devereux, Earl of Essex, who was Leicester'sstepson and took liberties with her for which she forgave him.[166]She repeatedly appointed him to military posts despite his growingrecord of irresponsibility. After Essex's desertion of his commandin Ireland in 1599, Elizabeth had him placed under house arrest andthe following year deprived him of his monopolies.[167] In February1601, the earl tried to raise a rebellion in London. He intended toseize the queen but few rallied to his support, and he was beheadedon 25 February. Elizabeth knew that her own misjudgements werepartly to blame for this turn of events. An observer reported in1602 that "Her delight is to sit in the dark, and sometimes withshedding tears to bewail Essex".[168]

Death

Elizabeth I. The "Rainbow Portrait", c. 1600, an allegoricalrepresentation of the Queen, become ageless in her old age

Elizabeth's senior advisor, Burghley, died on 4 August 1598. Hispolitical mantle passed to his son, Robert Cecil, who soon becamethe leader of the government.[169] One task he addressed was toprepare the way for a smooth succession. Since Elizabeth wouldnever name her successor, Cecil was obliged to proceed insecret.[170] He therefore entered into a coded negotiation withJames VI of Scotland, who had a strong but unrecognised claim.[171]Cecil coached the impatient James to humour Elizabeth and "securethe heart of the highest, to whose sex and quality nothing is soimproper as either needless expostulations or over much curiosityin her own actions".[172] The advice worked. James's tone delightedElizabeth, who responded: "So trust I that you will not doubt butthat your last letters are so acceptably taken as my thanks cannotbe lacking for the same, but yield them to you in gratefulsort".[173] In historian J. E. Neale's view, Elizabeth may not havedeclared her wishes openly to James, but she made them known with"unmistakable if veiled phrases".[174]

The Queen's health remained fair until the autumn of 1602, when aseries of deaths among her friends plunged her into a severedepression. In February 1603, the death of Catherine Howard,Countess of Nottingham, the niece of her cousin and close friendCatherine, Lady Knollys, came as a particular blow. In March,Elizabeth fell sick and remained in a "settled and unremovablemelancholy".[175] She died on 24 March 1603 at Richmond Palace,between two and three in the morning. A few hours later, Cecil andthe council set their plans in motion and proclaimed James VI ofScotland as king of England.[176]

Elizabeth's coffin was carried downriver at night to Whitehall, ona barge lit with torches. At her funeral on 28 April, the coffinwas taken to Westminster Abbey on a hearse drawn by four horseshung with black velvet. In the words of the chronicler JohnStow:

Westminster was surcharged with multitudes of all sorts of peoplein their streets, houses, windows, leads and gutters, that came outto see the obsequy, and when they beheld her statue lying upon thecoffin, there was such a general sighing, groaning and weeping asthe like hath not been seen or known in the memory ofman.[177]

Elizabeth's funeral cortège, 1603, with banners of her royalancestors

Elizabeth was interred in Westminster Abbey in a tomb she shareswith her half-sister, Mary. The Latin inscription on their tomb,"Regno consortes & urna, hic obdormimus Elizabetha et Mariasorores, in spe resurrectionis", translates to "Consorts in realmand tomb, here we sleep, Elizabeth and Mary, sisters, in hope ofresurrection".[178]

Legacy and memory

Further information: Cultural depictions of Elizabeth I ofEngland

Elizabeth was lamented by many of her subjects, but others wererelieved at her death.[179] Expectations of King James started highbut then declined, so by the 1620s there was a nostalgic revival ofthe cult of Elizabeth.[180] Elizabeth was praised as a heroine ofthe Protestant cause and the ruler of a golden age. James wasdepicted as a Catholic sympathiser, presiding over a corruptcourt.[181] The triumphalist image that Elizabeth had cultivatedtowards the end of her reign, against a background of factionalismand military and economic difficulties,[182] was taken at facevalue and her reputation inflated. Godfrey Goodman, Bishop ofGloucester, recalled: "When we had experience of a Scottishgovernment, the Queen did seem to revive. Then was her memory muchmagnified."[183] Elizabeth's reign became idealised as a time whencrown, church and parliament had worked in constitutionalbalance.[184]

Elizabeth I, painted after 1620, during the first revival ofinterest in her reign. Time sleeps on her right and Death looksover her left shoulder; two putti hold the crown above herhead.[185]

The picture of Elizabeth painted by her Protestant admirers of theearly 17th century has proved lasting and influential.[186] Hermemory was also revived during the Napoleonic Wars, when the nationagain found itself on the brink of invasion.[187] In the Victorianera, the Elizabethan legend was adapted to the imperial ideology ofthe day,[179][188] and in the mid-20th century, Elizabeth was aromantic symbol of the national resistance to foreignthreat.[189][190] Historians of that period, such as J. E. Neale(1934) and A. L. Rowse (1950), interpreted Elizabeth's reign as agolden age of progress.[191] Neale and Rowse also idealised theQueen personally: she always did everything right; her moreunpleasant traits were ignored or explained as signs ofstress.[192]

Recent historians, however, have taken a more complicated view ofElizabeth.[193] Her reign is famous for the defeat of the Armada,and for successful raids against the Spanish, such as those onCádiz in 1587 and 1596, but some historians point to militaryfailures on land and at sea.[123] In Ireland, Elizabeth's forcesultimately prevailed, but their tactics stain her record.[194]Rather than as a brave defender of the Protestant nations againstSpain and the Habsburgs, she is more often regarded as cautious inher foreign policies. She offered very limited aid to foreignProtestants and failed to provide her commanders with the funds tomake a difference abroad.[195]

Elizabeth established an English church that helped shape anational identity and remains in place today.[196][197][198] Thosewho praised her later as a Protestant heroine overlooked herrefusal to drop all practices of Catholic origin from the Church ofEngland.[199] Historians note that in her day, strict Protestantsregarded the Acts of Settlement and Uniformity of 1559 as acompromise.[200][201] In fact, Elizabeth believed that faith waspersonal and did not wish, as Francis Bacon put it, to "makewindows into men's hearts and secret thoughts".[202][203]

Though Elizabeth followed a largely defensive foreign policy, herreign raised England's status abroad. "She is only a woman, onlymistress of half an island," marvelled Pope Sixtus V, "and yet shemakes herself feared by Spain, by France, by the Empire, byall".[204] Under Elizabeth, the nation gained a new self-confidenceand sense of sovereignty, as Christendom fragmented.[180][205][206]Elizabeth was the first Tudor to recognise that a monarch ruled bypopular consent.[207] She therefore always worked with parliamentand advisers she could trust to tell her the truth—a style ofgovernment that her Stuart successors failed to follow. Somehistorians have called her lucky;[204] she believed that God wasprotecting her.[208] Priding herself on being "mere English",[209]Elizabeth trusted in God, honest advice, and the love of hersubjects for the success of her rule.[210] In a prayer, she offeredthanks to God that:

[At a time] when wars and seditions with grievous persecutions havevexed almost all kings and countries round about me, my reign hathbeen peacable, and my realm a receptacle to thy afflicted Church.The love of my people hath appeared firm, and the devices of myenemies frustrate.[204]

Ancestry

Family tree Thomas Boleyn,

1st Earl of Wiltshire Elizabeth Howard Henry VII,

King of England Elizabeth

of York

Mary Boleyn Anne Boleyn Henry VIII,

King of England Margaret Mary

Catherine Carey Henry Carey,

1st Baron Hudson Elizabeth I,

Queen of England Mary I,

Queen of England Edward VI,

King of England James V,

King of Scots Margaret Douglas Frances Brandon

Catherine Carey Mary I,

Queen of Scots Henry Stuart,

Lord Darnley Jane Grey

James VI,

King of Scots

Ahnentafel[hide]

Ancestors of Elizabeth I of England

16. Owen Tudor

8. Edmund Tudor, 1st Earl of Richmond

17. Catherine of Valois

4. Henry VII of England

18. John Beaufort, 1st Duke of Somerset

9. Margaret Beaufort

19. Margaret Beauchamp of Bletso

2. Henry VIII of England

20. Richard Plantagenet, 3rd Duke of York

10. Edward IV of England

21. Cecily Neville

5. Elizabeth of York

22. Richard Woodville, 1st Earl Rivers

11. Elizabeth Woodville

23. Jacquetta of Luxembourg

1. Elizabeth I of England

24. Geoffrey Boleyn

12. William Boleyn

25. Anne Hoo

6. Thomas Boleyn, 1st Earl of Wiltshire

26. Thomas Butler, 7th Earl of Ormonde

13. Margaret Butler

27. Anne Hankford

3. Anne Boleyn

28. John Howard, 1st Duke of Norfolk

14. Thomas Howard, 2nd Duke of Norfolk

29. Catherine Moleyns

7. Elizabeth Howard

30. Frederick Tilney

15. Elizabeth Tilney

31. Elizabeth Cheney

See also

Early modern Britain

English Renaissance

Portraiture of Elizabeth I of England

Protestant Reformation

Royal Arms of England

Royal eponyms in Canada – Queen Elizabeth I

Royal Standards of England

Tudor period

Notes

^ "I mean to direct all my actions by good advice and counsel."Elizabeth's first speech as queen, Hatfield House, 20 November1558. Loades, 35.

^ a b Starkey Elizabeth: Woman, 5.

^ Neale, 386.

^ Somerset, 729.

^ Somerset, 4.

^ Loades, 3–5

^ Somerset, 4–5.

^ Loades, 6–7.

^ In the Act of July 1536, it was stated that Elizabeth was"illegitimate ... and utterly foreclosed, excluded and banned toclaim, challenge, or demand any inheritance as lawful heir...to[the King] by lineal descent". Somerset, 10.

^ Loades, 7–8.

^ Somerset, 11.

^ Richardson, 39–46.

^ Richardson, 56, 75–82, 136

^ Weir, Children of Henry VIII, 7.

^ Our knowledge of Elizabeth's schooling and precocity comeslargely from the memoirs of Roger Ascham, also the tutor of PrinceEdward. Loades, 8–10.

^ Somerset, 25.

^ Loades, 21.

^ "Venice: April 1603", Calendar of State Papers Relating toEnglish Affairs in the Archives of Venice, Volume 9: 1592–1603(1897), 562–570. Retrieved 22 March 2012.

^ Stoyle, Mark. West Britons, Cornish Identities and the EarlyModern British State, University of Exeter Press, 2002, p220.

^ Davenport, 32.

^ a b Loades, 11.

^ Starkey Elizabeth: Apprenticeship, p. 69

^ Loades, 14.

^ Haigh, 8.

^ Neale, 32.

^ Williams Elizabeth, 24.

^ Loades, 14, 16.

^ a b Neale, 33.

^ Elizabeth had assembled 2,000 horsemen, "a remarkable tribute tothe size of her affinity". Loades 24–25.

^ Loades, 27.

^ Neale, 45.

^ Loades, 28.

^ Somerset, 51.

^ Loades, 29.

^ "The wives of Wycombe passed cake and wafers to her until herlitter became so burdened that she had to beg them to stop." Neale,49.

^ Loades, 32.

^ Somerset, 66.

^ Neale, 53.

^ Loades, 33.

^ Neale, 59.

^ Kantorowicz, ix

^ Full document reproduced by Loades, 36–37.

^ Somerset, 89–90. The "Festival Book" account, from the BritishLibrary

^ Neale, 70.

^ Patrick Collinson, "Elizabeth I (1533–1603)" in Oxford Dictionaryof National Biography (2008) accessed 23 Aug 2011

^ Lee, Christopher (1995, 1998). "Disc 1". This Sceptred Isle1547–1660. ISBN 978-0-563-55769-2.

^ Loades, 46.

^ "It was fortunate that ten out of twenty-six bishoprics werevacant, for of late there had been a high rate of mortality amongthe episcopate, and a fever had conveniently carried off Mary'sArchbishop of Canterbury, Reginald Pole, less than twenty-fourhours after her own death". Somerset, 98.

^ "There were no less than ten sees unrepresented through death orillness and the carelessness of 'the accursed cardinal' [Pole]".Black, 10.

^ Somerset, 101–103.

^ "Stamp-sized Elizabeth I miniatures to fetch ₤80.000", DailyTelegraph, 17 November 2009 Retrieved 16 May 2010

^ Loades, 38.

^ Haigh, 19.

^ Loades, 39.

^ Retha Warnicke, "Why Elizabeth I Never Married," History Review,Sept 2010, Issue 67, pp 15–20

^ a b Starkey Elizabeth: Woman, 5.

^ Neale, 386.

^ Somerset, 729.

^ Somerset, 4.

^ Loades, 3–5

^ Somerset, 4–5.

^ Loades, 6–7.

^ In the Act of July 1536, it was stated that Elizabeth was"illegitimate ... and utterly foreclosed, excluded and banned toclaim, challenge, or demand any inheritance as lawful heir...to[the King] by lineal descent". Somerset, 10.

^ Loades, 7–8.

^ Somerset, 11.

^ Richardson, 39–46.

^ Richardson, 56, 75–82, 136

^ Weir, Children of Henry VIII, 7.

^ Our knowledge of Elizabeth's schooling and precocity comeslargely from the memoirs of Roger Ascham, also the tutor of PrinceEdward. Loades, 8–10.

^ Somerset, 25.

^ Loades, 21.

^ "Venice: April 1603", Calendar of State Papers Relating toEnglish Affairs in the Archives of Venice, Volume 9: 1592–1603(1897), 562–570. Retrieved 22 March 2012.

^ Stoyle, Mark. West Britons, Cornish Identities and the EarlyModern British State, University of Exeter Press, 2002, p220.

^ Davenport, 32.

^ a b Loades, 11.

^ Starkey Elizabeth: Apprenticeship, p. 69

^ Loades, 14.

^ Haigh, 8.

^ Neale, 32.

^ Williams Elizabeth, 24.

^ Loades, 14, 16.

^ a b Neale, 33.

^ Elizabeth had assembled 2,000 horsemen, "a remarkable tribute tothe size of her affinity". Loades 24–25.

^ Loades, 27.

^ Neale, 45.

^ Loades, 28.

^ Somerset, 51.

^ Loades, 29.

^ "The wives of Wycombe passed cake and wafers to her until herlitter became so burdened that she had to beg them to stop." Neale,49.

^ Loades, 32.

^ Somerset, 66.

^ Neale, 53.

^ Loades, 33.

^ Neale, 59.

^ Kantorowicz, ix

^ Full document reproduced by Loades, 36–37.

^ Somerset, 89–90. The "Festival Book" account, from the BritishLibrary

^ Neale, 70.

^ Patrick Collinson, "Elizabeth I (1533–1603)" in Oxford Dictionaryof National Biography (2008) accessed 23 Aug 2011

^ Lee, Christopher (1995, 1998). "Disc 1". This Sceptred Isle1547–1660. ISBN 978-0-563-55769-2.

^ Loades, 46.

^ "It was fortunate that ten out of twenty-six bishoprics werevacant, for of late there had been a high rate of mortality amongthe episcopate, and a fever had conveniently carried off Mary'sArchbishop of Canterbury, Reginald Pole, less than twenty-fourhours after her own death". Somerset, 98.

^ "There were no less than ten sees unrepresented through death orillness and the carelessness of 'the accursed cardinal' [Pole]".Black, 10.

^ Somerset, 101–103.

^ "Stamp-sized Elizabeth I miniatures to fetch ₤80.000", DailyTelegraph, 17 November 2009 Retrieved 16 May 2010

^ Loades, 38.

^ Haigh, 19.

^ Loades, 39.

^ Retha Warnicke, "Why Elizabeth I Never Married," History Review,Sept 2010, Issue 67, pp 15–20

^ Loades, 42; Wilson, 95

^ Wilson, 95

^ Skidmore, 162, 165, 166–168

^ Chamberlin, 118

^ Somerset, 166–167. Most modern historians have considered murderunlikely; breast cancer and suicide being the most widely acceptedexplanations (Doran Monarchy, 44). The coroner's report, hithertobelieved lost, came to light in The National Archives in the late2000s and is compatible with a downstairs fall as well as otherviolence (Skidmore, 230–233).

^ Wilson, 126–128

^ Doran Monarchy, 45

^ Doran Monarchy, 212.

^ Adams, 384, 146.

^ Jenkins, 245, 247; Hammer, 46.

^ Doran Queen Elizabeth I, 61.

^ Wilson, 303.

^ Frieda, 397.

^ a b c Haigh, 17.

^ Loades, 53–54.

^ Loades, 54.

^ Somerset, 408.

^ Doran Monarchy, 87

^ Haigh, 20–21.

^ Haigh, 22–23.

^ Anna Dowdeswell (28 November 2007). "Historic painting is soldfor £2.6 million". bucksherald.co.uk. Retrieved 17 December2008..

^ John N. King, "Queen Elizabeth I: Representations of the VirginQueen," Renaissance Quarterly Vol. 43, No. 1 (Spring, 1990), pp.30–74 in JSTOR

^ Haigh, 23.

^ Susan Doran, "Juno Versus Diana: The Treatment of Elizabeth I'sMarriage in Plays and Entertainments, 1561–1581," HistoricalJournal 38 (1995): 257–74 in JSTOR

^ Haigh, 24.

^ Haigh, 131.

^ Mary's position as heir derived from her great-grandfather HenryVII of England, through his daughter Margaret Tudor. In her ownwords, "I am the nearest kinswoman she hath, being both of us ofone house and stock, the Queen my good sister coming of thebrother, and I of the sister". Guy, 115.

^ On Elizabeth's accession, Mary's Guise relatives had pronouncedher Queen of England and had the English arms emblazoned with thoseof Scotland and France on her plate and furniture. Guy,96–97.

^ By the terms of the treaty, both British and French troopswithdrew from Scotland. Haigh, 132.

^ Loades, 67.

^ Loades, 68.

^ Simon Adams: "Dudley, Robert, earl of Leicester (1532/3–1588)"Oxford Dictionary of National Biography online edn. May 2008(subscription required) Retrieved 3 April 2010

^ Letter to Mary, Queen of Scots, 23 June 1567." Quoted by Loades,69–70.

^ Loades, 72–73.

^ Loades, 73

^ Williams Norfolk, p. 174

^ a b McGrath, 69

^ a b c Collinson p. 67

^ Collinson pp. 67–68

^ Collinson p. 68

^ Loades, 73.

^ Guy, 483–484.

^ Loades, 78–79.

^ Guy, 1–11.

^ Frieda, 191.

^ a b Loades, 61.

^ Flynn and Spence, 126–128.

^ Somerset, 607–611.

^ a b Haigh, 135.

^ Strong and van Dorsten, 20–26

^ Strong and van Dorsten, 43

^ Strong and van Dorsten, 72

^ Strong and van Dorsten, 50

^ Letter to Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester, 10 February 1586,delivered by Sir Thomas Heneage. Loades, 94.

^ Chamberlin, 263–264

^ Elizabeth's ambassador in France was actively misleading her asto the true intentions of the Spanish king, who only tried to buytime for his great assault upon England: Parker, 193.

^ a b Starkey Elizabeth: Woman, 5.

^ Neale, 386.

^ Somerset, 729.

^ Somerset, 4.

^ Loades, 3–5

^ Somerset, 4–5.

^ Loades, 6–7.

^ In the Act of July 1536, it was stated that Elizabeth was"illegitimate ... and utterly foreclosed, excluded and banned toclaim, challenge, or demand any inheritance as lawful heir...to[the King] by lineal descent". Somerset, 10.

^ Loades, 7–8.

^ Somerset, 11.

^ Richardson, 39–46.

^ Richardson, 56, 75–82, 136

^ Weir, Children of Henry VIII, 7.

^ Our knowledge of Elizabeth's schooling and precocity comeslargely from the memoirs of Roger Ascham, also the tutor of PrinceEdward. Loades, 8–10.

^ Somerset, 25.

^ Loades, 21.

^ "Venice: April 1603", Calendar of State Papers Relating toEnglish Affairs in the Archives of Venice, Volume 9: 1592–1603(1897), 562–570. Retrieved 22 March 2012.

^ Stoyle, Mark. West Britons, Cornish Identities and the EarlyModern British State, University of Exeter Press, 2002, p220.

^ Davenport, 32.

^ a b Loades, 11.

^ Starkey Elizabeth: Apprenticeship, p. 69

^ Loades, 14.

^ Haigh, 8.

^ Neale, 32.

^ Williams Elizabeth, 24.

^ Loades, 14, 16.

^ a b Neale, 33.

^ Elizabeth had assembled 2,000 horsemen, "a remarkable tribute tothe size of her affinity". Loades 24–25.

^ Loades, 27.

^ Neale, 45.

^ Loades, 28.

^ Somerset, 51.

^ Loades, 29.

^ "The wives of Wycombe passed cake and wafers to her until herlitter became so burdened that she had to beg them to stop." Neale,49.

^ Loades, 32.

^ Somerset, 66.

^ Neale, 53.

^ Loades, 33.

^ Neale, 59.

^ Kantorowicz, ix

^ Full document reproduced by Loades, 36–37.

^ Somerset, 89–90. The "Festival Book" account, from the BritishLibrary

^ Neale, 70.

^ Patrick Collinson, "Elizabeth I (1533–1603)" in Oxford Dictionaryof National Biography (2008) accessed 23 Aug 2011

^ Lee, Christopher (1995, 1998). "Disc 1". This Sceptred Isle1547–1660. ISBN 978-0-563-55769-2.

^ Loades, 46.

^ "It was fortunate that ten out of twenty-six bishoprics werevacant, for of late there had been a high rate of mortality amongthe episcopate, and a fever had conveniently carried off Mary'sArchbishop of Canterbury, Reginald Pole, less than twenty-fourhours after her own death". Somerset, 98.

^ "There were no less than ten sees unrepresented through death orillness and the carelessness of 'the accursed cardinal' [Pole]".Black, 10.

^ Somerset, 101–103.

^ "Stamp-sized Elizabeth I miniatures to fetch ₤80.000", DailyTelegraph, 17 November 2009 Retrieved 16 May 2010

^ Loades, 38.

^ Haigh, 19.

^ Loades, 39.