Literature Network» Anton Chekhov» TheBeggar

主题:[原创]看透装在套子里的契诃夫

contemptible[英][kənˈtemptəbəl][美][kənˈtɛmptəbəl]

adj.<正>可轻蔑的,可鄙的,卑劣的

swindle[英][ˈswɪndl][美][ˈswɪndl]

vt.诈骗,骗取;欺骗,诓骗

n.诈骗,骗取;骗局;冒牌货,冒名顶替者

pothouse 中文 n. 小酒馆,小旅馆

billiard-marker 中文n. 台球记分员(或记分器)genteel[英][dʒenˈti:l][美][dʒɛnˈtil]

adj.文雅的;有礼貌的;有教养的;上流社会的

justification[英][ˌdʒʌstifiˈkeiʃən][美][ˌdʒʌstəfɪˈkeʃən]

n.辩解;无过失;正当的理由

demeanour[英][dɪˈmi:nə][美][dɪˈminɚ]

n.<正>行为;举止;态度;动作

notary[英][ˈnəʊtəri:][美][ˈnotəri]

n.公证人,公证员

rectitude[英][ˈrektɪˌtu:d, -ˌtju:d][美][ˈrɛktɪˌtud,-ˌtjud]n.操行端正;笔直

genially[英][ˈdʒi:njəlɪ][美][ˈdʒinjəlɪ]

adv.亲切地,和蔼地;快活地

disincline[英][ˈdisinˈklain][美][ˌdɪsɪnˈklaɪn]vt.使讨厌,不感兴趣

topple[英][ˈtɔpl][美][ˈtɑpəl]vi.倾倒;摇摇欲坠;倾斜得好倾斜得好像要跌倒一样

vt.将…推翻,打倒;使…跌倒

自尊 amour-propre 自爱; 自尊; 虚荣心; 自尊心

- 1. Appreciate those whodisdained you, becausehe awakedyour amour -propre .

- 感激蔑视你的人, 因为他觉醒了你的 自尊.

来自互联网

- 2. I wounded her amour - propre .

- 我伤了她的 自尊心.

来自互联网

- 3. Try not to offendhis amourpropre.

- 尽量别伤他自尊心.

来自互联网

- 4. Absolutely , secondone can satisfy my amour - propre.

- 显然后面这个可以满足我的虚荣心.

来自互联网

- 5. I'm sorry foryour sakethat Ihad nohopeless amour.

- 为了你的缘故,我感到遗憾的是,我不曾有过那种毫无希望的不正当男女关系.

来自辞典例句

- 6. Have you heard about his latest amour?

- 你听说他最近偷情的事了 吗 ?

来自辞典例句

- 7. La femme commencepar aimer un homme et finit par aimerl'amour.

- 女人以爱一个男人开始,以爱爱情终止.

来自互联网

- 8. L'homme commence paraimer l'amour et finitpar aimerla femme.

- 男人以爱爱情开始,以爱女人结束.

来自互联网

- 9. Plaisir d'amour ne durequ'un moment, chagrin d'amour duretoute la vie.

- 爱的快乐只存在一时, 而爱的悲伤却残留一世.

来自互联网

- 10. Un jour l'Amour dit à l'Amiti é: Mais à quoi tu sers toi?

- 一天爱情问友情: 你是干吗用的?

justification[英][ˌdʒʌstifiˈkeiʃən][美][ˌdʒʌstəfɪˈkeʃən]

n.辩解;无过失;正当的理由

shopman[ˈʃɔpmən]n.店主,店员;(修理店中的)修理工

malignant[英][məˈliɡnənt][美][məˈlɪɡnənt]

adj.恶性的,致命的;恶意的,恶毒的

n.怀有恶意的人;<英史>保王党员

demeanour[英][dɪˈmi:nə][美][dɪˈminɚ]

n.<正>行为;举止;态度;动作

"KIND sir, be so good as to notice a poor, hungry man. I have nottasted food for three days. I have not a five-kopeck piece for anight's lodging. I swear by God! For five years I was a villageschoolmaster and lost my post through the intriguesof the Zemstvo. I was the victim of falsewitness. I have been out of a place for a year now."Skvortsov, a Petersburg lawyer, looked at the speaker's tattereddark blue overcoat, at his muddy, drunken eyes, at the red patcheson his cheeks, and it seemed to him that he had seen the manbefore.

"And now I am offered a post in the Kaluga province," the beggarcontinued, "but I have not the means for the journey there.Graciously help me! I am ashamed to ask, but . . . I amcompelled by circumstances."

Skvortsov looked at his goloshes, of which one was shallow like ashoe, while the other came high up the leg like a boot, andsuddenly remembered.

"Listen, the day before yesterday I met you in Sadovoy Street," hesaid, "and then you told me, not that you were a villageschoolmaster, but that you were a student who had been expelled. Doyou remember?"

"N-o. No, that cannot be so!" the beggar muttered in confusion. "Iam a village schoolmaster, and if you wish it I can show youdocuments to prove it."

"That's enough lies! You called yourself a student, and even toldme what you were expelled for. Do you remember?"

Skvortsov flushed, and with a look of disgust on his face turnedaway from the ragged figure.

"It's contemptible, sir!" he cried angrily. "It'sa swindle! I'll hand you over to the police, damnyou! You are poor and hungry, but that does not give you the rightto lie so shamelessly!"

contemptible[英][kənˈtemptəbəl][美][kənˈtɛmptəbəl]

adj.<正>可轻蔑的,可鄙的,卑劣的

swindle[英][ˈswɪndl][美][ˈswɪndl]

vt.诈骗,骗取;欺骗,诓骗

n.诈骗,骗取;骗局;冒牌货,冒名顶替者

The ragged figure took hold of the door-handle and, like a bird ina snare, looked round the hall desperately.

"I . . . I am not lying," he muttered. "I can showdocuments."

"Who can believe you?" Skvortsov went on, still indignant. "Toexploit the sympathy of the public for villageschoolmasters and students -- it's so low, so mean, sodirty! It's revolting!"

Skvortsov flew into a rage and gave the beggar a mercilessscolding. The ragged fellow's insolent lyingaroused his disgust and aversion, was an offenceagainst what he, Skvortsov, loved and prized in himself:kindliness, a feeling heart, sympathy for the unhappy. By hislying, by his treacherous assault upon compassion,the individual had, as it were, defiled thecharity which he liked to give to the poor with nomisgivings in his heart. The beggar at first defendedhimself, protested with oaths, then he sank intosilence and hung his head, overcome withshame.

"Sir!" he said, laying his hand on his heart, "I really was . . .lying! I am not a student and not a village schoolmaster.All that's mere invention! I used to be in theRussian choir, and I was turned out of it for drunkenness. But whatcan I do? Believe me, in God's name, I can't get on without lying-- when I tell the truth no one will give me anything. With thetruth one may die of hunger and freeze without anight's lodging! What you say is true, I understand that, but . . .what am I to do?"

"What are you to do? You ask what are you to do?" cried Skvortsov,going close up to him. "Work -- that's what you must do! You mustwork!"

"Work. . . . I know that myself, but where can I get work?"

"Nonsense. You are young, strong, and healthy, and could alwaysfind work if you wanted to. But you know you are lazy,pampered, drunken! You reek ofvodka like a pothouse! You have becomefalse and corrupt to the marrow of your bones andfit for nothing but begging and lying! If you do graciouslycondescend to take work, you must have a job in anoffice, in the Russian choir, or as abilliard-marker, where you will have a salary andhave nothing to do! But how would you like to undertakemanual labour? I'll be bound, youwouldn't be a house porter or a factory hand! Youare too genteel for that!"

pothouse 中文 n. 小酒馆,小旅馆billiard-marker 中文n. 台球记分员(或记分器)

genteel[英][dʒenˈti:l][美][dʒɛnˈtil]

adj.文雅的;有礼貌的;有教养的;上流社会的

"What things you say, really . . ." said the beggar, and he gave abitter smile. "How can I get manual work? It's rather late for meto be a shopman, for in trade one has to beginfrom a boy; no one would take me as a house porter, because I amnot of that class. . . . And I could not get work in a factory; onemust know a trade, and I know nothing."

shopman[ˈʃɔpmən]

n.店主,店员;(修理店中的)修理工

"Nonsense! You always find some justification!Wouldn't you like to chop wood?"

justification[英][ˌdʒʌstifiˈkeiʃən][美][ˌdʒʌstəfɪˈkeʃən]

n.辩解;无过失;正当的理由

demeanour[英][dɪˈmi:nə][美][dɪˈminɚ]

n.<正>行为;举止;态度;动作

"I would not refuse to, but the regular woodchoppers are out ofwork now.""Oh, all idlers argue like that! As soon as you are offeredanything you refuse it. Would you care to chop wood for me?"

"Certainly I will. . ."

"Very good, we shall see. . . . Excellent. We'll see!" Skvortsov,in nervous haste; and not withoutmalignant pleasure, rubbing his hands, summonedhis cook from the kitchen.

malignant[英][məˈliɡnənt][美][məˈlɪɡnənt]

adj.恶性的,致命的;恶意的,恶毒的

n.怀有恶意的人;<英史>保王党员

"Here, Olga," he said to her, "take this gentleman to the shed andlet him chop some wood."

The beggar shrugged his shoulders as though puzzled, andirresolutely followed the cook. It was evident from hisdemeanour that he had consented to go and chop wood, notbecause he was hungry and wanted to earn money, but simply fromshame and amour propre, because he had been takenat his word. It was clear, too, that he was suffering from theeffects of vodka, that he was unwell, and felt not thefaintest inclination to work.

demeanour[英][dɪˈmi:nə][美][dɪˈminɚ]

n.<正>行为;举止;态度;动作

自尊 amour-propre 自爱; 自尊; 虚荣心; 自尊心- 1. Appreciate those whodisdained you, becausehe awakedyour amour - propre .

- 感激蔑视你的人, 因为他觉醒了你的 自尊.

来自互联网

- 2. I wounded her amour -propre .

- 我伤了她的 自尊心.

来自互联网

- 3. Try not to offendhis amour propre.

- 尽量别伤他自尊心.

来自互联网

- 4. Absolutely , second onecan satisfymy amour - propre.

- 显然后面这个可以满足我的虚荣心.

来自互联网

- 5. I'm sorry foryour sakethat Ihad nohopeless amour.

- 为了你的缘故,我感到遗憾的是,我不曾有过那种毫无希望的不正当男女关系.

来自辞典例句

- 6. Have you heard about his latest amour?

- 你听说他最近偷情的事了 吗 ?

来自辞典例句

- 7. La femme commence paraimer un homme et finit par aimerl'amour.

- 女人以爱一个男人开始,以爱爱情终止.

来自互联网

- 8. L'homme commence paraimer l'amour et finitpar aimerla femme.

- 男人以爱爱情开始,以爱女人结束.

来自互联网

- 9. Plaisir d'amourne dure qu'un moment, chagrin d'amour duretoute la vie.

- 爱的快乐只存在一时, 而爱的悲伤却残留一世.

来自互联网

- 10. Un jour l'Amour dit à l'Amiti é: Mais à quoi tu sers toi?

- 一天爱情问友情: 你是干吗用的?

Skvortsov hurried into the dining-room. There from the window whichlooked out into the yard he could see the woodshed and everythingthat happened in the yard. Standing at the window, Skvortsov sawthe cook and the beggar come by the back way into the yard and gothrough the muddy snow to the woodshed. Olga scrutinized hercompanion angrily, and jerking her elbow unlocked the woodshed andangrily banged the door open.

"Most likely we interrupted the woman drinking her coffee," thoughtSkvortsov. "What a cross creature she is! "

Then he saw the pseudo-schoolmaster andpseudo-student seat himself on a block of wood, and,leaning his red cheeks upon his fists, sink into thought. The cookflung an axe at his feet, spat angrily on the ground, and, judgingby the expression of her lips, began abusing him. The beggar drew alog of wood towards him irresolutely, set it up between his feet,and diffidently drew the axe across it. The logtoppled and fell over. The beggar drew it towardshim, breathed on his frozen hands, and again drew the axe along itas cautiously as though he were afraid of its hitting his golosh orchopping off his fingers. The log fell overagain.topple[英][ˈtɔpl][美][ˈtɑpəl]

vi.倾倒;摇摇欲坠;倾斜得好倾斜得好像要跌倒一样

vt.将…推翻,打倒;使…跌倒

Skvortsov's wrath had passed off by now, he felt sore and ashamedat the thought that he had forced a pampered, drunken, and perhapssick man to do hard, rough work in the cold.

"Never mind, let him go on . . ." he thought, going from thedining-room into his study. "I am doing it for his good!"

An hour later Olga appeared and announced that the wood had beenchopped up.

"Here, give him half a rouble," said Skvortsov. "If he likes, lethim come and chop wood on the first of every month. . . . Therewill always be work for him."

On the first of the month the beggar turned up and again earnedhalf a rouble, though he could hardly stand. From that timeforward he took to turning up frequently, and work wasalways found for him: sometimes he would sweep the snow into heaps,or clear up the shed, at another he used to beat the rugs and themattresses. He always received thirty to forty kopecks for hiswork, and on one occasion an old pair of trousers was sent out tohim.

When he moved, Skvortsov engaged him to assist in packing andmoving the furniture. On this occasion the beggar was sober,gloomy, and silent; he scarcely touched the furniture, walked withhanging head behind the furniture vans, and did not even try toappear busy; he merely shivered with the cold, and was overcomewith confusion when the men with the vans laughed at his idleness,feebleness, and ragged coat that had once been a gentleman's. Afterthe removal Skvortsov sent for him.

"Well, I see my words have had an effect upon you," he said, givinghim a rouble. "This is for your work. I see that you are sober andnot disinclined to work. What is yourname?"disincline[英][ˈdisinˈklain][美][ˌdɪsɪnˈklaɪn]

vt.使讨厌,不感兴趣

"Lushkov."

"I can offer you better work, not so rough, Lushkov. Can youwrite?"

"Yes, sir."

"Then go with this note to-morrow to my colleague and he will giveyou some copying to do. Work, don't drink, and don't forget what Isaid to you. Good-bye."

Skvortsov, pleased that he had put a man in the path ofrectitude, patted Lushkov genially on theshoulder, and even shook hands with him atparting.rectitude[英][ˈrektɪˌtu:d,-ˌtju:d][美][ˈrɛktɪˌtud,-ˌtjud]

n.操行端正;笔直

genially[英][ˈdʒi:njəlɪ][美][ˈdʒinjəlɪ]

adv.亲切地,和蔼地;快活地

Lushkov took the letter, departed, and from that time forward didnot come to the back-yard for work.

Two years passed. One day as Skvortsov was standing at theticket-office of a theatre, paying for his ticket, he saw besidehim a little man with a lambskin collar and a shabby cat's-skincap. The man timidly asked the clerk for a gallery ticket and paidfor it with kopecks.

"Lushkov, is it you?" asked Skvortsov, recognizing in the littleman his former woodchopper. "Well, what are you doing? Are yougetting on all right?"

"Pretty well. . . . I am in a notary's office now.I earn thirty-five roubles."notary[英][ˈnəʊtəri:][美][ˈnotəri]

n.公证人,公证员

"Well, thank God, that's capital. I rejoice foryou. I am very, very glad, Lushkov. You know, in a way, you are mygodson. It was I who shoved you into the rightway. Do you remember what a scolding I gave you, eh? Youalmost sank through the floor that time. Well, thank you, my dearfellow, for remembering my words."

"Thank you too," said Lushkov. "If I had not come to you that day,maybe I should be calling myself a schoolmaster or a student still.Yes, in your house I was saved, and climbed out of the pit."

"I am very, very glad."

"Thank you for your kind words and deeds. What you said that daywas excellent. I am grateful to you and to your cook, God blessthat kind, noble-hearted woman. What you said that day wasexcellent; I am indebted to you as long as I live,of course, but it was your cook, Olga, who really saved me."

"How was that?"

"Why, it was like this. I used to come to you to chop wood and shewould begin: 'Ah, you drunkard! You God-forsakenman! And yet death does not take you!' and then she wouldsit opposite me, lamenting, looking into my face and wailing: 'Youunlucky fellow! You have no gladness in this world, and inthe next you will burn in hell, poor drunkard! You poorsorrowful creature!' and she always went on in that style, youknow. How often she upset herself, and how many tears she shed overme I can't tell you. But what affected me most -- she chopped thewood for me! Do you know, sir, I never chopped a single log for you-- she did it all! How it was she saved me, how it was I changed,looking at her, and gave up drinking, I can't explain. I only knowthat what she said and the noble way she behaved brought about achange in my soul, and I shall never forget it. It's time to go up,though, they are just going to ring the bell."

Lushkov bowed and went off to the gallery.

看透装在套子里的契诃夫

——谈契诃夫的现实主义

我们常把“批判现实主义”的外衣套到了契诃夫身上,且把离脖子最近的那粒政治风纪扣扣得紧而又紧。事实上这反而妨碍我们对他的理解,契诃夫的现实主义是广泛的、深刻的、复杂的,需要我们看透套子,看清套中渊博的契诃夫。

契诃夫像一条平静的河流,生活的苦痛是那浅绿色和水上的涟漪,而河水流动本身就是善良和同情的象征。我们置身于这些河流,如同躺在水底的枯枝败叶,望着水面,望着天空,度过一生,被推向安详而平静的归宿。

跨越了一百年,人们依然在这条河流里憧憬,失望,空谈,等待,由于欲望和过失痛苦的生活着。

一般来讲,提到“现实主义”,人们就往往有一种血淋淋、惨不忍卒的残酷感,而我们读契诃夫小说却并不如此。尽管契诃夫也是以批判现实主义为创作宗旨的作家,但他笔下的种种人物、故事,不论是《胖子和瘦子》、《一个官员之死》、《变色龙》、《跳来跳去的女人》,还是《草原》、《第六病室》、《我的一生》、《新娘》、《文学教师》等作品,无不给人以憎恶或笑、却又不让人感到绝望失落的感觉,反而振奋人们更加积极进取,对生活充满信心和勇气的力量。总而言之,契诃夫的小说在艺术性和思想性的完美结合上达到了一个后人难以企及的高度,既具有清新朴实之风骨而又极富批判现实之意义,在整个世界文坛可称得上是别具匠心、独树一帜。这也是高尔基评论他的小说“正在扼杀现实主义”的原因所在。

以《樱桃园》为例,《樱桃园》是契诃夫的绝笔,描写了19世纪末20世纪初,俄国资本主义迅速发展、贵族庄园彻底崩溃的情景。他写《樱桃园》时已是肺病晚期,如果好好休养,生命也许还可以延长几年,但观众们热切等待着他的新作,他不得不全力赶稿。1904年1月17日,由斯坦尼斯拉夫斯基亲自执导的《樱桃园》在莫斯科艺术剧院成功首演,主演则是契诃夫的夫人克尼碧尔。然而半年后,契诃夫就离开了人世。所以,《樱桃园》一直被视做契诃夫戏剧的最后巅峰。

“樱桃园,这是一个美妙的名字。”契诃夫对他的合作伙伴,莫斯科艺术剧院的导演斯坦尼斯拉夫斯基这么说过。这部话剧是契诃夫一生中最心爱的一部,甚至说起它的名字,他都禁不住压低了声音。

契诃夫把这部以变化与失去为主题的深邃而诗意的话剧叫作喜剧,“有些地方甚至是闹剧。”他坚决反对斯坦尼斯拉夫斯基含泪的,伤感的,过于现实主义的阐释。他反复强调这部戏的核心“是笑,而不是泪。”

《樱桃园》诞生的时代,俄国正处在社会急剧转型中,使得契诃夫的戏剧负荷了那个大变动时代的悲欢离合与爱恨情仇。契诃夫不像托尔斯泰要主张什么,也不像高尔基要打倒什么,只是客观地、温和地记录下那些形形色色的人物:没落的贵族、过气的演员、寂寞的医生、负债的小地主、消沉的知识分子、总也毕不了业的大学生,以及那些可笑的、可悯的、善良的小人物。他们的生活漫无目的:在那个时代的洪流里,沙皇都不能自保,整个社会都将沉沦,谁又能自诩是自己生命的舵手呢?

俄国作家米哈尔科夫说:“契诃夫的惊人天才在于,当他讲自己的时候,我们仿佛觉得这也是在说我们。”高尔基说,这就是契诃夫作品“最可怕的力量”。

契诃夫的戏剧作品色彩丰富多变,以至于人们难以判定它们是悲剧还是喜剧。作品基本上都曲折反映了俄国1905年大革命前夕一部分小资产阶级知识分子的苦闷和追求,含有浓郁的抒情味和丰富的潜台词,令人回味无穷。

论家别雷出于象征派理论的需要,提出了“木已非木”及“多样性奥秘的集合”的观点。在契诃夫的作品中,的确存在许多似是而非的东西及多种秘密的复合,但这是由生活本身的复杂

性造成的,在矛盾及奥秘的后面有着一个极其清晰的头脑。我个人认为,在绝大多数情况下,“细胞”的意义并没有滑离,它像基因一样把它的密码藏在了细胞的内部。契诃夫的“细胞”所包含的东西远远超出了它本身的容量和体积。他的笔触是轻盈机敏的,他的夸张由于常在微观的层次上进行,因而不太引人注目。这些丝毫也不特殊的“细胞”却能够震撼读者的心灵,或者强度虽然不大,但具有持久的感染力。他熟悉并善于调动幽默的一切手段,常常把幽默与悲剧性同时偷运到“细胞”里。在他的优秀作品里,随着时间的推移,他的幽默与讽刺会使悲剧性变得越来越强烈,甚至可能会像原子的链式反应一样达到爆炸的程度。他有着不逊于古希腊人的命运感,但在他那里,站在俄底甫斯国王身后的合唱队,不是从血腥的情节里,而是从具有两种成分的“细胞”里发出声音来。罗丹曾依据但丁的《神曲》雕刻过一件名为《地狱之门》的作品,让那些在地狱里备受煎熬的人们攀附在“地狱之门”上;一个作家若要使其人物也攀附在“地狱之门”上,通常是必须依靠大手段的,但契诃夫却是用小手段做到这一点的作家。

在阶级斗争学说尚未兴起的年代,小说《新别墅》竟然成了“生动地描绘”地主与农民冲突的作品。在他死了50年后,小说《在朋友家里》与剧作《樱桃园》依然被叶尔米洛夫看作是富有“诗意”的作品,这位研究了20多年的契诃夫专家因此获得了1950年的斯大林奖金。对于中篇小说《灯光》及《我的一生》,批评界最初的反应是一片沉默;对于契诃夫不想被删改一个字的《主教》,则用几句无关痛痒的话打发掉了。可能就连他本人也对能否真正被理解丧失了信心:“我实际上是孤独地活在世上,正如我将孤独地躺在坟墓中一样。”后半句话表明,他认为将来也不会被理解。

事实证明,这一回却是他错了。他的小说首先在英国、继而在美国得到了惊人的好评。女作家曼斯菲尔德愿意用莫泊桑的小说全集去换取契诃夫的一个短篇。刨去英国人与法国人之间的恩怨因素,这也是一个绝对出乎预料的评价。毛姆则认为,“今天,在最好的评论家的心目中,没有一个人的小说占有比契诃夫更高的位置。”作为小说家的契诃夫这一回超过的是作为戏剧大师的契诃夫。据周启超在《世界文学》1998年第5期中的介绍,近些年来,契诃夫作品中的一些非现实主义的因素,在俄罗斯受到了空前热烈的关注。

绝望没关系,一切都会过去的

在最近的“契诃夫学”著作中,有学者俨然声称:契诃夫乃是20世纪的作家,但没有这个世纪时髦的风尚;乃是一个象征主义者,但没有这个流派的宣言及其在塔上的彻夜祈祷;乃是一个先知,但没有那种辞藻华丽的预言。

在俄语布克奖连续3年颁给后现代派作家的90年代,契诃夫的声誉依然有着足够的攀升及反弹空间,这岂不是一件咄咄怪事?

一位很有抱负的年轻作家在电话中说他感到绝望,这时我便想起了《大沃洛嘉和小沃洛嘉》的结尾。即便是在现实中,契诃夫也是有用的,他至少使我可以握紧话筒,学着奥丽雅安慰利沃夫娜的腔调说话:这些都没关系,一切都会过去的……

尽管伟大的契诃夫通常是指《草原》以后的契诃夫,但翻译家汝龙仍然不辞劳苦地把《草原》以前的作品翻译了出来,这部分作品在《契诃夫小说全集》中占了一大半的篇幅(其中的许多作品依然是杰作)。在本文行将结束时,我觉得有必要用黑体字向汝龙先生表示敬意,我想每一个喜爱契诃夫的人大概都会赞同我的做法的。在五六个人用三四个星期竞相“移译”的时代,不这样做才是有失公平的。

“没有人像安东·契诃夫那样透彻地、敏锐地了解生活琐碎卑微的悲剧性,在他以前还从没有人能够把人们生活的那幅可耻、可厌的图画,照它在小市民日常生活中的毫无生气的混乱样子,极其真实地描绘给他们看。”高尔基说。

但这是高尔基所理解的那部分契诃夫,他把这个局部契诃夫用到了他自己的作品中。在他的自传体小说中,他按照生活“毫无生气的混乱样子”,为我们“极其真实地”描绘了他那个时代的俄国,那个时代的底层社会。在高尔基的画面中,有踏坏的道路,龌龊的房屋,有使读者的心为之抽紧的那种悲惨,但不会有悲剧的利箭突然冲我们的前额射来。这是他们两人的差别,其相距之远,犹如天壤。据安德列·别雷的看法,在修辞与文体方面,他们之间亦有天壤之别。

契诃夫在一封信中阐述了自己的小说原则:“我们必须写简单的事情:比如塞米诺维奇怎样和伊凡诺夫娜结婚了,就是这样。”他排除了在这两个普普通通的人结婚时,第三个人从钟楼上跳下来的可能。这也许可以归结为:契诃夫摈弃了基于情节巧合的戏剧性。

在相当长时间里,在世界舞台上人们似乎将契诃夫遗忘掉了。然而,国际戏剧界突然惊讶地发现契诃夫穿越时空、记录了人类永恒困惑的价值后,契诃夫成为继莎士比亚后世界戏剧的又一座丰碑。在欧美戏剧繁荣的国家,“没有一年不演契诃夫,就像不可能不演莎士比亚一样”。事实上,在欧洲和美国上演最多的经典剧作家中,莎士比亚无疑排名第一,而第二位则非契诃夫莫属。从上世纪70年代起,当今世界上最具盛名的戏剧大师布鲁克就将《樱桃园》与《哈姆莱特》一并作为自己的代表作,在全世界演出。这就意味着,一位最优秀的戏剧导演必定要同时与两位戏剧创作大师对话,一位是“传奇性戏剧”的“泰山”莎士比亚,另一位则是“散文性戏剧”的“北斗”契诃夫。

有文学评论家认为,契诃夫以自己的全部创作,肯定了一切平凡和普通的人,一切劳动者和创造者所应有的享受幸福的权利。契诃夫有一条札记说:“为公众福利服务的愿望,应该成为心灵的需要和个人幸福的条件。”

在契诃夫的小说、戏剧中,我们看到的往往是一些普通人平淡的日常生活。尽管文字包含着忧郁,流淌着哀愁,但结尾总是会暗示人们,不管生活当中发生了什么,生活并没有到此结束。

在今天,“小公务员”、“变色龙”、“套中人”等形象仍然能在全世界找到“对号入座”者,令人哀其不幸、怒其不争。提起契诃夫,人们自然会联想到给“天堂爷爷”寄信的小万卡,由于一个喷嚏溅到长官身上而郁郁而终的小公务员,因为一条狗而尽显奴颜婢膝本色的“变色龙”奥楚蔑洛夫,以及“套中人”别列科夫,他不仅力图把自己的身体、思想等藏到套子里,而且还力图将周围的一切都做上套子,直到他的雨鞋和雨伞……

俄国作家米哈尔科夫说:“契诃夫的惊人天才在于,当他讲自己的时候,我们仿佛觉得这也是在说我们。”高尔基说,这就是契诃夫作品“最可怕的力量”。

契诃夫作品风格独特,言简意赅,他的那句名言“天才的姊妹是简练”成为后世作家孜孜追求的座右铭。

契诃夫属于点石成金的匠人,寥寥几笔就能写活一个人一个物件,可这位工匠情绪上偏于苦闷偏于虚无,笔下的活物于是都半死不活地活着。所以,从这一点来说,造物主(或者说作家)的禀性实在太重要了,赶上一个反复无常的天神,我们只好在猜疑中度日。契诃夫比较宝贵的是他遇弱则弱,遇强则强的禀性。弱者从他仁慈的目光中得到安慰,强者被他刚性的思想吸引。他是一股无形的力,这种力量用一个名词来表示就是“无力”。梅列日科夫斯基曾借了高尔基的一段话,来点明契诃夫与高尔基二人的创作主旨:“因内在的软弱而万劫不复的社会,在它咽气之前将把我的书当成送终麝香。”他的文章是那样的灰暗,散发着精心提炼的香气。

在他的作品中,我们不仅看到了凡俗生活隐藏下的悲剧,也看到了含泪的微笑之下的希

望;不仅看到了极具质感的细微情节和情节之下的生活真相,也看到了真相之下埋藏的雄阔的历史轨迹和现实走向。正如有论者所说,契诃夫以自己的全部创作,肯定了一切平凡和普通的人、一切劳动者和创造者所应有的享受幸福的权利。在他的作品中,不是没有讽刺和鞭挞,不是没有批评和否定;俄罗斯诗人霍达谢维奇说:“起初他把他们表现为庸人,后来把他们表现为平常的人,对他们表示怜悯,再后来开始在他们身上寻找优点,最终对他们怀抱起巨大的爱。”契诃夫以巨大的爱的胸怀在包容理解着自己笔下的人物,他准确仔细地描绘着他们,同时在抒情诗的高度为他们的存在作了辩护。契诃夫怀着深厚的情感珍惜着自己笔下的人物,他对人类的生活寄予了这样的理想:“人的一切都应该是美丽的:无论是面孔,还是衣裳,还是心灵,还是思想。”

俄国作家米哈尔科夫洞悉到契诃夫作品中的人物和契诃夫自己的关系:“契诃夫的惊人天才在于,当他讲自己的时候,我们仿佛觉得这也是在说我们。他对自己笔下的人物有时很严厉,但从不把他写的人物和他自己分开。他能在每一个人身上发现他自己。”我们从契诃夫的作品中,似乎也感受到了鲁迅先生《一件小事》中的那种反观自我的自省和自剖。

契诃夫始终在为这样的一些问题所苦恼:“我为什么写作?我有用吗?我的文学创作的目的是什么?”在一个作家对这些貌似“常识”的坦诚自问背后,我们看到了一颗始终对社会、对人民朝警夕惕的高贵的内心。

契诃夫的创作口号是———“人和劳动”,在这样宏阔的思考背景之下,他的创作自然呈现出超越时代的意义。康·巴乌斯托夫斯基在《金蔷薇》里谈到契诃夫时,用了一个特殊的名词“契诃夫感”。他觉得现实的俄语中无法找到一个和契诃夫作品所表达的内涵相应的词汇,所以不得不用“契诃夫感”———这样一个充满深情的专有名词,来形容契诃夫那伟大而敏感的心灵所描绘的伟大而庄严的现实。我们从这一充满敬意的词汇中,仿佛也感受到了托尔斯泰、陀思妥耶夫斯基、鲁迅、老舍……那一脉相通的柔善而又谦卑的心灵。我们感受到的,是他们那永远谦卑而敏感的内心:他们的内心谦卑得和普通人一样高贵,他们的内心沉潜得和历史一样深旷;也只有这样谦卑而沉潜的内心,才能够真正感受到来自人民、

来自历史深处的大海潮汐的涌动。高尔基说:“一想到契诃夫,勇气马上就来了,生活也马上变成明确而富有意义了。这样的人是世界的‘轴’。”

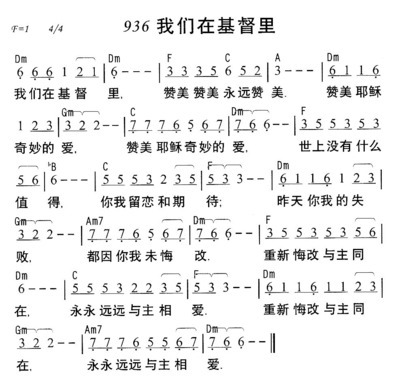

多么希望把所有契诃夫的作品都印在琴谱上,因为他的作品真的是一首唱不完的生命之歌。歌中有笑有泪,才是真正的契诃夫,而不再是那个被装在现实主义套子里的俄国作家。

爱华网

爱华网