http://thinkexist.com/quotes/michel_foucault/2.html

Power is not an institution, and not astructure; neither is it a certain strength we are endowed with; itis the name that one attributes to a complex strategicalsituation in a particular society.

The work of an intellectual is not to mould thepolitical will of others; it is, through the analyses that he doesin his own field, to re-examine evidence and assumptions,to shake up habitual ways of working and thinking, to dissipateconventional familiarities, to re-evaluate rules and institutionsand to participate in the formation of a political will(where he has his role as citizen to play).

The judges of normality are present everywhere.We are in the society of the teacher-judge, the doctor-judge, theeducator-judge, the "social worker" -judge.

In its function, the power to punish is not essentiallydifferent from that of curing or educating.

The strategic adversary is fascism... the fascism in us all, inour heads and in our everyday behavior, the fascism thatcauses us to love power, to desire the very thing that dominatesand exploits us.

What strikes me is the fact that in our society, art hasbecome something which is only related to objects, and not toindividuals, or to life.

As the archaeology of our thought easily shows, man isan invention of recent date. And one perhaps nearing itsend.

If repression has indeed been the fundamental link betweenpower, knowledge, and sexuality since the classical age, it standsto reason that we will not be able to free ourselves fromit except at a considerable cost.

There are more ideas on earth than intellectuals imagine. Andthese ideas are more active, stronger, more resistant, morepassionate than ''politicians'' think. We have to be there at thebirth of ideas, the bursting outward of their force: not in booksexpressing them, but in events manifesting this force, in strugglescarried on around ideas, for or against them. Ideas do notrule the world. But it is because the world has ideas... that it isnot passively ruled by those who are its leaders or those who wouldlike to teach it, once and for all, what it mustthink.

Freedom of conscience entails more dangers thanauthority and despotism.

http://www.egs.edu/library/michel-foucault/quotes/

Michel Foucault - Quotes

...a number of phenomena that seem to me to be quitesignificant, namely, the set of mechanisms through which the basicbiological features of the human species became the object of apolitical strategy, of a general strategy of power, or, in otherwords, how, starting from the eighteenth century, modern westernsocieties took on board the fundamental biological fact that humanbeings are a species. This is roughly what I have calledbiopower.

Foucault, Michel and Graham Burchell (Translator). Security,Territory, Population. 1977-78.Power is not founded on itself or generated by itself. Or wecould say, more simply, that there are not first of all relationsof production and then, in addition, alongside or on top of theserelations, mechanisms of power that modify or disturb them, or makethem more consistent, coherent, or stable.

Foucault, Michel and Graham Burchell (Translator). Security,Territory, Population. 1977-78.I think this serious and fundamental relation between struggleand truth, the dimension in which philosophy has developed forcenturies and centuries, only dramatizes itself, becomes emaciated,and loses its meaning and effectiveness in polemics withintheoretical discourse. So in all of this I will therefore proposeonly one imperative, but it will be categorical and unconditional:Never engage in polemics.

Foucault, Michel and Graham Burchell (Translator). Security,Territory, Population. 1977-78.When one undertakes to correct a prisoner, someone who has beensentenced, one tries to correct the person according to the risk ofrelapse, of recidivism, that is to say according to what will verysoon be called dangerousness – that is to say, again, a mechanismof security.

Foucault, Michel and Graham Burchell (Translator). Security,Territory, Population. 1977-78.Sovereignty is exercised within the borders of a territory,discipline is exercised on the bodies of individuals, and securityis exercised over a whole population.

Foucault, Michel and Graham Burchell (Translator). Security,Territory, Population. 1977-78.scarcity is a state of food shortage that has the property ofengendering a process that renews it and, in the absence of anothermechanism halting it, tends to extend it and make it more acute. Itis a state of scarcity, in fact, that raises prices.

Foucault, Michel and Graham Burchell (Translator). Security,Territory, Population. 1977-78....man’s evil nature will have an influence on scarcity byfiguring as one of its sources, inasmuch as men’s greed – theirneed to earn, their desire to earn even more, their egoism – causesthe phenomena of hoarding, monopolization, and withholdingmerchandise, which intensify the phenomena of scarcity.

Foucault, Michel and Graham Burchell (Translator). Security,Territory, Population. 1977-78....we can say that today's writing has freed itself from thetheme of expression. Referring only to itself; but without beingrestricted to the confines of its interiority, writing isidentified with its own unfolded exteriority.

Foucault, Michel and Josué V. Harari (Translator). What Is anAuthor? 1969.Writing unfolds like a game [jeu] that invariably goes beyondits own rules and transgresses its limits. In writing, the point isnot to manifest or exalt the act of writing, nor is it to pin asubject within language; it is, rather, a question of creating aspace into which the writing subject constantlydisappears.

Foucault, Michel and Josué V. Harari (Translator). What Is anAuthor? 1969.Our culture has metamorphosed this idea of narrative, orwriting, as something designed to ward off death. Writing hasbecome linked to sacrifice, even to the sacrifice of life: it isnow a voluntary effacement that does not need to be represented inbooks, since it is brought about in the writer's veryexistence.

Foucault, Michel and Josué V. Harari (Translator). What Is anAuthor? 1969.Using all the contrivances that he sets up between himself andwhat he writes, the writing subject cancels out the signs of hisparticular individuality. As a result, the mark of the writer isreduced to nothing more than the singularity of his absence; hemust assume the role of the dead man in the game ofwriting.

Foucault, Michel and Josué V. Harari (Translator). What Is anAuthor? 1969.It is a very familiar thesis that the task of criticism is notto bring out the work's relationships with the author, nor toreconstruct through the text a thought or experience, but rather toanalyze the work through its structure, its architecture, itsintrinsic form, and the play of its internalrelationships.

Foucault, Michel and Josué V. Harari (Translator). What Is anAuthor? 1969.The notion of writing, as currently employed, is concerned withneither the act of writing nor the indication – be it symptom orsign – of a meaning that someone might have wanted to express. Wetry, with great effort, to imagine the general condition of eachtext, the condition of both the space in which it is dispersed andthe time in which it unfolds. In current usage, however

Foucault, Michel and Josué V. Harari (Translator). What Is anAuthor? 1969.To admit that writing is, because of the very history that itmade possible, subject to the test of oblivion and repression,seems to represent, in transcendental terms, the religiousprinciple of the hidden meaning (which requires interpretation) andthe critical principle of implicit signification, silentdeterminations, and obscured contents (which give rise tocommentary).

Foucault, Michel and Josué V. Harari (Translator). What Is anAuthor? 1969.The proper name and the author's name are situated between thetwo poles of description and designation: they must have a certainlink with what they name, but one that is neither entirely in themode of designation nor in that of description; it must be aspecific link.

Foucault, Michel and Josué V. Harari (Translator). What Is anAuthor? 1969.These differences may result from the fact that an author's nameis not simply an element in a discourse (capable of being eithersubject or object, of being replaced by a pronoun, and the like);it performs a certain role with regard to narrative discourse,assuring a classificatory function.

Foucault, Michel and Josué V. Harari (Translator). What Is anAuthor? 1969.The author's name manifests the appearance of a certaindiscursive set and indicates the status of this discourse within asociety and a culture. It has no legal status, nor is it located inthe fiction of the work; rather, it is located in the break thatfounds a certain discursive construct and its very particular modeof being.

Foucault, Michel and Josué V. Harari (Translator). What Is anAuthor? 1969.The dawn of madness on the horizon of the Renaissance is firstperceptible in the decay of Gothic symbolism; as if that world,whose network of spiritual meanings was so close-knit, had begun tounravel, showing faces whose meaning was no longer clear except inthe forms of madness.

Foucault, Michel and Richard Howard (Translator). Madness andCivilization. 1964.A fundamental conversion of the world of images: the constraintof a multiplied meaning liberates that world from the control ofform. So many diverse meanings are established beneath the surfaceof the image that it presents only an enigmatic face.

Foucault, Michel and Richard Howard (Translator). Madness andCivilization. 1964.When man deploys the arbitrary nature of his madness, heconfronts the dark necessity of the world; the animal that hauntshis nightmares and his nights of privation is his own nature, whichwill lay bare hell's pitiless truth; the vain images of blindidiocy—such are the world's Magna Scientia; and already, in thisdisorder, in this mad universe, is prefigured what will be thecruelty of the finale.

Foucault, Michel and Richard Howard (Translator). Madness andCivilization. 1964.Then the last type of madness: that of desperate passion. Lovedisappointed in its excess, and especially love deceived by thefatality of death, has no other recourse but madness. As long asthere was an object, mad love was more love than madness; left toitself, it pursues itself in the void of delirium.

Foucault, Michel and Richard Howard (Translator). Madness andCivilization. 1964.Tamed, madness preserves all the appearances of its reign. Itnow takes part in the measures of reason and in the labor of truth.It plays on the surface of things and in the glitter of daylight,over all the workings of appearances, over the ambiguity of realityand illusion, over all that indeterminate web, ever rewoven andbroken, which both unites and separates truth andappearance.

Foucault, Michel and Richard Howard (Translator). Madness andCivilization. 1964.Confinement, that massive phenomenon, the signs of which arefound all across eighteenth-century Europe, is a "police" matter.Police, in the precise sense that the classical epoch gave toit—that is, the totality of measures which make work possible andnecessary for all those who could not live without it...

Foucault, Michel and Richard Howard (Translator). Madness andCivilization. 1964.We have now got in the habit of perceiving in madness a fallinto a determinism where all forms of liberty are graduallysuppressed; madness shows us nothing more than the naturalconstants of a determinism, with the sequences of its causes, andthe discursive movement of its forms; for madness threatens modernman only with that return to the bleak world of beasts and things,to their fettered freedom.

Foucault, Michel and Richard Howard (Translator). Madness andCivilization. 1964.Before Descartes, and long after his influence as philosopherand physiologist had diminished, passion continued to be themeeting ground of body and soul; the point where the latter'sactivity makes contact with the former's passivity, each being alimit imposed upon the other and the locus of theircommunication.

Foucault, Michel and Richard Howard (Translator). Madness andCivilization. 1964.If the passions are possible only in a being which has a body,and a body not entirely subject to the light of its mind and to theimmediate transparence of its will, this is true insofar as, inourselves and without ourselves, and generally in spite ofourselves, the mind's movements obey a mechanical structure whichis that of the movement of spirits.

Foucault, Michel and Richard Howard (Translator). Madness andCivilization. 1964.Madness, then, was not merely one of the possibilities affordedby the union of soul and body; it was not just one of theconsequences of passion. Instituted by the unity of soul and body,madness turned against that unity and once again put it inquestion. Madness, made possible by passion, threatened by amovement proper to itself what had made passion itselfpossible.

Foucault, Michel and Richard Howard (Translator). Madness andCivilization. 1964.For us, the human body defines, by natural right, the space oforigin and of distribution of disease: a space whose lines,volumes, surfaces, and routes are laid down, in accordance with anow familiar geometry, by the anatomical atlas.

Foucault, Michel and A. M. Sheridan (Translator). The Birth ofthe Clinic. 1963.The exact superposition of the ‘body’ of the disease and thebody of the sick man is no more than a historical, temporary datum.Their encounter is self-evident only for us, or, rather, we areonly just beginning to detach ourselves from it.

Foucault, Michel and A. M. Sheridan (Translator). The Birth ofthe Clinic. 1963.Knowledge is historical that circumscribes pleurisy by its fourphenomena: fever, difficulty in breathing, coughing, and pains inthe side. Knowledge would be philosophical that called intoquestion the origin, the principle, the causes of the disease:cold, serous discharge, inflammation of the pleura. The distinctionbetween the historical and the philosophical is not the distinctionbetween cause and effect...

Foucault, Michel and A. M. Sheridan (Translator). The Birth ofthe Clinic. 1963.Disease is perceived fundamentally in a space of projectionwithout depth, of coincidence without development. There is onlyone plane and one moment. The form in which truth is originallyshown is the surface in which relief is both manifested andabolished—the portrait...

Foucault, Michel and A. M. Sheridan (Translator). The Birth ofthe Clinic. 1963.

It is a space in which analogies define essences. The picturesresemble things, but they also resemble one another. The distancethat separates one disease from another can be measured only by thedegree of their resemblance, without reference to thelogico-temporal divergence of genealogy.

Foucault, Michel and A. M. Sheridan (Translator). The Birth ofthe Clinic. 1963.Classificatory thought gives itself an essential space, which itproceeds to efface at each moment. Disease exists only in thatspace, since that space constitutes it as nature; and yet it alwaysappears rather out of phase in relation to that space, because itis manifested in a real patient, beneath the observing eye of aforearmed doctor

Foucault, Michel and A. M. Sheridan (Translator). The Birth ofthe Clinic. 1963.There is no process of evolution in which duration introducesnew events of itself and at its own insistence; time is integratedas a nosological constant, not as an organic variable. The time ofthe body does not affect, and still less determines, the time ofthe disease.

Foucault, Michel and A. M. Sheridan (Translator). The Birth ofthe Clinic. 1963.Doctor and patient are caught up in an ever-greater proximity,bound together, the doctor by an ever-more attentive, moreinsistent, more penetrating gaze, the patient by all the silent,irreplaceable qualities that, in him, betray—that is, reveal andconceal—the clearly ordered forms of the disease.

Foucault, Michel and A. M. Sheridan (Translator). The Birth ofthe Clinic. 1963.In the medicine of species, disease has, as a birthright, formsand seasons that are alien to the space of societies. There is a‘savage’ nature of disease that is both its true nature and itsmost obedient course: alone, free of intervention, without medicalartifice, it reveals the ordered, almost vegetal nervure of itsessence.

Foucault, Michel and A. M. Sheridan (Translator). The Birth ofthe Clinic. 1963.Like civilization, the hospital is an artificial locus in whichthe transplanted disease runs the risk of losing its essentialidentity.

Foucault, Michel and A. M. Sheridan (Translator). The Birth ofthe Clinic. 1963.

http://www.michel-foucault.com/quote/

http://www.michel-foucault.com/quote/2000q.html

http://www.michel-foucault.com/quote/2012q.html

The idea of accumulating everything, of establishing a sort ofgeneral archive, the will to enclose in one place all times, allepochs, all forms, all tastes, the idea of constituting a place ofall times that is itself outside of time and inaccessible to itsravages, the project of organizing in this way a sort of perpetualand indefinite accumulation of time in an immobile place, thiswhole idea belongs to our modernity.

Michel Foucault [1967] "Of Other Spaces," Diacritics 16(Spring 1986), 22-27.

December 2000

'In civilizations without ships, dreams dry up, espionnage takesthe place of adventure and the police take the place of corsairs.'(trans. mod.)

Michel Foucault. (1998) [1984] 'Different spaces'. In J. Faubion(ed.). Tr. Robert Hurley and others. Aesthetics, method andepistemology. The Essential Works of Michel Foucault 1954-1984.Volume Two Harmondsworth, Middlesex: Allen Lane, Penguin, p.181.

November 2000

'All human behavior is scheduled and programmed throughrationality. There is a logic of institutions and in behavior andin political relations. In even the most violent ones there is arationality. What is most dangerous in violence is its rationality.Of course violence itself is terrible. But the deepest root ofviolence and its permanence come out of the form of the rationalitywe use. The idea had been that if we live in the world of reason,we can get rid of violence. This is quite wrong. Between violenceand rationality there is no incompatibility.'

Michel Foucault. (1996) [1980]. 'Truth is in the future'. InSylvère Lotringer (ed.) Foucault Live (Interviews,1961-1984). Tr. Lysa Hochroth and John Johnston. 2nd edition.New York: Semiotext(e), p.299.

October 2000

'What appears to me to be indispensable is respect for thereader... I dream of books which would be clear enough about theway they go about things for others to use them freely, but withouttrying either to blur or hide the original sources. Freedom of useand technical transparency are linked.'

Michel Foucault. (1994) [1983]. 'A propos des faiseursd'histoire'. In Dits et Ecrits vol IV. Paris: Gallimard, p.414. (This passage trans. Clare O'Farrell)

September 2000

'My position is that it is not up to us [intellectuals] topropose. As soon as one "proposes" - one proposes a vocabulary, anideology, which can only have effects of domination. What we haveto present are instruments and tools that people might find useful.By forming groups specifically to make these analyses, to wagethese struggles, by using these insturments or others: this is how,in the end, possibilities open up.

But if the intellectual starts playing once again the role that hehas played for a hundred and fifty years - that of prophet inrelation to what "must be", to what "must take place" - theseeffects of domination will return and we shall have otherideologies, functioning in the same way.'

Michel Foucault. (1988). 'Confinement, psychiatry, prison'. InL. Kritzman, (ed.), Politics, Philosophy, Culture: Interviewsand Other Writings, 1977-1984. New York: Routledge, p.197

August 2000

'... from the moment that people were no longer quite sure ofhaving a soul or that the body would return to life, more attentionto mortal remains became necessary; these became the only trace ofour existence in the midst of the world and in the midst ofwords.

In any case, it was in the nineteenth century that each personbegan to have the right to his own little box for his own personaldecomposition ... (trans. mod)

Michel Foucault. (1998) [1984]. 'Different spaces'. In J.Faubion (ed.). Tr. Robert Hurley and others. Aesthetics, methodand epistemology. The Essential Works of Michel Foucault 1954-1984.Volume Two Harmondsworth, Middlesex: Allen Lane, Penguin, p.181.

July 2000

'[Raymond Roussel] said that after his first book he expectedthat the next morning there would be a kind of aura around hisperson and that everyone in the street would be able to see that hehad written a book. This is the obscure desire harboured byeveryone who writes. It is true that the first text one writes isneither written for others, nor because one is what one is: onewrites to become other than what one is. One tries to modify one'sway of being through the act of writing.' (trans. mod.)

Michel Foucault (1987) 'An interview with Michel Foucault byCharles Ruas'. In Death and the Labyrinth: The World of RaymondRoussel. Tr. C. Ruas. London: The Athlone Press, p.182.

June 2000

'It is hard to see what kind of objectivity is achieved by thestatistical analysis of a questionnaire examining the lies ofschool age children and their playmates. At the end of the day, theresults are reassuring, we learn that children lie mostly to avoidpunishment, then to boast of their exploits etc. We can be sure byvirtue of these very findings, that the method was quite objective.So what? There are those obsessive peeping toms who, in order tolook through a plate glass door, peer through the keyhole'.

Michel Foucault. (1994) [1957]. 'La recherche scientifique et lapsychologie'. In Dits et Ecrits vol I. Paris: Gallimard, pp.137-58. (This passage trans. Clare O'Farrell).

May 2000

'I don't write a book so that it will be the final word; I writea book so that other books are possible, not necessarily written byme'.

Michel Foucault (1994) [1971] 'Entretien avec Michel Foucault'.In Dits et Ecrits vol II. Paris: Gallimard, pp. 157-74.(This passage trans. Clare O'Farrell).

April 2000

'Personally I've never met any intellectuals. I've met peoplewho write novels, others who treat the sick; people who work ineconomics and others who compose electronic music. I've met peoplewho teach, people who paint, and people of whom I have never reallyunderstood what they do. But intellectuals? Never.'

Michel Foucault. (1997). 'The Masked Philosopher'. In J. Faubion(ed.). Tr. Robert Hurley and others. Ethics: Subjectivity andTruth. The Essential Works of Michel Foucault 1954-1984. VolumeOne. Harmondsworth, Middlesex: Penguin, Allen Lane, p. 322.

March 2000

'My role - and that is too emphatic a word - is to show peoplethat they are much freer than they feel, that people accept astruth, as evidence, some themes which have been built up at acertain moment during history, and that this so-called evidence canbe criticized and destroyed.'

Michel Foucault. (1988). 'Truth, power, self: An interview withMichel Foucault October 25 1982'. In Luther H. Martin and PatrickHutton (eds.), Technologies of the Self: A Seminar with MichelFoucault. Massachusetts: University of Massachusetts Press,p.10.

February 2000

'What is serious, is that, as you continue to write you are nolonger read at all and readers going from one distortion toanother, reading books on the shoulders of others end up with anabsolutely grotesque image of your book' (trans. mod.)

Michel Foucault. (1996) [1984]. 'An aesthetics of existence'. InSylvère Lotringer (ed.) Foucault Live (Interviews,1961-1984). Tr. Lysa Hochroth and John Johnston. 2nd edition.New York: Semiotext(e),

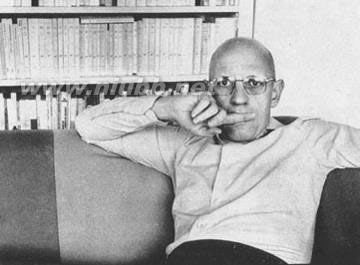

http://baike.soso.com/v2034862.htm?pid=baike.box米歇尔·福柯(MichelFoucault,1926年10月15日-1984年6月25日),法国哲学家和“思想系统的历史学家”。他对文学评论及其理论、哲学(尤其在法语国家中)、批评理论、历史学、科学史(尤其医学史)、批评教育学和知识社会学有很大的影响。他被认为是一个后现代主义者和后结构主义者,但也有人认为他的早期作品,尤其是《词与物》还是结构主义的。他本人对这个分类并不欣赏,他认为自己是继承了现代主义的传统。他认为后现代主义这个词本身就非常的含糊。

米歇尔·福柯(Michel Foucault)1926年10月15日出生于法国维艾纳省省会普瓦捷,这是法国西南部的一个宁静小城。他父亲是该城一位受人尊敬的外科医生,母亲也是外科医生的女儿。在福柯的访谈中,他说,“我小时候生活在法国外省的小资产阶级环境中,我们不得不同家里的客人进行各种谈话,这令我感觉苦不堪言。我常常纳闷,人为什么非得说话不可呢?沉默也许是同别人交往时更有趣的手段。”

(Michel Foucault,1926年10月15日-1984年6月25日),

出生: 1926年10月15日 法国普瓦捷

逝世: 1984年6月25日 法国巴黎

学派/流派: 欧陆哲学、结构主义、後结构主义

主要领域: 观念史、知识论、伦理学、政治哲学

米歇尔·傅柯,法国哲学家和「思想系统的历史学家」。他对文学评论及其理论、哲学(尤其在法语国家中)、批评理论、历史学、科学史(尤其医学史)、批评教育学和知识社会学有很大的影响。他被认为是一个後现代主义者和後结构主义者,但也有人认为他的早期作品,尤其是《词与物》还是结构主义的。他本人对这个分类并不欣赏,他认为自己是继承了现代主义的传统。他认为後现代主义这个词本身就非常的含糊。有人就他的结构主义或後结构主义的倾向质疑他的政治活动。在这一点上他的处境与诺姆·乔姆斯基、乔治·莱考夫和简·雅各布相同。

福柯在普瓦捷完成了小学和中学教育,1945年,他离开家乡前往巴黎参加法国高等师范学校入学考试,并于1946年顺利进入高师学习哲学。1951年通过大中学教师资格会考后,他在梯也尔基金会资助下做了1年研究工作,1952年受聘为里尔大学助教。

早在高师期间,福柯即表现出对心理学和精神病学的极大兴趣,恰好他父母的一位世交雅克琳娜·维尔道(JacquelineVerdeaus)就是心理学家,而雅克琳娜的丈夫乔治·维尔道则是法国精神分析学大师雅克·拉康的学生。因此,在维尔道夫妇的影响下,福柯对心理学和精神分析学进行了系统深入的学习,并与雅克琳娜一道翻译了瑞士精神病学家宾斯万格尔(LudwigBinswanger)的著作《梦与存在》。书成之后,福柯应雅克琳娜之请为法文本做序,并在1953年复活节之前草就一篇长度超过正文的序言。在这篇长文中,他日后光彩夺目的写作风格已经初露端倪。1954年,这本罕见的序言长过正文的译作由德克雷·德·布鲁沃出版社出版,收入《人类学著作和研究》丛书。同年,福柯发表了自己的第一部专著《精神病与人格》,收入《哲学入门》丛书,由法国大学出版社出版。福柯后来对这部著作加以否定,认为它不成熟,因此,1962年再版时这本书几乎面目全非。

1955年8月,在著名神话学家乔治·杜梅泽尔(Georges Dumezil)的大力推荐下,福柯被瑞典乌普萨拉大学聘为法语教师。在瑞典期间,福柯还兼任法国外交部设立的“法国之家”主任,因此,教学之外,他花了大量时间用于组织各种文化交流活动。在瑞典的3年时间里,福柯开始动手撰写博士论文。得益于乌普萨拉大学图书馆收藏的一大批16世纪以来的医学史档案、书信和各种善本图书,也得益于杜梅泽尔的不断督促和帮助,当福柯离开瑞典时《疯癫与非理智——古典时期的疯癫史》已经基本完成。

1958年,由于感到教学和工作负担过重对,福柯提出辞职,并于6月间回到巴黎。两个月后,还是在杜梅泽尔的帮助下,同时也因为福柯在瑞典期间表现的出色组织能力,他被法国外交部任命为设在华沙大学内的法国文化中心主任。这年10月,福柯到达波兰,不过他并没有在那儿待太久,原因倒也富于戏剧性:他中了波兰情报机关的美男记。福柯从很早时候起就是同性恋,对此他倒不加掩饰,就个人生活而言,这位老兄显然够得上“风流”的美名。然而50年代正是东西方冷战正酣之时,两方都在挖空心思的相互刺探。恰恰在1959年,法国驻波兰大使馆文化参赞告假,大使本已有心提拔福柯,便一面让他代行参赞职务,一面行文报请正式任命。所以波兰情报机构乘虚而入,风流成性的年轻哲学家合当中计。

离开波兰后,福柯继续他的海外之旅,这一次是目的地是汉堡,仍然是法国文化中心主任。1960年2月,福柯在德国最终完成了他的博士论文。这是一本在厚度和深度上都同样令人匝舌的大书:全书包括附录和参考书目长达943页,考察了自17世纪以来疯癫和精神病观念的流变,详尽梳理了在造型艺术、文学和哲学中体现的疯癫形象形成、转变的过程及其对现代人的意义。按照惯例,申请国家博士学位的应该提交一篇主论文和一篇副论文,福柯因此决定翻译康德的《实用人类学》并以一篇导言作为副论文,虽然这一导言从来没有出版,但福柯研究者们发现,他后来成熟并反映于《词与物》、《知识考古学》中的一些重要概念和思想,在这篇论文中其实已经形成。

应福柯之请,他以前在亨利四世中学的哲学老师,时任巴黎高师校长的让·伊波利特(JeanHyppolite)欣然同意作副论文的“研究导师”,并推荐著名科学史家、时为巴黎大学哲学系主任的乔治·冈奎莱姆(GeorgesConguilhem)担任他的主论文导师。后者对《疯癫史》赞誉有加,并为他写了如下评语“人们会看到这项研究的价值所在,鉴于福柯先生一直关注自文艺复兴时期至今精神病在造型艺术、文学和哲学中反映出来的向现代人提供的多种用途;鉴于他时而理顺、时而又搞乱纷杂的阿莉阿德尼线团,他的论文融分析和综合于一炉,它的严谨,虽然读起来不那么轻松,但却不失睿智之作……因此,我深信福柯先生的研究的重要性是毋庸置疑的。”[1]1961年5月20日,福柯顺利通过答辩,获得文学博士学位。这篇论文也被评为当年哲学学科的最优秀论文,并颁发给作者一枚铜牌。

词与物书影

福柯画像

还在福柯通过博士论文答辩以前,克莱蒙-费朗大学哲学系新任系主任维也曼在读完《疯癫史》手稿后,即致函尚远在汉堡的作者,希望延聘他为教授。福柯欣然接受,并于1960年10月就任代理教授,1962年5月1日,克莱蒙-费朗大学正式升任福柯为哲学系正教授。在整个60年代,福柯的知名度随着他著作和评论文章的发表而急剧上升:1963年《雷蒙·鲁塞尔》和《临床医学的诞生》,1964年《尼采、弗洛伊德、马克思》以及1966年引起极大反响的《词与物》。

这部著作力图构建一种“人文科学考古学”,它“旨在测定在西方文化中,人的探索从何时开始,作为知识对象的人何时出现。” [1]福柯使用“知识型”这一新术语指称特定时期知识产生、运动以及表达的深层框架。通过对文艺复兴以来知识型转变流动的考察,福柯指出,在各个时期的知识型之间存在深层断裂。此外,由于语言学具有解构流淌于所有人文学科中语言的特殊功能,因此在人文科学研究中,语言学都处于一个十分特殊的位置:透过对语言的研究,知识型从深藏之处显现出来。这本书“妙语连珠,深奥晦涩,充满智慧”[1],然而就是这样一本十足的学术论著,甫经出版即成为供不应求的畅销书:第一版由法国最著名的伽利玛出版社于1966年10月出版,印了3500册,年底即告售磬,次年6月再版5000册,7月:3000,9月:3500,11月:3500;67年3月:4000,11月:5000……,据说到80年代为止,《词与物》仅在法国就印刷了逾10万册。对这本书的评价也同样戏剧,评论意见几乎截然二分,不是大加称颂,就是愤然声讨,两造的领军人物也个个了得:被誉为“知识分子良心”的大哲学家萨特声称这本书“要建构一种新的意识形态,即资产阶级所能修筑的抵御马克思主义的最后一道堤坝”,法国共产党的机关杂志也连续发表批驳文章;不过更有意思的是,这一次,天主教派的知识分子们同似乎该不共戴天的共产党人们站到了同一条战线里:虽然进攻的方式有所不同,但在反对这一点上,两派倒是心有期期。但福柯这一方的阵容也毫不逊色:冈奎莱姆拍案而起,他于1967年发表长文痛斥“萨特一伙”对《词与物》的指责,并指出争论的焦点其实并不在于意识形态,而在于福柯所开创的是一条崭新的思想系谱之路,这恰恰又是固守“人本主义”或“人道主义”的萨特等所不愿意看到并乐意加以铲除的。

不管怎样,《词与物》为福柯带来了巨大声望。不久,福柯又一次离开了法国,前往突尼斯大学就任哲学教授。福柯在突尼斯度过了1968年5月运动的风潮。这是一个“革命”的口号和行动时期遍及欧洲乃至世界的时期,突尼斯爆发了一系列学生运动,福柯投身于其中,发挥了相当的影响。此后,他的身影和名字也一再出现于法国国内一次又一次的游行、抗议和请愿书中。

68年5月事件促使法国教育行政当局反思旧大学制度的缺陷,并开始策划改革之法。作为实验,1968年10月间,新任教育部长艾德加·富尔决定在巴黎市郊的万森森林兴建一座新大学,它将拥有充分的自由来实验各种有关大学教育体制改革的新想法。福柯被任命为新学校的哲学系主任。但是,万森很快就陷入无休止的学生罢课、与警察的临街对峙乃至火爆冲突中,福柯的哲学系也在极左派的吵嚷声中成为动乱根源。在万森两年,是使福柯感到筋疲力尽的两年。

1972年12月2日,对福柯来讲是一个具有纪念意义的日子,这一天,他走上了法兰西学院高高的讲坛,正式就任法兰西学院思想体系史教授。进入法兰西学院意味着达学术地位的颠峰:这是法国大学机构的“圣殿中的圣殿”。

70年代的福柯积极致力于各种社会运动,他运用自己的声望支持旨在改善犯人人权状况的运动,并亲自发起“监狱情报组”以收集整理监狱制度日常运做的详细过程;他在维护移民和难民权益的请愿书上签名;与萨特一起出席声援监狱暴动犯人的抗议游行;冒着危险前往西班牙抗议独裁者佛朗哥对政治犯的死刑判决……。所有这一切都促使他深入思考权力的深层结构及由此而来的监禁、惩戒过程的运作问题。这些思考构成了他70年代最重要一本著作的全部主题——《规训与惩罚》。

福柯的最后一部著作《性史》的第一卷《求知意志》在1976年12月出版,这部作品的目的是要探究性观念在历史中的变迁和发展。福柯对这部性的观念史寄予厚望,并以务求完美的态度加以雕琢,大纲和草稿改了一遍又一遍,以至最终文本与最初计划相差甚大。这又是一部巨著,按照福柯最后的安排,全书分为四卷,分别为《求知遗志》、《快感的享用》、《自我的呵护》、《肉欲的告赎》。可惜的是,作者永远也看不到它出齐了,1984年6月25日,福柯因艾滋病在巴黎萨勒贝蒂尔医院病逝,终年58岁。

福柯的死使法国上下震惊。共和国总理和教育部长称“福柯之死夺走了当代最伟大的哲学家……凡是想理解20世纪后期现代性的人,都需要考虑福柯。”《世界报》、《解放报》、《晨报》、《新观察家》等报刊相继刊发大量纪念文章。思想界的重要人物也纷纷发表纪念文字:年鉴学派大师费尔南·布罗代尔称“法国失去了一位当代最光彩夺目的思想家,一位最慷慨大度的知识分子”;乔治·杜梅泽尔的纪念文章感人肺腑,老人老泪纵横的谈到以前常说的话“我去世时,米歇尔会给我写讣告。”然而,事实无情,颠倒的预言更加使人悲从心来:“米歇尔·福柯弃我而去,使我感到失去很多东西,不仅失去了生活的色彩也失去了生活的内容。”

米歇尔·福柯(1926-1984)

6月29日上午,福柯的师长和亲友在医院举行了遗体告别仪式,仪式上,由福柯的学生,哲学家吉尔·德勒兹宣读悼文,这段话选自福柯最后的著作《快感的享用》,恰足以概括福柯终身追求和奋斗的历程,我也就用这段话来结束这篇为纪念福柯逝世18周年而做的短文吧:

“至于说是什么激发着我,这个问题很简单。我希望在某些人看来这一简单答案本身就足够了。这个答案就是好奇心,这是指任何情况下都值得我们带一点固执地听从其驱使得好奇心:它不是那种竭力吸收供人认识的东西的好奇心,而是那种能使我们超越自我的好奇心。说穿了,对知识的热情,如果仅仅导致某种程度的学识的增长,而不是以这样或那样的方式尽可能使求知者偏离自我的话,那这种热情还有什么价值可言?在人生中:如果人们进一步观察和思考,有些时候就绝对需要提出这样的问题:了解人能否采取与自己原有的思维方式不同的方式思考,能否采取与自己原有的观察方式不同的方式感知。……今天的哲学——我是指哲学活动——如果不是思想对自己的批判工作,那又是什么呢?如果它不是致力于认识如何及在多大程度上能够以不同的方式思维,而是证明已经知道的东西,那么它有什么意义呢?”

192610月15日生于法国中西部文化教育古城普瓦捷。父亲保罗·米歇尔·福柯和祖父保罗·安德烈·福柯都是医生。母亲安妮·玛丽·马拉贝也是医学世家出身,她的父亲是外科医生兼普瓦捷医学院医学教授。

1934 7月26日奥地利首相多弗斯遭法西斯分子枪杀,年幼的福柯“生平中第一次感觉到死亡的震撼”。

1936 为训练福柯兄妹三人在日常生活中使用英语,家里请来一位英籍修女陪伴他们。

1937 福柯向父亲宣告他长大后将选择当历史学教授,不愿意继承家业当医生,首次表现出他的叛逆性格。

1940 进入由天主教修士创建的斯旦尼斯拉夫书院。

1942由于学校哲学教师被德军关押在集中营,母亲特地请一位哲学系学生路易·杰拉特为福柯补习哲学,同时还向学校推荐一位天主教修士担任哲学教师。

1943 福柯获高中毕业文凭,并升入普瓦捷的路易四世大学预备班,为升入巴黎高等师范学院作准备。

1945报考巴黎高等教师学院第一次失败后,进入巴黎亨利四世大学预备班,遇见名哲学家依波利特,从此师从依波利特,在哲学及人文社会科学方面奠定了坚实的基础。

1946福柯成功考入巴黎高等师范学院,师从阿尔杜塞、依波利特等名师。但他的身体健康状况,特别是在性生活方面,遇到了麻烦,而且因表现出同性恋的倾向而苦恼。

1947 原本在里昂大学任教的梅格宠蒂,开始在巴黎高等师范学院教授心理学,使福柯能够以新的观点准备他的心理学论文。

1948 福柯在巴黎大学取得哲学硕士学位。福柯产生自杀念头。

1949海洛宠蒂升任巴黎大学心理学教授,并开讲“人的科学与现象学”的课程,给予福柯深刻的印象。福柯在依波利特指导下开始准备他的论黑格尔的博士论文。

1950 福柯加入法国共产党,同时再次出现自杀念头,并到医院接受戒毒治疗。

1951获大学哲学教师资格文凭,退出法国共产党,并在冈格的指导下,准备哲学国家博士文凭。从此,福柯还担任巴黎高等师范学院心理学讲师,同时准备考取心理学和精神分析学医生资格。

1953 福柯能加贝克特《等待弋多》新书发表会,促使他的思想发生根本性转折,从此对布朗肖、巴塔耶和尼采深感兴趣。福柯参加拉康的研讨会,并研究德国精神病治疗学、神学和人类学,特别集中研究和着手翻译宾斯万格的著作,对其中的《疯狂只是生平现象》深感兴趣。当年夏天,福柯亲自前往瑞士精神病治疗学家罗兰·库恩在医院中举办的精神病人嘉年华晚会。同年获心理学学院的实验心理学文凭,取代阿尔杜塞而在巴黎高等师范学院担任哲学讲师。

1954发表《精神病与人格》。在该书的结论中,福柯说:“真正的心理学,如同其他关于人的科学一样,应以帮助人从异化状态中解除出来作为其宗旨。”在巴黎高等师范学院讲授《现象学和心理学》。

1957 7月返回巴黎度假,在克尔狄出版社发现鲁塞尔的文学著作,从此很重视鲁塞尔作品中的语言风格。年底,在乌普萨拉会见前往瑞典接受诺贝尔文学奖的加缪。依波利特审阅福柯的《精神病的历史》草稿,并建议作为博士论文交给冈格彦审核。

1958福柯离开瑞典前往华沙,担任华沙大学法国文化中心主任,密切注视当时发生在波兰的政治事件。10月,前往德国汉堡担任当地法国文化中心主任。

1960起草他的第二篇博士论文《论康德人类学的形成及其结构》,并翻译康德的《从实用观点看的人类学》。4月,福柯的导师冈格彦向克莱费朗大学哲学系主任居尔·维尔敏教授推荐福柯担任高级讲师。《精神病的历史》被迦里马出版社拒绝。经著名历史学家阿里耶斯的同意,《精神病的历史》作为在阿里耶斯主编的《文明与心态》丛书中的一本,由伯朗出版社在1961年5月正式出版。10月,认识刚刚考入圣格鲁师范学院的一位哲学系学生丹尼尔·德斐特,他从此成为福柯的终身同性恋伴侣。

19615月在巴黎大学答辩他的国家博士论文《精神病与非理性:古典时期精神病的历史》与《康德人类学》;前一篇由冈格彦和丹尼尔·拉加斯指导,后一篇由依波利特指导。《精神病与百理性:古典时期精神病的历史》立即受到历史学家曼德鲁和布罗代洋以及作家布朗肖的高度肯定。福柯被任命为巴黎高等师范学院入学考试审查委员会委员。在广播电台发表《精神病的历史与文学》的系列演讲。年底,《诊疗所的诞生》完稿,并起草《雷蒙德·鲁塞尔》。

1962修改《精神病与人格》,从此该书改名为《精神病与心理学》。结识吉尔·德勒兹,从此成为他的至交。阅读法国著名医学家和解剖学家比沙和作家萨德的著作时,对“死亡”概念进行精避的知识论分析。他认为,“死亡”并不是如同传统医学理论所说的那样是一个“点”,或者,更确切地说,是一个生存的终点,而是一条模糊不清的“线”,人在这条“线”上来来去去不断来回穿越。“死亡”,就是人在来来去去的穿越中,同其自身的来回遭遇。也就是说,所谓“死亡”,就是人在一条不确定的线上的来来去去过程中,不断地与自身遭遇和相交错。福柯说:“萨特与比沙,这两位同时代人是相异的双胞胎。他们俩把死亡和性置于西方人的身体中。这两种经验都缺少自然色彩,表现出逾越的性质,但同时又包含着绝对争议性的权力,以至现代文化以它为基础,幻想建构一种能够显示自然人的知识。”福柯被任命为克莱蒙费朗大学心理学教授,并担任哲学系主任。

19634月出版《诊疗所的诞生:一种医学望诊的考古学》和《雷蒙德·鲁塞尔》。外交部任命福柯为东京法国文化中心主任,但由于福柯舍不得离开丹尼尔·德斐特,放弃了这个职务。重读海德格尔的著作。

1964与新尼采主义者德勒兹、克罗索斯基、吉恩·波费雷特、享利·毕洛、瓦狄默、吉恩·瓦尔、卡尔·勒维兹、科利及蒙狄纳里等人筹划新版《尼采全集》。

1966年初,正当他的《语词与事物》付诸排印时,福柯在致友人的一封信中指出:“哲学是诊断的事业,而考古学是描述思想的方法”由德勒兹一起担任《尼采全集》法文部分的主编。4月,发表《语词与事物:人文科学的考古学》。与德里达和阿尔杜塞频繁来往,并宣布“我们的任务是坚决地超越人文主义”。9月,福柯决定移居突尼斯。法国掀起结构主义浪潮。10月,萨特发表批评福柯及结构主义的文章,指责福柯是“资产阶级的最后堡垒”。

1967 福柯对发生在中国的“文化大革命”深感兴趣。年底访问米兰,结识安伯托·艾柯。

1968 重读贝克特与罗莎·卢森堡的著作。5月,巴黎爆发学生运动和全国罢工,福柯停留在突尼斯,支持当地的学生运动。10月27日,福柯的导师依波利特逝世。年底,任巴黎第八大学教授。

1969福柯积极参与巴黎第八大学的学生运动,支持学生造反。开讲“性与个人”等课程。2月22日,应法国哲学会邀请发表认考古学的演讲,强调他们德里达和罗兰·巴特之间的差异。3月,《知识考古学》发表。11月30日,法兰西学院决定将依波波处特原调的“哲学思想史”讲座改名为“思想体系史”。福柯是该讲座的候选人之一。

1970福柯被纽约大学邀请前往美国,发表论萨德的论文,并在耶鲁大学进行演讲,访问福克纳的故乡。4月,福柯被正式选为法兰西学院终身讲座教授。5月,为新版《巴塔耶全集》写序。福柯的法兰西学院教授身份促使该版《巴塔耶全集》避免了许多政府出版禁令。在该书的发表会上,福柯乘机为居约达的禁书《伊甸,伊甸,伊甸》翻案,使该书得以正式出版。9月,前往日本访问,发表《论马奈》、《精神病与社会》及《返回历史》等学术演讲。11月,访问意大利佛教罗伦萨,再次发表论马奈的论文。12月,在法兰西学院发表就职演说,论述他的知识考古学研究的特征,并宣布即将开讲“知识的意愿”。

1971 2月,为了支持举行绝食抗议的政治犯,福柯决定成立“监狱情报团体”简称GIP,该组织总部就设在福柯的寓所,而他的伴侣丹尼尔·德斐特成为该组织负责人。与此同时,福柯还支持并参与由萨特等人所组织的“人民法庭”,但在斗争策略方面与萨特等人略有不同。以福柯在法兰西学院的就职演说为蓝本。《论述的秩序》正式发表。春,“监狱情报团体”在法国各监狱散发调查表。到加拿大魁北克地区的麦克吉尔大学访问,同当地反政府的独立分子接触,并在监狱中会见受监禁的《美洲白色黑奴》的作都瓦里耶。5月,福柯等人在监狱门口以“煽动者”的罪名被警察逮捕。与“监狱情报团体”所写的《对二十所监狱所做的调查表报告》公开发表。福柯还需要热内一起,支持受迫害的美国黑人领袖乔治·杰克逊。7月,法国监狱容许犯人看报纸及听广播电台的广播,这是由福柯领导的“监狱情报团体”所作的斗争的第一次胜利。9月,福柯多次表示反对死刑。年底,在法兰西学院开讲“惩治理论与制度”。在巴黎“互助之家”举办电影晚会,放映描述监狱状况的影片,福柯同萨特和热内表示对当代监狱制度的抗议。接受电视协会的邀请前往荷兰,同美国语言学家乔姆斯基就人的本性问题进行辩论。“监狱情报团体”发表第二篇监狱调查报告《对一所典型监狱的调查》。

1972福柯同萨特、德勒兹、莫里亚克等,静坐在法国法务部庭院,抗议不合理的监狱制度。福柯再次被捕。释放后第二天,福柯亲自架车同萨特前往造反中的雷诺汽车工厂,支持造反中的工人。德勒兹与加达里合著的《资本主义与精神分裂症》第一卷《反俄狄浦斯》出版,福柯向德勒兹祝贺时说:“应该从弗洛伊德主义的马克思主义中摆脱出来。”德勒兹回答说:“我负责弗洛伊德,你对付马克思,好吗?”法国《拱门》杂志发表福柯与德勒兹的讨论集,两位哲学家都集中地谈论权力问题。4月福柯再次访问美国,分别在纽约、明尼阿波利斯等地,发表《古希腊时期真理的意愿》和《17世纪的礼仪、戏剧及政治》,并访问阿狄卡监狱,表示:“监狱并不仅是真有镇压功能,而且还有监禁权力的生产功能。”10月,受到美国康奈尔大学邀请,发表《文学与罪行》、《惩治的社会》等。年底,在法兰西学院开讲《皮埃尔·里维耶及其作品》。“监狱情报团体”解散。福柯参与筹划创立《解放报》。

1973“监狱情报团体”的第四篇监狱调查报告《监狱中的自杀事件》,在德勒兹的主持下正式出版,福柯在法兰西学院开讲“规训的社会”,这一课程后来改名为“惩治的社会”。在其中,福柯还把“排除的社会”严格地同“封闭的社会”区分开来。5月,前往蒙特利尔、纽约和里约热内卢等地进行学术访问。9月,《我,皮埃尔·里维耶》出版,深受欢迎。10月,出版《这不是一支烟斗》。

1974在法兰西学院开计《精神病治疗学的权力》,并主持有关18世纪医院结构以及自1830年以来精神病治疗学清规戒律学科状况的研讨会。4月,由于《研究》杂志曾经发表《同性恋百科全书》,受到法律追究。福柯为此发表谈话,指出“到底要等到什么时候,同性恋获得发言和进行正常性活动的权利?”7月,对德国导演斯洛德,希尔伯贝格及法斯宾德等人的影片深感兴趣,并接见瑞士导演丹尼尔·施密特,对影片中的性与身体的表现方法等问题发表意见。福柯等人还发表《公开讨论监禁制度》的备忘录档,呼吁政府改善并维护犯人的基本人权。年底,在里约热内卢主持有关“城市化与公共卫生”及“19世纪精神病治疗学中的精神分析系统谱学”的研讨会。

1975在法兰西学院诗有关“精神病治疗学的法医”研讨会,并开讲“导常者”的系列课程。2月,继续研究画家马奈等人的作品,深入研究绘画与摄影的相互关系。《监视与惩罚:监狱的诞生》正式出版。4月,《观察家》杂志发表专刊《法国大学的偶像:拉康、巴特、李欧塔和福柯》,描述福柯在法兰西学院讲课时的那种庄重,严肃及备受尊敬的、几站接近偶像崇拜的神秘气氛。春天,访问加利福尼亚非大学,发表《论述与镇压》和《弗洛伊德以前的儿童性欲研究》,并同德勒兹会晤和展开讨论,引起美国大学生的广泛兴趣。同时,还对当地同性恋、吸毒、禅宗、女性主义等社会小团体的活动深感兴趣,大加赞扬。9月,支持西班牙反佛朗哥独裁政权的政治犯,要求西班牙政府给予无条件释放。

1976年初,“必须保卫社会”在法兰西学院开讲。福柯宣布将结束五年来对权利的镇压模式的研究,并试图将权力关系的动作过程描述成战争模式。福柯说:“已经耗用五年的时间研究规训问题,今后五年将集中研究战争和斗争。……我们只能通过真理的生产来实行权力。”5月,在伯克利和斯坦福进行学术演讲。8月,《知识的意愿》手稿完成。12月《知识的意愿》作为《性史》第一卷正式发表。

1977《知识的意愿》在读者中受到欢迎,特别是受到女性主义者和同性恋者的喝彩。由于《监视与征罚》英文版的出版,福柯受到美国知识界和学术界的广泛注意。年底访问东西柏林,讨论监狱问题,被联帮警察逮捕。

1978在法兰西学院开讲“安全、领土与居民”的课程,重点从原来的权力问题转向统治心态问题。开始起草《性史》第二卷。4月,访部日本,连续发表“性与权力”、“权力的基督教教士模式”、“关于马克思与黑格尔”等演讲。5月,出席法国哲学会,发表“什么是批判”的学术演讲,但福柯表示,他个人倾向于将题目改为“什么是启蒙”。夏天,福柯因车祸脑震荡而入医院。后来,当萨特殊性在1980年逝世时,福柯曾对莫里亚克说:“从那以后,我的生活发生了改变。车祸时,汽车震撼了我,我被势到车盖上面。我利用那一点时间想过,完了,我将死去;这很好。我当时没意见。”9月,匆匆访问伊朗,试图支持当时反抗独裁统治的伊朗民主人士。11月,同萨特等人积极支持越南难民。12月意大利记者特龙巴多里向福柯建议,开展同意意大利马克思主义者的学术讨论。

1979 从年初开始研究古基督教教父哲学文献,主要探讨基督教关于“忏悔”的历史,以便探索基督教采取何种方式对基督教徒个人进行思想控制。在此基础上,确定了《性史》第二卷的基本内容,并将基督教这种特殊的思想控制方式称为“权力的基督教教士运作模式”。课程“生命权力的诞生”开讲。此课程所批判别的主要对象是现代自由主义社会。福柯宣称:“国家没有本质,国家不是一种普通性的概念,本身并非权力的自律源泉。国家无非是无止境的国家化过程。”4月,福柯为法国第一本同性恋杂志《LeGai Pied》创刊号撰写一篇支持自杀的文章。为此,福柯遭到法国各大报刊的批判。10月前往斯坦福大学,为坦纳尔讲座讲授统治心态。

1980在法兰西学院开讲“对活人的统治”。2月,福柯接受《世界报》访问,他要求该报不该发表他的名字,《世界报》为此称之为“戴假面具的哲学家”。3月26日,罗兰·巴特因车祸去世。4月9日,福柯参加萨特的葬礼,同成千成万的群众护送萨特的灵柩前往墓地。8月,阿兰·施里旦发表论福柯的英文著作《真理意志》。9月英国记者在柏克利大学发表《真理情形主体性》,并支持“从古代晚期到基督教诞生时期的性伦理”的研究会。11月,在纽约大学发表《性与孤独》。在达尔姆斯学院发表《主体性与真理》及《基督教与忏悔》。在普林斯顿大学发表《生命权力的诞生》。

1981 年初,在法兰西学院开讲“主体性与真理”,探讨“自身的技术”作为管辖自身的方式究竟如何运作。5月,在鲁汶大学法学院发表《做坏事,说好话:论法律程序中的招认和见证的功能》。福柯认为,资产阶级现代法律中的某些重要程序,是延续和继承基督教“忏悔”的手段,玩弄权术游戏。10月,受马克·波斯特邀请,前往洛杉矶,参加“知识、权力与历史:对于福柯的著作的多学科研究取向”的研讨会。会见法兰克福学派的成员洛文达尔和马丁·杰伊。纽约《时代周刊》发表《法国的权力哲学家》。福柯说:“我更加感兴趣的,并不是权力,而是主体性的历史。”在伯克利,准备建立“福柯—哈贝马斯研讨会”,哈贝马斯希望他的主要论题是“现代性”。

1982春,福柯抗议捷克当局逮捕在布拉格访问中的德里达。5月,前往多伦多参加符号论及结构主义方法研讨会,会见库尔勒、艾柯等人。发表《古代文化中对于自身的关怀》。从此,福柯研究重点转向斯多葛学派哲学。6月,打算辞去法兰西学院的讲座教授职务,以便移居伯克利。7月,患慢性鼻腔炎。8月,巴黎犹太餐厅遭恐怖分子炸弹威协,福柯决定经常前往进餐,以示抗议。10月,在佛蒙特大学发表《自身的技术》

1983在法兰西学院开讲“对自身与他人的管辖”的课程。3月,完成《性史》第二卷的绝大部分草稿,书名为《快感的运用》。哈贝马斯在法兰西学院演讲,与福柯会见。英文版《福柯作品评注》由迈克尔·克拉克主编,正式出版。4月,前往伯克利发表《关于自身的艺术与自身的书写》。10月,再次访问伯克利,连续六次学术演讲,并在布尔德和圣德·克鲁兹做两次学术演讲,至使他极度疲劳,决定不再在法兰西学院授课,并从此回避在公众场合露面。准备翻译伊莱亚斯的《死者的一次性》。12月,卧病不起。

1984年初,接受抗菌素治疗,身体稍有好转。福柯在一封致莫里斯·炳格的信中说:“我得了艾滋病。”2月,身体再度感到疲倦,但坚持恢复在法兰西学院的课程,并修改《性史》第二卷草稿。3月,伯克利大学与福柯合作研究的师生,针对20世纪30年代后西方国家政府统治心态的变迁,寄来一份研究计划。其中提到,自第一次世界大战以来,西方社会在社会生活、经济计划化及政治组织三大方面行了重建。他们为此主张对新产生的政治合理性问题进行深入研究,提出了五项研究计划:(一)美国的福利国家与进步主义;(二)意大利的法西斯与休闲组织;(三)法国的社会救济国家及其在殖民地的城建实验;(四)在苏联的社会主义建设;(五)包豪斯的建筑与魏玛共和国。这时,福柯经常到医院就医。但他并不要求医生给予治疗,唯一关心的问题,就是“我到底还有多少时间”。早在1978年,福柯曾经就死亡问题与法国著名死亡问题研究专家阿里耶斯讨论。他当时说:“为了成为自己同自身的死亡的秘密关系的主人,病人所能忍受的,就是认知与寂静的游戏。”3月10日,福柯在继续修改草稿的同时,接见被警察驱逐的马里和塞内加尔移民,并要求政府当局合理解决他们的问题。5月,《文学杂志》发表福柯专号,庆贺《性史》第二卷和第三卷出版。6月,福柯身体健康状况恶化。6月25日,福柯去世。

福柯的主要工作总是围绕几个共同的组成部分和题目,他最主要的题目是权力(power)和它与知识的关系(知识的社会学),以及这个关系在不同的历史环境中的表现。他将历史分化为一系列“认识”,福柯将这个认识定义为一个文化内一定形式的权力分布。

对福柯来说,权力不只是物质上的或军事上的威力,当然它们是权力的一个元素。对福柯来说,权力不是一种固定不变的,可以掌握的位置,而是一种贯穿整个社会的“能量流”。福柯说,能够表现出来有知识是权力的一种来源,因为这样的话你可以有权威地说出别人是什么样的和他们为什么是这样的。福柯不将权力看做一种形式,而将它看做使用社会机构来表现一种真理而来将自己的目的施加于社会的不同的方式。

比如福柯在研究监狱的历史的时候他不只看看守的物理权力是怎样的,他还研究他们是怎样从社会上得到这个权利的——监狱是怎样设计的,来使囚犯认识到他们到底是谁,来让他们铭记住一定的行动规范。他还研究了“罪犯”的发展,研究了罪犯的定义的变化,由此推导出权力的变换。

对福柯来说,"真理”(其实是在某一历史环境中被当作真理的事物)是运用权力的结果,而人只不过是使用权力的工具。

福柯认为,依靠一个真理系统建立的权力可以通过讨论、知识、历史等来被质疑,通过强调身体,贬低思考,或通过艺术创造也可以对这样的权力挑战。

福柯的书往往写得非常紧凑,充满了历史典故,尤其是小故事,来加强他的理论的论证。福柯的批评者说他往往在引用历史典故时不够小心,他常常错误地引用一个典故或甚至自己创造典故。

爱华网

爱华网