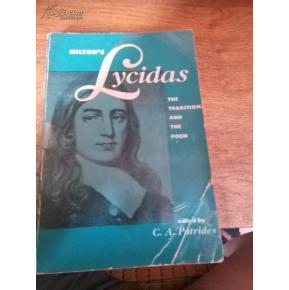

《利西达斯》(Lycidas),也译为黎西达斯,是约翰·弥尔顿的一首诗(1638年)。诗的题目源自维吉尔的《田园诗》中一个牧羊人的名字。《利西达斯》是一首田园挽歌,纪念一年前在爱尔兰海的一次海难不幸去世的爱德华国王,他是弥尔顿在剑桥时的同学。同时弥尔顿这首诗还抨击了腐败的僧侣阶层。

eumendies_利西达斯 -原文

Lycidas

In thismonodythe Author bewails a

learnedFriend, unfortunatly drown'd in his Passage

from Chester on the Irish Seas, 1637. And by

occasion fortels the ruine of our corrupted

Clergy then in their height.

YEt once more, O ye Laurels, and once more

Ye Myrtles brown, with Ivy never-sear,

I com to pluck your Berries harsh and crude,

And with forc'd fingers rude,

Shatter your leaves before the mellowing year. [ 5 ]

Bitter constraint, and sad occasion dear,

Compels me to disturb your season due:

For Lycidasis dead, dead ere his prime,

Young Lycidas, and hath not left his peer:

Who would not sing for Lycidas? he knew [ 10 ]

Himself to sing, and build the lofty rhyme.

He must not flote upon his watrybear

Unwept, andwelterto the parching wind,

Without the meed of sommelodioustear.

Begin then, Sistersof the sacred well, [ 15 ]

That from beneath the seat ofJovedoth spring,

Begin, and somwhat loudly sweep the string.

Hence with denial vain, and coy excuse,

So may som gentle Muse

Withluckywords favour my destin'd Urn, [ 20 ]

And as he passes turn,

And bid fair peace be to my sable shrowd.

For we were nurst upon the self-same hill,

Fed the same flock, by fountain, shade, and rill.

Together both, ere the high Lawns appear'd [ 25 ]

Under theopeningeye-LIDSof the morn,

We drove a field, and both together heard

What time the Gray-fly winds hersultryhorn,

Batt'ningour flocks with the fresh dews of night,

Oft till theStarthat rose, at Ev'ning, bright [ 30 ]

Toward Heav'ns descent had slop'd hiswesteringwheel.

Mean while the Rural ditties were not mute,

Temper'd to th'oatenFlute,

Rough Satyrsdanc'd, and Fauns with clov'n heel,

From the glad sound would not be absent long, [ 35 ]

And old Damœtaslov'd to hear our song.

But O the heavy change, now thou art gon,

Now thou art gon, and never must return!

Thee Shepherd, thee the Woods, and desert Caves,

With wilde Thyme and the gaddingVine o'regrown, [ 40 ]

And all their echoes mourn.

The Willows, and the Hazle Copses green,

Shall now no more be seen,

Fanning their joyous Leaves to thy soft layes.

As killing as the Cankerto the Rose, [ 45 ]

Or Taint-wormto the weanlingHerds that graze,

Or Frost to Flowers, that their gay wardropwear,

When first the White thorn blows;

Such, Lycidas, thy loss to Shepherds ear.

Where were ye Nymphs when the remorseless deep [ 50 ]

Clos'd o're the head of your lov'd Lycidas?

For neither were ye playing on the steep,

Where your old Bards, the famous Druids ly,

Nor on theshaggytop of Monahigh,

Nor yet where Devaspreads her wisard stream: [ 55 ]

Ay me, I fondlydream!

Had ye bin there ― for what could that have don?

What could the Muse her self that Orpheusbore,

The Muse her self, for her inchanting son

Whom Universal nature did lament, [ 60 ]

When by the rout that made the hideous roar,

His goary visage down the stream was sent,

Down the swift Hebrus to the Lesbian shore.

Alas! What boots it with uncessant care

To tend the homely slighted Shepherds trade, [ 65 ]

And strictlymeditate the thankles Muse,

Were it not better don as others use,

To sport withamaryllisin the shade,

Or withthe tangles of Neæra's hair?

Fameis the spur that the clear spirit doth raise [ 70 ]

(That last infirmity of Noble mind)

To scorn delights, and live laborious dayes;

But the fair Guerdonwhen we hope to find,

And think to burst out into suddenblaze,

Comes the blindFurywith th' abhorredshears, [ 75 ]

And slits the thin spun life. But not the praise,

Phœbusrepli'd, and touch'd my trembling ears;

Fame is no plant that grows on mortal soil,

Nor in the glistering foil

Set off to th' world, nor in broad rumour lies, [ 80 ]

But lives and spredsaloftby those pure eyes,

And perfet witnes of all judging Jove;

As he pronounces lastly on each deed,

Of so much fame in Heav'n expect thy meed.

O Fountain Arethuse, and thou honour'd flood, [ 85 ]

Smooth-sliding Mincius, crown'd with vocall reeds,

That strain I heard was of a higher mood:

But now my Oate proceeds,

And listens to the Heraldof the Sea

That came in Neptune's plea, [ 90 ]

He ask'd the Waves, and ask'd the Fellon winds,

What hard mishap hath doom'd this gentleswain?

And question'd every gust of rugged wings

That blows from off each beaked Promontory,

They knew not of his story, [ 95 ]

And sage Hippotadestheir answer brings,

That not a blast was from his dungeon stray'd,

The Ayr was calm, and on the level brine,

Sleek Panopewith all her sisters play'd.

It was that fatall andperfidiousBark[ 100 ]

Built in th' eclipse, and rigg'd with curses dark,

That sunk so low that sacred head of thine.

NextCamus, reverend Sire, wentfootingslow,

His Mantle hairy, and his Bonnet sedge,

inwroughtwith figures dim, and on the edge [ 105 ]

Like to thatsanguineflowerinscrib'd with woe.

Ah! Who hathreft(quothhe) my dearest pledge?

Last came, and last did go,

The Pilotof the Galilean lake,

Two massy Keyes he bore of metals twain, [ 110 ]

(The Golden opes, the Iron shuts amain)

He shook hismiter'd locks, and stern bespake,

How well could I have spar'd for thee young swain,

Anowofsuchas for their bellies sake,

Creep and intrude, and climb into the fold? [ 115 ]

Of other care they little reck'ning make,

Then how to scramble at the shearers feast,

And shove away the worthy bidden guest.

Blind mouthes! that scarce themselves know how to hold

A Sheep-hook, or have learn'd ought els the least [ 120 ]

That to the faithfull Herdmans art belongs!

What recks it them? What need they? They aresped;

And when they list, their lean and flashy songs

Grate on their scrannelPipes of wretched straw,

The hungry Sheep look up, and are not fed, [ 125 ]

But swoln with wind, and the rank mist they draw,

Rotinwardly, and foulcontagionspread:

Besides what the grim Woolfwith privypaw

Daily devoursapace, andnothingsed,

But that two-handed engineat the door, [ 130 ]

Stands ready tosmiteonce, and smite no more.

Return Alpheus, the dread voice is past,

That shrunk thy streams; Return Sicilian Muse,

And call theVales, and bid themhithercast

Their Bels, and Flourets of a thousand hues. [ 135 ]

Ye valleys low where the milde whispers use,

Of shades and wanton winds, and gushing brooks,

On whose fresh lap the swart Starsparely looks,

Throw hither all yourquaintenameld eyes,

That on the green terf suck the honied showres, [ 140 ]

And purple all the ground withvernalflowres.

Bring the rathePrimrose that forsaken dies.

The tufted Crow-toe, and paleJasmine,

The white Pink, and the Pansie freaktwith jeat,

The glowing Violet. [ 145 ]

The Musk-rose, and the well attir'dwoodbine,

With Cowslipswanthat hang the pensive hed,

And every flower that sad embroidery wears:

Bid Amaranthusall his beauty shed,

And Daffadilliesfill their cups with tears, [ 150 ]

Tostrewthe Laureat Herse where Lycid lies.

For so to interpose a little ease,

Let our frail thoughts dally with false surmise.

Ay me! Whilst thee the shores and sounding Seas

Wash far away, where ere thy bones are hurld, [ 155 ]

Whether beyond the stormy Hebrides,

Where thou perhaps under the whelmingtide

Visit'st the bottom of the monstrous world;

Or whether thou to our moistvows deny'd,

Sleep'st by the fable of Bellerusold, [ 160 ]

Where the great vision of the guarded Mount

Looks toward Namancos and Bayona's hold;

Look homewardAngel now, and melt with ruth.

And, O ye Dolphins,waftthe haples youth.

Weep no more, woful Shepherds weep no more, [ 165 ]

For Lycidas your sorrow is not dead,

Sunk though he be beneath the watry floar,

So sinks the day-star in the Ocean bed,

And yet anon repairs his drooping head,

And tricks his beams, and with new-spangled Ore, [ 170 ]

Flames in the forehead of the morning sky:

So Lycidas sunk low, but mountedhigh,

Through the dear might ofhimthat walk'd the waves;

Where other groves, and other streams along,

With Nectar pure his oozy Lock's he laves, [ 175 ]

And hears the unexpressivenuptiall Song,

In the blest Kingdoms meek of joy and love.

There entertain him all the Saints above,

In solemn troops, and sweet Societies

That sing, and singing in their glory move, [ 180 ]

And wipe the tearsfor ever from his eyes.

Now Lycidas the Shepherds weep no more;

Hence forth thou art theGeniusof the shore,

In thy largerecompense, and shalt be good

To all that wander in that perilous flood. [ 185 ]

Thus sang theuncouthSwain to th' Okes and rills,

While the still morn went out with Sandals gray,

He touch'd the tender stops of various Quills,

With eager thought warblinghisDoricklay:

And now the Sun had stretch'd out all the hills, [ 190 ]

And now was dropt into the Western bay;

At last he rose, and twitch'd his Mantle blew:

To morrow to fresh Woods, and Pastures new.

eumendies_利西达斯 -英文注释

Introduction.Background and Text. Lycidas first appeared in a 1638 collection of elegies entitled Justa Edouardo King Naufrago. This collection commemorated the death of Edward King, a collegemate of Milton's at Cambridge who drowned when his ship sank off the coast of Wales in August, 1637. Milton volunteered or was asked to make a contribution to the collection. The present edition follows the copy of Poems of Mr. John Milton(1645) in the Rauner Collection at Dartmouth College known as Hickmott 172. Milton made a few significant revisions to Lycidas after 1638. These revisions are noted as they occur.

Form and Structure. The structure of Lycidas remains somewhat mysterious. J. Martin Evansargues that there are two movements with six sections each that seem to mirror each other. Arthur Barker believes that the body of Lycidas is composed of three movements that run parallel in pattern. That is, each movement begins with an invocation, then explores the conventions of the pastoral, and ends with a conclusion to Milton's "emotional problem" (quoted in Womack).

Voice. Milton'sepigramlabels Lycidas a "monody": a lyrical lament for one voice. But the poem has several voices or personae, including the "uncouth swain" (the main narrator), who is "interrupted" first by Phoebus (Apollo), then Camus (the river Cam, and thus Cambridge University personified), and the "Pilot of the Galilean lake" (St. Peter). Finally, a second narrator appears for only the last eight lines to bring a conclusion in ottava rima (see F. T. Prince). Before the second narrator enters, the poem contains the irregular rhyme and meter characteristic of the Italian canzone form. Canzone is essentially a polyphonic lyrical form, hence creating a serious conflict with the "monody." Milton may have meant "monody" in the sense that the poem should be regarded more as a story told completely by one person as opposed to a chorus. This person wouldpresumablybe the final narrator, who seemingly masks himself as the "uncouth swain." This concept of story-telling ties Lycidas closer to the genre of pastoral elegy.

Genre. Lycidas is a pastoral elegy, a genre initiated by Theocritus, also put to famous use by Virgil and Spenser. Christopher Kendrickasserts that one's reading of Lycidas would be improved by treating the poem anachronistically, that is, as if it was one of the most original pastoral elegies. Also, as already stated, it employs the irregular rhyme and meter of an Italian canzone. Stella Revardsuggests that Lycidas also exhibits the influence of Pindaric odes, especially in its allusions to Orpheus, Alpheus, and Arethusa. The poem's arrangement in verse paragraphs and its introduction of various voices and personae are also features that anticipate epic structures. Like the form, structure, and voice of Lycidas, its genre is deeply complex. James Sitar

Monody.A lyrical lament for one voice.

height.The headnote ― "In this Monody ... height." ― did not appear in 1638 (Justa Edouardo King). This addition might be due to the less strict laws regarding published texts. The Trinity MS has the headnote but without the final sentence: "And by occasion ... height." The clergy Milton refers to is the clergy of the English Church as ruled by William Laud, Archbishop of Canterbury, a champion of traditionalliturgyand the bane of reformistpuritans. Bishops fell out of power in 1642, between the two editions.

Friend.Edward King, aschoolmateof Milton's at Cambridge who drowned when his ship sank off the coast of Wales in August, 1637. King entered Christ's College in 1626 when he was 14 years old. Upon finishing his studies, King was made a Fellow of Christ's thanks to his patron King Charles I. The Trinity MS of Lycidas is dated Nov. 1637, three months after King's death.

Never-sear.Never withered. 1638 has "never-sere". Laurel was considered the emblem of Apollo, myrtle of Venus, and ivy of Bacchus.

Lycidas.The name Lycidas is common in ancient Greek pastorals, establishing the style Milton imitates for this poem. William Collins Wattersonnotes that in Theocritus' pastoral, Lycidas loses a singing competition. Watterson asserts that Milton is aligning King with Lycidas in an attempt to portray himself as victorious over King. Virgil's nintheclogueis spoken in part by the shepherd Lycidas, a scene that includes, as Balachandra Rajanpoints out, a reference to social injustice. Lucan's Civil Wars 3.657-58 also tells the story of a Lycidas pulled to pieces during a sea battle by a grappling hook.

Lycidas?An echo of Virgil; "Who would not sing for Gallus?" (Eclogue 10.5).

bear.Bier, or funeral platform. 1638 has "biere".

Begin then, Sisters.Following the pastoral tradition of Theocritus, Moschus, and Virgil, Milton invokes the muses to begin the lament. See Virgil's Eclogue 4.1. The sisters are thenine muses, daughters of Zeus and Mnemosyne (memory). Their sacred well is called Aganippe on Mount Helicon, just a bit lower than the "seat" of Jove.

lucky.It would certainly be bad luck to refuse an invitation to sing for the dead. Virgil's persona implies as much in Eclogue 10.5-6. See also OED2.

opening.1638 has "glimmering" instead of "opening"; The Trinity MS replaces "glimmering" with "opening".

Batt'ning.Feeding.

Star.Venus asHesperus, the evening star. 1638 has "ev'n-starre" in place of "Star that rose, at Ev'ning,". The Trinity MS corrected the 1638 reading to "Oft till the star that rose in evening bright".

westering.1638 has "burnisht" in place of "westering"; Trinity MS initiated the change to "westering".

th'Oaten Flute.A Panpipe, or the flute used by Pan, traditionally associated with the songs of shepherds. See Virgil's Ecologues10.64-5. Spenser calls him "God of shepheards all" in The Shepheardes Calendar, "December," 7. Drawingof Pan playing a panpipe.

Satyrs.Mythical goat-men renowned for lust. Milton is probably referring to his (and King's) classmates at Christ's. Picture.

Damoetas.A traditional pastoral name, see Virgil's Eclogue 3. Also a clownish shepherd named Damoetas appears in Sidney's Arcadia. Search Dartmouth's Library catalog.Milton might be referring to Christ's College tutor William Chappel.

to hear our song.The narrator imagines that he and King were shepherds (poets and students) in the same pasture (Christ's College, Cambridge) and learned from the same master, William Chappel (perhaps personified here as Old Damoetas).

gadding.Wandering, unruly.

Canker.Cankerworm, a garden pest.

Taint-worm.Intestinal parasite that afflicts youngcalves, that is, weanlings.

weanling.Young livestock, recently weaned from mother's milk.

wardrop.Wardrobe. 1638 has "wardrobe".

blows.Blossoms.

Bards.Ancient Druid poet-singers: "An ancient Celtic order ofminstrel-poets, whose primary function appears to have been to compose and sing (usually to the harp) verses celebrating the achievements of chiefs and warriors, and who committed to verse historical and traditional facts, religious precepts, laws, genealogies, etc." (OED2).

Mona.Anglesey, an Island off the west coast of Britain, once the home of Celtic druids.

Deva.The river Dee, where Chester, King's destination, stands. Spenser's Faerie Queene 4.11.39 refers to the Dee as "divine."

fondly.Foolishly, idly.

Lesbian shore.Calliope, daughter of Jupiter and Mnemosyne was Orpheus's mother and a muse. Orpheus, according to legend, could charm animals, birds, and even inanimate bits of nature with his music. For Milton, as for many others, he serves as a personified symbol of the power of poetic song. For the story of the death of Orpheus, see Ovid's Metamorphoses 11.1-66. Also see Albrecht Dürer's 1494 engraving, Death of Orpheus.

strictly.1638 misprints this as "stridly".

Or with.1638 has "Hid in the" in place of "Or with". "Or with" is a Trinity MS correction.

Amaryllis.The names of the nymphs, Amaryllis andNeaera, are conventional, borrowed from Virgil's Eclogues 1.4-5and Eclogues 3.3.

Guerdon.Reward.

Fury.Milton refers to fate or destiny here as a "Fury," as if one of the Eumendies from classical Greek drama. Some traditionspersonifythe Fates as three sisters, the sisters of destiny; one spins the thread of life, one measures out its length, and the thirdsnipsit with shears. Hughes asserts that this figure is Atropos. See Plato's Republic 620e.

Phoebus.Apollo. Virgil, in Eclogues 6.5-6,imagines the "Cynthian god" plucking at his ear.

foil.Hughesnotes that a foil is the "setting of a gem".

Arethuse.A fountain in Sicily associated with poetic inspiration (see Arcades 30-31). Mincius is the river of Virgil's hometown, Mantua. Virgil associates the Mincius with his own pastoral verse in Eclogues 7. 15-16 and Georgics 3. 20-21.

higher mood.Epic poetry was considered to be a more elevated form than pastoral, thus in a higher mode.

Herald.Triton, a sea-god usually pictured with a trumpet.

plea.That is, at Neptune's request, to testify in his defence.

swain.A shepherd; a word frequently used by Theocritus, Virgil, and Spenser.

Hippotades.Homericepithetfor Aeolus, the wind-god, son of Hippotas. See Odyssey 10.3.

Panope.A sea nymph.

Bark.Small ship.

th'eclipse.A ship built during an eclipse might be imagined to be either cursed with bad luck or simply ill-built as a result.

Camus.Personification of the river Cam, which runs through Cambridge. This personification draws comparisons to Virgil's personification of Mincius, the river that runs through his home town.

sanquine flower.The Hyacinth. Apollo made this flower from the blood of his beloved Hyacinthus, whom he accidentally killed. The story is in Ovid's Metamorphoses 10.214-16.

The Pilot.It is commonly accepted that this refers to St. Peter, to whom Christ gave "the keys of the kingdom of heaven" (Matthew 16:19). Peter's first meeting with Jesus is told in Luke 5:2-4.

Miter'd.A miter is a liturgical headress worn by bishops.

Line 113.1645 has a period at the end of this line, but that appears to be an error, especially since the line is the last on the page in 1645.

Anow.Enough. 1638 has "Enough".

into the fold.See John 10:1.

Blind mouthes!John Ruskin suggests that "a bishop means a person who sees" and a "pastor means one who feeds. The most unbishoply character...is therefore to be blind. The most unpastoral is, instead of feeding, to want to be fed,―to be a mouth" (quoted in Orgel and Goldberg).

scrannel.Thin, shriveled.

Lines 121-127. An echo of Menalcas' sentiments in Virgil's Ecologues 3.81, 4-9, 30-4.

Woolf.The Roman Catholic Church.

privy.Secret. See 2 Peter 2:1. Perhaps also a pun on the Privy Council.

nothing.Critics dispute whether "little" should stand. In accordance with 1645, most modern editions use "nothing."

sed.1638 has "said".

two-handed engine.The meaning of this phrase has generated much commentary. Orgel's assertion, that it is a sword large enough to require two hands to use, is commonly accepted.

smite once, and smite no more.See Matthew 26:31 and Mark 14: 27-9.

Alpheus.Personification of a river in Greece and also the god who fell in love with Arethusa and pursued her until she was turned into a fountain. See Ovid's Metamorphoses 5.865-875.

swart Star.Sirius, the dog star, isascendantduring the hottest days of the year; hence the term, "dog days."

rathe.Ready to bloom.

Crow-toe.Wild hyacinth.

Gessamine.Jasmine, a climbing shrub with fragrant flowers.

freakt.Flecked or streaked whimsically or capriciously;variegated. See OED2. "Freakt with jeat" (jet, black) means flecked with black streaks or spots.

wan.Pale.

Amaranthus.In the garden of Eden, an immortal flower (Paradise Lost 3.353-57). See also Spenser's Faerie Queene 3.6.45 (search "Amaranthus").

Daffadillies.This flower list, a typical pastoral element, was first added to the Trinity MS on a separate sheet of paper and marked for insertion here. Sackscontrasts this section with the plucking at the beginning of the poem (line 3). He asserts, "the anger has been purged, and the rewards (the undying flowers of praise) have been established."

Hebrides.The Hebrides lie off the west coast of Scotland.

whelming.Overwhelming, or drowning. 1638 has "humming". Trinity MS also has "humming", changed to "whelming" by marginal hand in BM and Cambridge copies of Justa Eduardo King (Carey & Fowler).

moist.Tear-dampened.

Bellerus.A giant for whom Land's End was called Bellerium in Roman times.

guarded Mount.Mount St. Michael's, near Land's End on the Cornish coast, across the Channel from Mont St. Michel. Milton imagines the patron saint of England looking out from here to guard England from overseas (Catholic) religion. Namancos is in Spain and Bayona a fortress near Cape Finisterre.

Look homeward.The Angel could refer to either St. Michael, whose mount it is, or Lycidas. In either case, theinjunctionis for him to turn his eye from the threat of Spain (represented by Namancos and Bayona) and instead to look homeward, where Lycidas has drowned (Orgel & Goldberg). Lawrence Lipkingasserts that the angel is in fact Lycidas, who is looking not to where he drowned but to his destination, Ireland. He further asserts that Milton demands a change of attention from Spain to Ireland because he felt the pagans in Ireland were a serious threat to England.

Dolphins.Dolphins were thought by sailors to be a good omen at sea, looking after the ship and guarding it from peril.

him that walk'd the waves.Alluding to Jesus, who walked on water according to Matthew 14:25-26.

weep no more.Recalls the opening line of the poem "Yet once more, O ye Laurels, and once more." The invocation to begin the lament is repeated as the invitation to end the lament.

unexpressive nuptial Song.According to Hughes, "the unutterable nuptial Song is sung at the marriage supper of the Lamb." See Revelation 14:9. Janet E. Halley makes important points about theunacknowledgedhomoerotic features of Milton's pastoral heaven here and in Epitaphium Damonis (see her "Female Autonomy"241-242).

In the blest Kingdoms meek of joy and love.1638 omits this line entirely.

wipe the tears.See Revelation 7:17.

Genius.The spirit or guardian angel of the place.

Dorick.The sort of Greek spoken in Crete and Laconia. Also the dialect preferred by Theocritus and Bion, the earliest practictioners of pastoral verse. A doric lay is the sort of song sung by pastoral poets in doric.

th'Okes and rills."Oates," reeds, quills, and pipes are all terms associated with composing and singing pastoral poetry. This line signifies the end of the shepherd persona.

Quills.The hollow reeds of the shepherd's pipes; the stops are the holes one covers with fingers to make different notes sound.

Pastures new.See the end of Virgil's Eclogues10. 70-97.

爱华网

爱华网