原文在这里:(需科学上网)并已附在文末。

我的回答是二手自 的内容

对评论区的几点回应:

1. 为什么双方要为了十亿美金放弃潜在的所有Soft Money?在巴菲特的原文中已经提到了,2000年总的软钱是360M, 一方就是180M,1B=1000M相当于5~6次竞选所需要的全部金额,在有折现的情况下这笔钱足以超出潜在的软钱收益。

2. 关于许多进一步讨论,主要还是说,这个例子只是作为一个模型。共和党民主党的议员数目也好,是否串通也好,咱们现在不考虑这些,因为首先就不可能有这样古怪的亿万富翁吧。

实际上,巴菲特此文的本义并不是介绍亿万富翁如何影响政治——相反,他只是借一个非常诡异的例子(这个Eccentric Billionaire)来说明,不应当让金钱影响选举,选举应当坚持其本来的原则,正如他在一开始就说的,他长期以来都在发现被低估的股票,而不是去获取政治影响力。

-----------------------

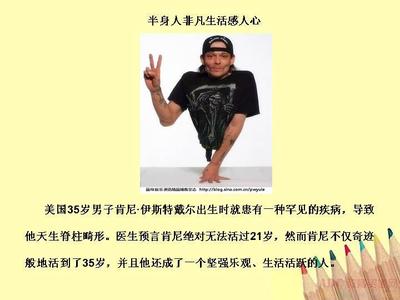

今年,亿万富翁Donald Trump宣布竞选总统。坐拥九十亿美元身价的川普宣称自己很有钱,因而竞选资金完全不需要依靠捐赠(尽管实际上他还是募捐了不少钱),因而可以避免以往总统和政党受到经济力量把持的状况。

然而,亿万富翁想要影响政党的决策,并不是一定要通过捐钱的方式。聪明的亿万富翁可以不花一分钱达到自己的目的,他要做的只是利用一下囚徒困境。

政党在议会斗争中,不可避免地需要大量的资金支援。这种资金被分为硬钱(Hard money)和软钱(Soft money)。硬钱的捐赠是收到联邦选举委员会的严格监控的,这些钱被用于“Political Campaign”即政治宣传活动;软钱则不受监控,但这些钱只能用于“Party Building”政党建设。两者的区别有些微妙,不过反正是政党所需要的资金,自然是多多益善。由于硬钱的额度收到限制,软钱成为各政党募捐的更重要来源,其额度也一再上扬。

2000年,美国国内又掀起了一波提议禁止软钱或加强对软钱监管的呼声。假定现在有一个法案(Bill)计划禁止软钱,而且这个法案即将进入国会进行最终投票。对于两个政党来说,显然禁止软钱是要他们的命,可以想见相当一部分议员将会投反对票。那么,亿万富翁是否能够在这里插上手呢?

另一位远比川普著名的亿万富翁Warren Buffett(沃伦·巴菲特),在《纽约时报》上刊登了一片假想这种场景的文章,名为《The Billionaire's Buyout Plan(亿万富翁的买断计划)》,其中写道:

Suppose some eccentric billionaire(not me, not me!) makes the following offer. If the bill is defeated, this E.B. will donate $1Billion in soft money to the party that delivers the most votes to getting the reform passed.

假定有一个古怪的亿万富翁(不是说我,不是说我!)做出了如下的承诺:如果法案没有通过,这位古怪的亿万富翁将会捐赠十亿美元给投出更多支持票的政党。

简便起见,我们假定国会里只有一个民主党议员和一个共和党议员,再假定需要两人都支持才能通过法案,这样就构成了一个博弈,其支付矩阵如下图所示:

我们可以看到,这其实是一个经典的囚徒困境博弈:我们可以看到,这其实是一个经典的囚徒困境博弈:

对于民主党议员来说:

1. 如果共和党议员选“支持”:

1)如果自己选择“反对”,法案无法通过,共和党获得十亿美元,自己一分钱没有,结果是比对方少了十亿美金;

2)如果自己选择“支持”,法案通过,双方都没有拿到钱,也都无法再获得软钱,双方打了个平手;

综合1)2),应该选择“支持”。

2. 如果共和党议员选择“反对”:

1)如果自己选择“反对”,法案无法通过,什么都不变,平手。

2)如果自己选择“支持”,法案还是无法通过,还能多拿十亿美金。

综合1)2),应该选择“支持”

所以无论共和党议员选什么,民主党议员都应该选“支持”,这被称为“占优策略(Dominant Startegy)”。同理,共和党议员也应选择“支持”,最后我们得到了一个纳什均衡:均选择“支持”。

但是,从图上就可以看出:均选择“支持”并不是最优解,最优解应该是均选择“反对”。法案通过了,双方虽然表面都没拿到那十亿打了个平手,但是双方都没得拿软钱了,比原来的处境更加糟糕。

更加气人的是,因为法案通过了,那位古怪的亿万富翁按照约定,也不需要付那十亿美元。

这才是经济力量控制政治的真谛啊~

-------------------以下是原文----------------

For five decades, I've looked for undervalued stocks. But if I'd been interested in the biggest bargain around, which I wasn't, I would have bought political influence. For many a year, it was far cheaper than anything to be found in the stock market. A relatively modest contribution -- say, $25,000 -- was enough to make the donor a V.I.P. in the political world. And really big amounts? As a fund-raising senator once jokingly said to me, ''Warren, contribute $10 million and you can get the colors of the American flag changed.''

Markets correct, though. Politicians began exploiting the soft money loophole, and pricing became more efficient. Soft money contributions jumped from $86 million in the 1992 election cycle to an expected $360 million in the current one. That's a growth rate worthy of Silicon Valley: 20 percent annually.

And the game has barely started. For most supplicants, cost still lags ridiculously far behind value. American business spends $200 billion a year on advertising to influence consumers. In many industries -- communications, tobacco, banking, pharmaceuticals and insurance among them -- political influence can sometimes be of similar commercial importance. It also matters critically to such professionals as lawyers, doctors, and teachers. Absent reform, these interest groups will continue to ante up for political influence, accepting the soaring prices that the vendors demand.

These vendors, however, maintain that it's all O.K. They argue that a contribution may buy access and empathy but are shocked -- shocked! -- at the thought that it could influence their vote.

Perhaps. But let me suggest a fanciful thought experiment to test their position. Suppose that a reform bill is introduced, raising the limit on individual contributions to federal candidates from $1,000 to, say, $5,000 but prohibiting contributions from all other sources, among them corporations and unions. These entities could still encourage their employees, stockholders, or members to contribute personally, but could do no more -- a ban, incidentally, that applied to them until the ''soft money'' dodge was introduced in 1978. Such a bill would be far from a panacea for all campaign finance ills, of course, but it would at least be a start.

Why should this bill stand a chance in a Congress enraptured with the status quo? Well, just suppose some eccentric billionaire (not me, not me!) made the following offer: If the bill was defeated, this person -- the E.B. -- would donate $1 billion in an allowable manner (soft money makes all possible) to the political party that had delivered the most votes to getting it passed. Given this diabolical application of game theory, the bill would sail through Congress and thus cost our E.B. nothing (establishing him as not so eccentric after all).

The beauty of this plan is that it would highlight the absurdity of claims that money doesn't influence Congressional votes. What a $1 billion promise would buy here is a ''counter-revelation'' among legislators, who'd be induced by the offer to shift their position on campaign finance by 180 degrees so as to prevent the money from being delivered to the opposition party. When the roll call began, Republicans and Democrats alike would, in this scenario, suddenly find merit in a reform that they had previously classified as somewhere between repulsive and un-American.

This hypothetical exercise, it should be noted, does not expose the legislators who now oppose reform as evil or corrupt -- but only as human. How many of us push for laws that are clearly injurious to our self-interest? I can assure you that I've never looked for ways to make retention of my job less secure. Why should legislators?

Would a system that allows an E.B. to influence legislation by a $1 billion promise make sense? Of course not. And neither does a system that allows an anything-but-eccentric individual, corporation or union to achieve similar influence by a large check. Only individuals vote -- and then just once per election. Let only individuals contribute -- with sensible limits per election. Otherwise, we are well on our way to ensuring that a government of the moneyed, by the moneyed, and for the moneyed shall not perish from the earth.

Drawing

Warren E. Buffett is chairman of Berkshire Hathaway Inc.

1/3 1 2 3 下一页 尾页

爱华网

爱华网